by Sergio and Bryan Jauregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures

June through November are the best months for diving and exploring the Sea of Cortés – “the aquarium of the world” – as the warmer water temperatures mean an (even more) incredible variety of fish, superior visibility and calmer seas. But a word of warning for those of you who do venture to the depths of the Sea of Cortés: there is one truly scary thing that you should know about – and be constantly on the alert for – and that is El Mechudo. There are many variations on the story of this wild-haired free diver, but this is the one that the old fishermen around Punta Mechudo tell…

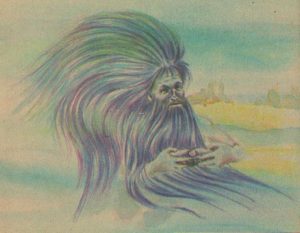

Long ago, when La Paz was the pearl capital of the world, there lived a Yaqui Indian known as El Mechudo, The Hairy One. In those days there were many pearl divers of great skill and daring in La Paz, men and women who could hold their breath for long stretches at a time and knew the secrets of finding large and magnificent pearls. Each year the companies that sold La Paz pearls around the world would hold a contest to see which diver could find the largest and loveliest pearl. The diver who won was awarded the great honor of having his or her pearl presented to the Virgin of Guadalupe. For as many years as anyone could remember, El Mechudo, with his wild flowing black hair, had won the contest; he could hold his breath longer and dive deeper than any of the other divers and he always knew where to find the most fantastic pearls.

Then one year El Mechudo failed to appear at the beginning of the contest. They waited for him for several hours but finally had to hold the event without him. By the time El Mechudo arrived to compete, the contest was over and a winner had been declared. Enraged, El Mechudo insisted on diving. His friends begged him not to risk his life and to simply wait until the following year to prove himself the champion once again. The organizers warned that even if he found the biggest, blackest pearl of all time that they would not crown him the winner, nor would they present the pearl to the Virgin. Unfazed, El Mechudo dove into the water. Time passed. After many minutes he still had not returned to the surface. His friends jumped into the water to search for him and saw a sight that would haunt them for the rest of their lives: the lifeless body of El Mechudo with his hand caught in a giant oyster.

The man known as El Mechudo is dead, but he is not gone. To this day divers, kayakers, fishermen and snorkelers in the Bay of La Paz are visited by the ghost of El Mechudo. There are regular reports of unexplainable touches in the night, rearranged camp sites and voices in the wind. And aspiring pearl divers should beware. Word is that if you go into the Bay of La Paz looking for pearls, El Mechudo will find you and offer you the largest, blackest pearl you can imagine. If you accept, your final resting ground will be the depths of the Bay of La Paz, right beside El Mechudo.

So how did La Paz become the Pearl Capital of the World in

the days of El Mechudo? Tony Burton of MexConnect* explored that story by reaching back to the early 1530s when the explorers of Hernán Cortés sailed into the Sea of Cortés searching for the earthly Paradise of California. The first peoples they encountered on the Baja Peninsula were Pericú Indians. The Spanish explorers were immediately struck by the Pericú’s necklaces which were strung with berries, shells and blackened pearls. As the Pericú did not have metal knives they had been retrieving pearls by throwing oyster shells into a fire, charring the pearls in the process. The Spanish explorers soon determined that opening the oyster shells with their knives gave them access to lustrous, milky-white pearls on par with those to be found in Asia or the Middle East. A robust pearl industry was born, and thousands of pearls were sent from Baja to Europe where they were used in the royal regalía of many European courts. While the Jesuits tried to restrict pearl collection during the period of their missions in Baja (1697 to 1768) due to the poor conditions inflicted in the native Indian divers (see story of El Mechudo above), traffic in the pearls persisted. It was estimated that by 1857, 95,000 tons of oysters, that yielded about 2,770 pounds of pearls, had been removed from the Sea of Cortés. The coves around La Paz and Isla Espiritu Santo were the center of the Baja pearl industry.

Pearl diving was revolutionized after 1874 when larger vessels, equipped with diving suits and accompanying equipment, first entered Mexican waters. The new equipment lengthened the season to include the cooler winter months and had the added benefit of reducing shark attacks. But new dangers emerged: divers confined to diving suits for hours at a time frequently suffered rheumatism, paralysis (due to compression and sudden temperature changes) and partial deafness. Equipment failure led to many deaths. (Never fear new divers – Jacques Cousteau radically enhanced the functionality and safety of scuba gear and since his first Aqua-Lung in 1943, equipment safety has increased dramatically.) Despite the problems faced by the divers, by 1889, a La Paz-based pearl company had come to completely dominate the world pearling industry. A 400-grain pearl, found in the shores of Mulege, now forms part of the Spanish crown jewels.

A 1903 article in The New York Times says that the Baja pearl industry had produced more than two million dollars worth of pearls in 1902, including some of the “finest jewels of this kind found anywhere in the world”. The article emphasizes that the area is “noted for its fancy pearls – that is to say, the colored and especially the black ones”. But by 1936 the natural oyster stocks had been depleted past the point of recovery. This depletion, combined with the widespread availaility of relatively inexpensive cultured and artificial pearls, led to the demise of the natural pearl industry in Baja. Today very few natural pearls are harvested in the Sea of Cortés, but several Baja California firms do cultivate pearls. So La Paz, once the center of the world’s pearling industry, is still known today as the “Pearl of the Sea of Cortés”. But remember, should you encounter one of those few remaining natural pearls while diving in the Bay of La Paz and decide to take it home, El Mechudo will make sure grabbing that pearl is the last thing you ever do!

*Much of the information on the pearl industry in La Paz presented here was researched by Tony Burton and presented in his Did You Know column for MexConnect in June 2008. His sources include:

Anon. Important Pearl Fisheries on the Coast of California. The New York Times, June 14, 1903.

Hardy, R. W. H. 1829 Travels in the Interior of Mexico in 1825, 1826, 1827 and 1828. London: Henry Colburn & Richard Bentley. Reprinted in 1977, Texas: Rio Grande Classics.

Kunz, G. F., and Stevenson, C. H. The Book of the Pearl: Its History, Art, Science and Industry.Dover. 2001.

Mayo, C. M. Miraculous Air: Journey of a Thousand Miles through Baja California, the Other Mexico.Milkweed Editions. 2007.