By Bryan Jáuregui based on research by Dr. Shane Macfarlan. This article first appeared in Janice Kinne’s Journal del Pacifico.

He really was just a good Catholic boy trying to make the padres proud, but suspicion and cruelty transformed him into something they foolishly feared he was all along, the vicious leader of a rebellion.

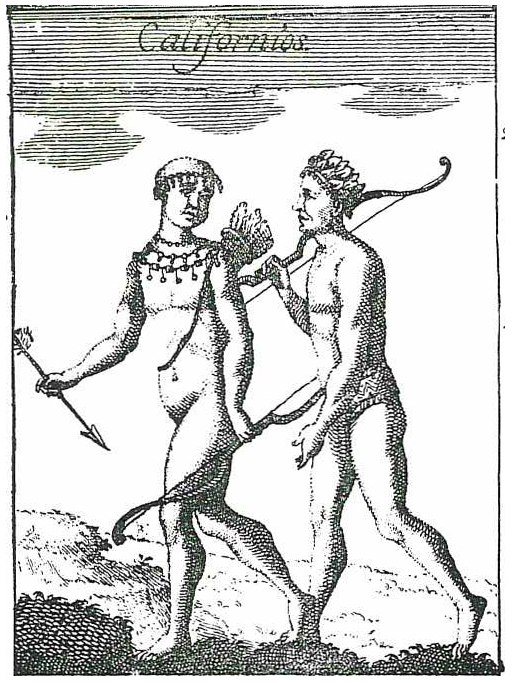

It was 1734 in Baja California Sur and the indigenous Pericue and Guaycura peoples had dropped their grievances with each other to join forces against their common enemy, the Jesuits. Promises of eternal salvation did nothing to alter the Indians’ view that the byproducts of Jesuit rule – physical decimation by measles and smallpox and cultural devastation by Christianity and monogamy – were assaults that demanded a resolution in the here and now. But the Jesuits, who had been the ruling arm of the Spanish crown in Baja since 1697, did have some faithful converts among the native peoples. Among them was a young Pericue named Fabian, a member of the Todos Santos mission. Dr. Shane Macfarlan, professor of Anthropology at the University of Utah, has painstakingly pieced together some key elements of Fabian’s life and this account is based on his research.

When the Indigenous Rebellion broke over the Jesuits with the bludgeoning deaths of Padre Tamaral in San Jose del Cabo and Padre Carranco in Santiago in October 1734, Fabian firmly sided with the Jesuits against the rebels, many of whom were Pericue like himself. He left behind his family and traveled with the founder of the Todos Santos mission, Padre Taraval, throughout the southern part of the peninsula to understand the full nature and extent of the rebellion. He worked with the Spanish military in 1735 during the retaking of La Paz and the reconnaissance of the south, and again in 1736 to locate rebels and gather more intelligence. The Indian rebels were stunned by Fabian’s fealty to the Jesuits. They attempted to lure him to the rebel side with promises of earthly gifts and rewards. When that failed they threatened to kill his family. Nothing worked and Fabian remained steadfast in his loyalty to the Jesuits. Noted Padre Taraval, “Nothing could move him; nor did all of this prevent him from talking to them, entreating them, and even upbraiding them for their ungrateful apostasy and misconduct.” (Wilbur, 1931)

By 1734 the indigenous rebels weren’t the only ones taking an unkind view of the Jesuits in Baja. The Spanish rulers of the rest of Mexico, and by extension the crown, strongly suspected that the Jesuits were harboring hordes of gold, silver and pearls in Baja that they were not sharing with the king. When the anti-Jesuit Spanish viceroy of Mexico sent the governor of Sinaloa, Huidobro, to quell the indigenous revolt, he urged leniency. Jesuit historian Father Peter Dunne notes, “For the tranquility and pacification of the uprising there was given to the governor of Sinaloa a commission to proceed against the rebels with propriety…but without offensive warfare.” Accordingly, Huidobro sought to pacify the rebels with gifts of food, clothing, tobacco and full pardons. For their part, the native groups who remained loyal to the Jesuits and the Spanish crown couldn’t win for losing. They were despised by their own people, yet their allegiance to the Jesuits and to the crown, which they were forced to demonstrate by working to the point of exhaustion each day, was regarded with great suspicion by both the Jesuits and the Spanish soldiers who considered many of them rebel spies.

By Padre Taraval’s own account, Fabian proved himself loyal to the Jesuits at every turn, even attempting to convert the rebels who threatened his family. But this allegiance did not afford him sufficient protection and Spanish soldiers attacked his wife. While the record is not clear, this attack likely involved sexual assault and when Fabian tried to intervene, he was forcibly restrained by the soldiers. It was this extreme provocation that caused Fabian, the most devoted of indigenous converts at the Todos Santos mission, to become the thing the soldiers had suspected he was all along – a rebel leader. Even though the Jesuits had already retaken the Cape region and reoccupied the Todos Santos mission by this time, Fabian put together a small contingent and planned an attack. But the plot was soon discovered and Fabian gave himself up so his compatriots could escape. While he had lived most of his life as a loyal friend to the Jesuits, his brief stint as a rebel lead rapidly to his trial, conviction and execution. Padre Taraval noted with some satisfaction that, like the true Catholic he was trained to be, Fabian repented on his way to the gallows.

This brief account of Fabian’s life is one of the few stories of an individual indigenous person on the Baja peninsula that is part of the written historical record. The few others mentioned by name in connection with the native uprising – Domingo Botón, Chicori, and Bruno – were all described as being of mixed race, a fate of birth that the Jesuits saw as a factor in the rebellion. Notes Jesuit Father Peter Dunne in his 1952 book, Black Robes in Lower California, “There was a mixture of breeds in the south: mulattoes, the offspring of Negroes dropped off here by the Manila galleons, and mixtures of white blood from the English and Dutch freebooters who had long known these coasts….A mixture of bloods probably explains the aggressive malice of some of the (natives), especially…of the leaders of the revolt.” Climate was also considered a factor. Continues Dunne, “Doubtless climate had something to do with the disparity in the quality of the southerners…A climate with no prolonged cold or vigorous winter often seems to dissipate the energies of men and sometimes even their virtue.” In other words, the Jesuits grasped at straws when trying to explain the revolt when in fact the reasons were remarkably clear. At the time the rebellion started, raging epidemics of measles and smallpox had decimated the Guaycura and Pericue populations, reducing their populations by half in a single generation. Moreover, just a year before the rebellion started the Jesuits had launched a campaign to eradicate polygamy among the native population. In all the Indian groups of the Baja peninsula women were the chief procurers of food, so the more wives a man had the higher his status, and important men like chiefs and shamans had several. In a direct challenge to local leaders, the Jesuits made explicit efforts to recruit young women as neophytes. It was these twin assaults upon health and culture that united the once warring factions of the southern Baja Indians against the Jesuits. It was a fight in which both sides won some battles and both sides lost the war. The Spanish crown expelled the Jesuits from the Baja peninsula in 1768, but by the time their enemies were vanquished, the Guaycura and Pericue Indians were essentially living ghosts, by and large culturally extinct. No more padres, no one left to convert. But the peninsula did retain its sense of independence, and the ranchero culture that followed that of the indigenous people definitely retains some of that spirit of rebellion that was sparked, however belatedly, in a Todos Santos Pericue name Fabian.