In Search of the Guaycura and Pericú Indians: Rock Art in the Cape Region

By Bryan Jáuregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures

This article was originally published in Janice Kinne’s Journal del Pacifico.

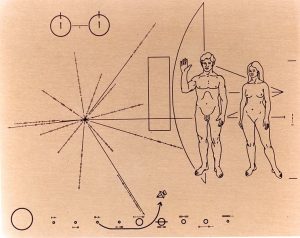

Pioneer 11 Pictograph

In 1972 when the Pioneer 11 spacecraft was sent to explore the outer solar system, it was outfitted with a pair of gold-anodized aluminum plaques featuring pictographs designed to explain to any intercepting extraterrestrials about humans, hydrogen and the earthly origins of the spacecraft. The human figures are clear enough but seriously, to the uninitiated eye everything else in the picture looks like nothing more than a bunch of circles and lines.

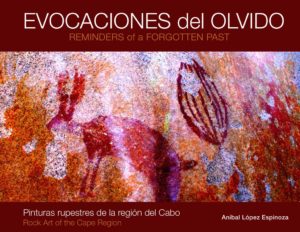

So when you take a walk in southern Baja with anthropologist Aníbal López to view some of the pictographs he’s documented for his forthcoming book, Reminders of a Forgotten Past: Rock Art of the Cape Region, and in amongst the deer, rabbits and fish you see a series of circles and lines left there maybe 1000 years ago by the now-extinct Guaycura or Pericú Indians, you can’t help but wonder who these people really were, and what their images would say to an informed observer.

Searching for clues to these mysteries has been Aníbal’s quest since he was 7 years old. “My family had the concession to farm scallops in Bahia Concepcion near Loreto, and I would often accompany my dad on long road trips to different villages. I hated it. But my dad loved natural history and one day he took me to a canyon filled with petroglyphs made by the Guaycura Indians. It changed everything for me. From then on the long road trips became my dreamscape, and I would spend them imagining Indian life and what it must have been like to be a part of these semi-nomadic communities in such inhospitable terrain. I’m still doing essentially the same thing, only now I’m the one walking the tough terrain.”

Most of the sites that Aníbal has documented – there are 11 in the book but he’s documented nearly 300 in the Cape Region of Baja California Sur (BCS) so far – are found in or around mountain ranges near Rancherias, or temporary Indian settlements that were visited on a seasonal or ceremonial schedule. In modern times this means that they are mainly located on private ranches, so Aníbal has spent countless hours cultivating relationships with area ranchers, most of whom are keen to help but maybe a little fuzzy on the logistical details; it is not unusual for Aníbal to spend three to six days on a ranch hunting for a single site that a rancher remembers seeing as a boy.

Photo by Anibal Lopez

But when he finds the site often what the Indians recorded about their lives on large granite boulders can send his imagination straight back into childhood overdrive. “Being deep in the mountains and coming across ochre paintings of fish and sea turtles is really incredible. Clearly these pre-Hispanic peoples were adept at living in both coastal and mountainous environments. They must have had strong skill sets for both places.” Hamuri Fujita, head of the Institute for Anthropology and History (INAH) in BCS adds “The lack of housing sites and archaeological materials at these sites leads us to think that the people who made these rock art paintings moved easily between the Sierras and the coast, often or seasonally, depending on the ceremonies or festivities planned.”

The first people to discover the pictographs were the Jesuit missionaries, who took a decidedly dim view of the locals. “Stupid, awkward, rude, unclean, insolent, ungrateful, mendacious, thievish, abominably lazy….” were the attributes recorded by Jesuit Johann Baegert.

Maybe. But they sure knew how to sail. Unlike their counterparts in the Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico and the southern Pacific coasts of North America, the Baja California Sur Indians were skilled raft makers and sailors, and traveled easily between the mainland and the islands, carrying people and information. Their great fishing and turtle hunting prowess was well-documented by observers throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. But how long ago did they develop these skills? New archaeological evidence indicates that Pericú skulls strongly resemble those of aborigines native to Polynesia and Asia, and many researchers now believe that the Pericú reached Baja California Sur by navigating from island to island in their canoes.

Photo by Anibal Lopez

So if the circles and lines on the Pioneer 11 pictographs were used to represent the hyperfine transition of hydrogen, the binary digit 1 and the solar system, then perhaps the circles and lines in the pictographs of the pre-missionary, pre-Hispanic Indians of BCS were depictions of their original home and its relationship to Baja, or maybe navigational charts to find their way back, or perhaps just the best way to cook dorado over a mesquite fire. These things may be forever unknowable, but thanks to Aníbal’s 6 long years of self-funded work in finding and documenting these sites, we can now be like the extraterrestrials envisioned by the Pioneer 11 pictograph crew: aware now of another race of beings, and free to let our imaginations soar about what their messages might mean.

Cover of Anibal’s Book

Todos Santos Eco Adventures has teamed up with Aníbal to take visitors to one of the Guaycura rock art sites documented in his book that is still not open to the general public. Located on a lovely old working ranch along the former Camino de las Misiones, this walk features not only rock art, but other evidence of the Guaycura civilization including grinders, mortars and even some arrowheads. There is about 90 minutes of moderate walking over uneven, rocky terrain that features gentle up and downhill gradients. While at the site you’ll be helping Aníbal collect vital information for the federal registration process to promote future preservation of these unique sites. Funds go directly to supporting the Aníbal’s work. Aníbal’s book is scheduled to be published in September 2013.