by Bryan Jáuregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures

The National Geographic Society, as venerable an institution as ever graced the shores of the North American continent, has an image problem. Since 1888 the NGS has been supporting adventurers and explorers of every stripe across all the corners of the globe, and such is their success that it is now safe to say that we know it all. Satellites and surveyors, exploring on the ground and from the air, have neatly filled in all the spaces on the old maps where there used to exist nothing but the terrifying admonition: Here be dragons! Does this mean that the Age of Exploration is dead? Is there no more geography left around which a society can coalesce for discovery? Is the NGS, as some naysayers opine, obsolete?

Dr. Jon Rebman in the Sierras

Not a chance. A glance at the interactive NGS global explorers map, which shows thousands of explorers engaged in equally numerous projects across our well-mapped continents, definitively lays that notion to rest. A zoom from the global view of the map down to our own Baja California Sur shows just how vibrant an era of discovery we inhabit. Here you’ll find a hiker symbol in the Sierra La Laguna mountains just outside of Todos Santos, which is the avatar for NGS explorer Dr. Jon P. Rebman, director of the San Diego Natural History Museum’s Botany Department, and author of the definitive Baja California Plant Field Guide. Dr. Rebman’s work demonstrates not only that the Age of Exploration is alive and well, but that we are always gaining a deeper knowledge of the areas depicted on our maps. Perhaps more importantly, we are conserving the existing knowledge of these areas that is in danger of slipping away.

Explains Dr. Rebman. “After 20 years of floristic research on the Baja California peninsula and adjacent islands, my colleagues and I created an annotated, voucher-based checklist of the vascular plants of Baja California. We published this in 2016, and when we compared it to the only floristic manual for the entire Baja California region published by Wiggins in 1980, we found that we had added more than 1,480 plant taxa to the area, including approximately 4,400 plants (3,900 vouchered taxa plus 540 reports), of which 26% are endemic to the region. As part of this process we identified several plants in Baja California that are very rare and only known from one to very few collections.”

“We got focused on the need for conservation efforts to protect the region’s rare flora during a November 2013 expedition in the Cabo Pulmo area to document biodiversity in an area slated for development. My colleagues and I documented two plant species that had been lost, meaning not collected or scientifically documented, for decades. One of these rediscoveries was Stenotis peninsularis (Rubiaceae), a micro-endemic species that was last collected in 1902 by T.S. Brandegee. Yes, that means we had not seen this species in over 110 years!”

Inspired, Rebman continued his quest for the lost plants of Baja during a workplace re-assignment from San Diego to La Paz August 2015 to June 2016. Working with local Baja botanists, he rediscovered approximately 50 plant species in the Cape region that were known from just one, or a tiny number, of historical specimens. But there were more. Specifically, there were 15 more “lost” plants, all endemic to the Baja California peninsula, that had been collected between 1841 and 1985, but had not been seen since. Rebman was intent on finding them. “With the ever-increasing detrimental impacts to native plants and natural landscapes, I realized that the time was now to attempt to re-discover some of Baja California’s very rare, unique, and presently “lost” plants before they are gone forever.” The National Geographic Society agreed to fund the project, and Rebman got his Mexican colleagues – Dr. Jose Luis Leon de la Luz, Dr. Alfonso Medel Narvaez, Dr. Reymundo Dominguez Cadena and Dr. Jose Delgadillo – to join the effort. But how do you find a “lost” plant? It’s not for the faint of heart – spiritually, physically, or intellectually-speaking.

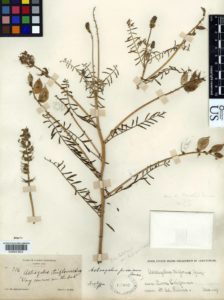

Astragalus piscinus: an image of the holotype specimen deposited in the united States national Herbarium (uS) at the Smithsonian.

