Las Guardianas del Conchalito

It was 2010 and El Manglito had a reputation as one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in La Paz. Outsiders perceived it as a place where trouble thrived. Taxis often refused to enter. “When we decided to set up our office there, I really thought it was a crazy idea” recalls Liliana Gutierrez, the former program director for Noroeste Sustentable (NOS) in Baja California Sur. “NOS director Alejandro Robles stood in the middle of this maligned place and talked about building a sustainability demonstration center so that people could really see what sustainability could look like in La Paz. Sam Walton wanted to have organic gardens and fisheries restoration projects. He wanted to bring in experts from all over the world to meet the fishermen. Really smart people shared this vision with them, and all I could think is that all these people are completely crazy.” As it turns out, she was right. Continues Liliana, “They were crazy. They were crazy in the most needed way that we need crazy people in the world because from that moment began an amazing story.” And everything they envisioned has come to pass. But that was only once the women got involved.

“Our first communication from the fishermen in El Manglito was a rock through the window of our offices” recalls Liliana. Like the rest of their neighborhood, the fishermen of El Manglito had a particularly bad reputation and were infamous for illegally poaching fish in the protected waters around Isla Espiritu Santo. NOS was part of an Espiritu Santo surveillance alliance that had been literally chasing them in boats in an attempt to restrict their nocturnal thievery, so the rock was not a total surprise. “It was a time of high polarization” notes Liliana with a nod to understatement. “Conservation NGOs like NOS had very strong ideas against the fishermen and the fishermen against the NGOs.”

NOS adapted its thinking. They started reaching out to the fishermen through their children by supporting local soccer teams and eventually the fishermen agreed to meet with them. “When we first went into El Manglito we thought we knew everything about fisheries conservation and all we had to do was convince the fishermen” recalls Liliana. “But we soon realized our approach was not working so we started talking in a very different way. And by that I mean we, NOS, stopped talking. We started listening. And it was beautiful how the whole idea of restoration emerged from them.”

NOS adapted its thinking. They started reaching out to the fishermen through their children by supporting local soccer teams and eventually the fishermen agreed to meet with them. “When we first went into El Manglito we thought we knew everything about fisheries conservation and all we had to do was convince the fishermen” recalls Liliana. “But we soon realized our approach was not working so we started talking in a very different way. And by that I mean we, NOS, stopped talking. We started listening. And it was beautiful how the whole idea of restoration emerged from them.”

Many of the fishing families of El Manglito are descended from the Yaqui Indians who left Sonora at the turn of the last century to escape government persecution. The Yaquis are renowned freedivers and used these skills in La Paz to fish for the huge scallops called callo de hacha in the Ensenada de La Paz, a lagoon inside the Bay of La Paz whose shores reach El Manglito. But by 2008 their lagoon was dead and their callo de hachas with it. Raw sewage from the city was being pumped in, and tons of the city’s garbage was being picked up by hurricanes and dumped there. The fishermen therefore started going to the rich waters around Isla Espiritu Santo to fish. But in 2010 the Espiritu Santo Archipelago was declared a marine national park, and the fishermen of El Manglito were transformed overnight from legal actors into illegal poachers. They had not been consulted on the process.

But they were resilient. “The fishermen knew it was possible to bring the callo de hacha back, to restore their original fishing area” says Liliana. “We didn’t know it, but they did.” The fishermen knew where the richest points in the bay were for the scallops and knew what needed to be done. “We had assumed that they were evil fishermen and that we were going to save them. Turns out, they knew exactly how to save themselves.” Thus started the callo de hacha restoration project that took seven years and attracted people from all around the world – biologists, conservationists, impact investors. “Everything was happening as Alejandro and that team had dreamed. It was beautiful.”

But they were resilient. “The fishermen knew it was possible to bring the callo de hacha back, to restore their original fishing area” says Liliana. “We didn’t know it, but they did.” The fishermen knew where the richest points in the bay were for the scallops and knew what needed to be done. “We had assumed that they were evil fishermen and that we were going to save them. Turns out, they knew exactly how to save themselves.” Thus started the callo de hacha restoration project that took seven years and attracted people from all around the world – biologists, conservationists, impact investors. “Everything was happening as Alejandro and that team had dreamed. It was beautiful.”

But only once the women showed up. NOS, with the support of key funders, had made the controversial decision to pay the fishermen during the restoration period while fishing was suspended. Some of their wives were not impressed with the results. Martha Garcia, speaking for herself and her friend Araceli Méndez says, “As soon as our husbands started receiving payment for not fishing during the restoration, our dream of transforming El Manglito into a beautiful, healthy community became just a job for them. They lost the dream.” Araceli didn’t think their husbands were performing particularly well at the job either. El Manglito had instituted a surveillance system at the Conchalito scallop banks to keep the poachers out, and the men were approaching the banks by boat. Notes Araceli, “It gets really shallow there so the boats would get stuck in the mud and the men would just end up having shouting matches with the poachers who would always get away with the scallops overland.” Their friend Graciela Olachea designed a new approach. “We could tell where the poachers were accessing the banks by land” continues Araceli, “So me, Graciela, Martha, and several other women started patrolling the land around the banks and scaring off the poachers that way.” The women achieved in 3 months what the men had failed to achieve in 3 years. The poachers were gone. Liliana sighs ruefully, “We should have started with the women.”

But only once the women showed up. NOS, with the support of key funders, had made the controversial decision to pay the fishermen during the restoration period while fishing was suspended. Some of their wives were not impressed with the results. Martha Garcia, speaking for herself and her friend Araceli Méndez says, “As soon as our husbands started receiving payment for not fishing during the restoration, our dream of transforming El Manglito into a beautiful, healthy community became just a job for them. They lost the dream.” Araceli didn’t think their husbands were performing particularly well at the job either. El Manglito had instituted a surveillance system at the Conchalito scallop banks to keep the poachers out, and the men were approaching the banks by boat. Notes Araceli, “It gets really shallow there so the boats would get stuck in the mud and the men would just end up having shouting matches with the poachers who would always get away with the scallops overland.” Their friend Graciela Olachea designed a new approach. “We could tell where the poachers were accessing the banks by land” continues Araceli, “So me, Graciela, Martha, and several other women started patrolling the land around the banks and scaring off the poachers that way.” The women achieved in 3 months what the men had failed to achieve in 3 years. The poachers were gone. Liliana sighs ruefully, “We should have started with the women.”

“In 2016 we joined OPRE, the fishing cooperative NOS helped the men create, and in 2018 we named ourselves Las Guardianas del Conchalito,” recalls Martha. “We wanted to do this our own way, for what we believe in. El Manglito had a bad reputation to the outside, but inside we were a strong, vibrant community. We wanted to build on that.” They were so dedicated that even though NOS had funding to pay only 5 women, 14 joined Las Guardianas and shared the pay. They have been sharing triumphs and trials in a similar fashion ever since.

Las Guardianas take turns telling some of their story. “The mangrove area at Conchalito where we ran off the poachers was a disastrous eyesore that served as a drive-through hotel, a drug dealers’ office, and a neighborhood dump” notes Daniela Bareño. “We reclaimed that land for the neighborhood.” Her colleague Claudia Reyes continued. “The first thing we did was push huge stones across the entryway to stop vehicles from entering, then we organized massive trash cleanups in which we got all segments of the neighborhood engaged. We were taking out 3 tons of trash at a time.” Daniela continued, “While we were cleaning the area, a woman came running in who was being pursued by some scary men. Araceli, Marta and I chased those men away. That incident made us realize that women come here because they know that we are women creating a safe space for women.” El Conchalito is now a beautiful public space for the people of La Paz where people come to walk their dogs, go bird watching, and enjoy the mangroves. Rosa Hale, who tracks usage of the area is particularly proud of one statistic, “The number of women using the space has increased by 70% since we started.”

Las Guardianas take turns telling some of their story. “The mangrove area at Conchalito where we ran off the poachers was a disastrous eyesore that served as a drive-through hotel, a drug dealers’ office, and a neighborhood dump” notes Daniela Bareño. “We reclaimed that land for the neighborhood.” Her colleague Claudia Reyes continued. “The first thing we did was push huge stones across the entryway to stop vehicles from entering, then we organized massive trash cleanups in which we got all segments of the neighborhood engaged. We were taking out 3 tons of trash at a time.” Daniela continued, “While we were cleaning the area, a woman came running in who was being pursued by some scary men. Araceli, Marta and I chased those men away. That incident made us realize that women come here because they know that we are women creating a safe space for women.” El Conchalito is now a beautiful public space for the people of La Paz where people come to walk their dogs, go bird watching, and enjoy the mangroves. Rosa Hale, who tracks usage of the area is particularly proud of one statistic, “The number of women using the space has increased by 70% since we started.”

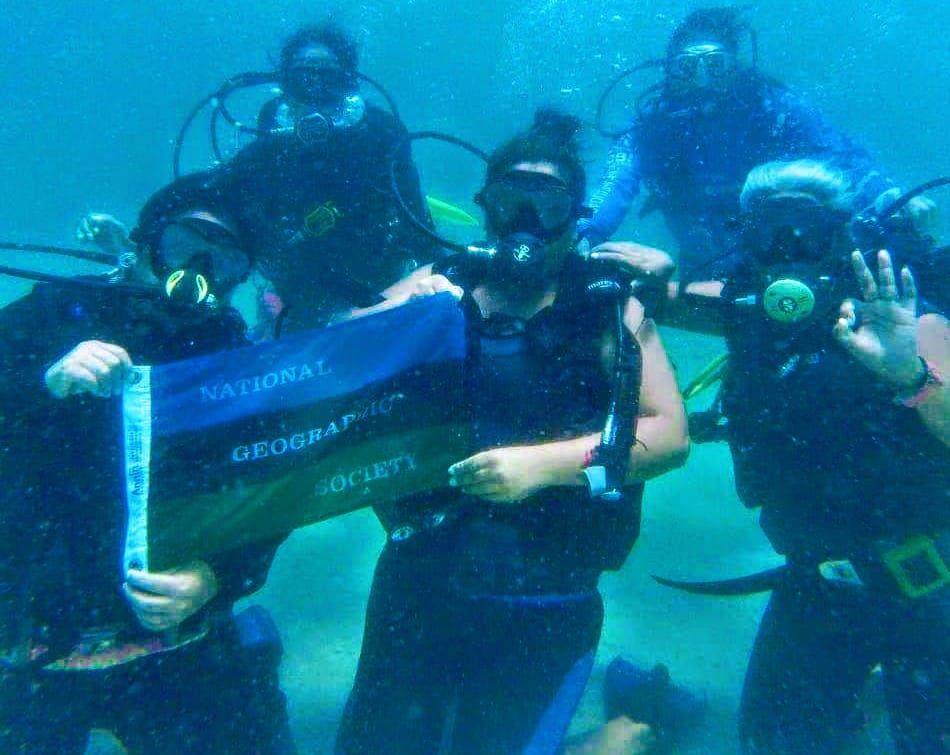

Liliana nominated Las Guardianas for a National Geographic grant. They won and received training in birdwatching to further their dream of guiding people on birding trips through the mangroves. Inspired, Araceli pondered why the women never dove, only the men. They all sent letters to the Women Divers Hall of Fame in the US which awarded a scholarship to each Guardiana who wanted to learn to dive. The photo of Araceli, Martha and Claudia diving with the National Geographic flag is now the stuff of legend.

Liliana nominated Las Guardianas for a National Geographic grant. They won and received training in birdwatching to further their dream of guiding people on birding trips through the mangroves. Inspired, Araceli pondered why the women never dove, only the men. They all sent letters to the Women Divers Hall of Fame in the US which awarded a scholarship to each Guardiana who wanted to learn to dive. The photo of Araceli, Martha and Claudia diving with the National Geographic flag is now the stuff of legend.

And this is how Las Guardianas get things done. They support each other to pursue their own passions, and they inform the NGOs about what support is most beneficial to them. While there’s scarcely a high school diploma amongst them, Araceli is now the “biologist” and is the first woman oyster farmer in La Paz; Daniela is the “engineer” who is working on restoring the Conchalito mangroves in conjunction with WildCoast; Claudia is the “Professor” who teaches people about El Conchalito and takes courses on sustainable business initiatives; Rosa is the “Secretary” who generates use statistics for the estuary; and Martha is the “lawyer” who negotiates deals and recently got Las Guardianas incorporated as their own legal entity. More importantly, she negotiated the permit for the group to restore the Conchalito mangroves, the first time such a permit has ever been issued in La Paz.

And this is how Las Guardianas get things done. They support each other to pursue their own passions, and they inform the NGOs about what support is most beneficial to them. While there’s scarcely a high school diploma amongst them, Araceli is now the “biologist” and is the first woman oyster farmer in La Paz; Daniela is the “engineer” who is working on restoring the Conchalito mangroves in conjunction with WildCoast; Claudia is the “Professor” who teaches people about El Conchalito and takes courses on sustainable business initiatives; Rosa is the “Secretary” who generates use statistics for the estuary; and Martha is the “lawyer” who negotiates deals and recently got Las Guardianas incorporated as their own legal entity. More importantly, she negotiated the permit for the group to restore the Conchalito mangroves, the first time such a permit has ever been issued in La Paz.

“This is the paradigm shift that we are seeing in Baja California Sur now” says McKenzie Campbell, the International Community Fund’s Director of Programs. “Local groups like Las Guardianas have clear hopes, goals and solutions for the future of their communities and ecosystems they steward. They know what they need, and our job as a foundation is to support them in their visions and help provide the tools for their success.”

Liliana is now the director of the Mexican Initiative for Seas and Coasts* and continues her work with Las Guardianas. “Las Guardianas take full advantage of the courses offered by local NGOs, and I gave one on Systemic Thinking. But they really didn’t need it” she recalls. “Las Guardianas are systemic by nature. They embrace the idea that their children, the mangroves, the scallops, the ocean, conservation are all one single issue that can’t be separated.” Liliana, once so skeptical of El Manglito, learned what the women always knew: El Manglito is a strong and dynamic community. It just needs tough, loving guardians to continuously defend, protect and transform it. Las Guardianas.

*TRANSLATOR: Iniciativa por los Mares y las Costas de Mexico