Consider. In March 1889, self-taught British botanist Edward Palmer disembarked from a boat at a place on the Baja peninsula that he called “Lagoon Head”, found what he thought was a common weedy plant, and deposited it in an herbarium without further ado. Sometime later, renowned American botanist Marcus E. Jones found it in the herbarium, realized it was a very rare, endemic Baja California plant species, named it Astragalus piscinus, (common name Lagoon Milkvetch), and that was the last time anyone recorded it. In 1884 noted California naturalist Charles Orcutt was in a place he christened “Topo Canyon” when he chanced upon the very rare Physaria palmeri, took a sample, and recorded it with the fledgling San Diego Natural History Museum. No one has noted a sighting of it since. The entire list of the 15 lost plants Rebman and his colleagues set out to find reads like this, with very precise information about the plant, but incredibly imprecise information about the location. Therefore, the first thing the team had to do was pore over the papers, books and letters of the botanists who originally discovered the plants, and do their best to figure out where, exactly, in this 1,000 mile long peninsula, these botanists were when they took their samples. As a result, one of the cool byproducts of the expedition is a map put together by the NGS team that shows the place names used by these early botanists with the actual place names in use today. As every good cartographer knows, maps are an ever-evolving business.

The team narrowed down the possible locations for each plant (“Lagoon Head” turns out to be near Scammons Lagoon and “Topo Canyon” in the mountains of northern Baja), but then they had to actually find these very rare plants in an area that they had already demonstrated held over 4,400 different plants. It would seem almost impossible to make any progress while stopping to investigate all the different possibilities. Unless, of course, you are already so familiar with all the plants that you can immediately discern the one you don’t know, the one you’ve only seen as a specimen or a drawing. John Rebman and his Mexican botanical collaborators are quite possibly the only people alive today to stand a chance of finding any single one of these 15 lost plants. Yet so far, they have looked for ten and found seven. For the others, they need to wait for rain, in Baja, to find the blooms.

“It has not been easy” remarks Rebman. “We were in a desolate area in northern Baja where bandits are known to congregate, and I was looking for Orcutt’s

Astragalus piscinus flowers. Photo by Jon Rebman

Physaria palmeri. There were signs that the bandits were around, and alarm bells were going off in my head. But I had read Orcutt’s journals, had a firm sense of where he had been the day before he discovered the plant as well as the day after, and I really believed I was close. Yet I kept not finding the plant and kept getting more nervous. Finally, I decided that if I hadn’t found it by the time I reached the next tree, I would turn around. I got to the tree, got off my horse, looked down, and there it was. Orcutt, probably found it when he stopped to take a break in a shady spot all those years ago.”

Finding each of the 7 plants they’ve recovered so far has required serious expeditionary skills and effort, with horses, burros, camping gear, local guides, packed water and food. It’s been hot, it’s been dusty and, as we have seen, sometimes it’s been scary. But, as happens with most NGS projects, the results have been quite tidy. Says Rebman, “For each “lost” species that we encountered, we scientifically documented each population using standard protocols to make an herbarium specimen, we recorded all necessary label data, took a census of the populations, and assessed any visible threats to the well-being of the plant populations. Primary herbarium specimens have been deposited in the SD Herbarium at the San Diego Natural History Museum, and duplicate specimens have been deposited in the HCIB Herbarium in La Paz, Baja California Sur, and the BCMEX Herbarium in Ensenada, Baja California. I photographed each re-discovered plant using a digital camera, and these images, along with the map depicting old and new place names together, can be found at bajaflora.org.”

Dr. Alfonso Medel Narváez with Bouchea flabelliformis (Verbenaceae). Photo by Jon Rebman

While looking for the “lost” plants of Baja, Rebman and his team actually made several new discoveries. “From the expeditions we have taken so far, we have already encountered 30 new species previously unknown to science, all sitting in my cabinet awaiting further investigation.”

The NGS likes to quote American explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson, who said you never should have an adventure if your planning is good and you pull off every detail; an adventure is when things go wrong. With multiple expeditions looking for 15 ultra-rare – or possibly even extinct – plant species in poorly-described locations, there is bound to be an abundance of adventure in the process for Rebman and his botanical collaborators. But that is the essence of discovery, the essence of exploration, and Rebman and his team are showing us that there is still a huge amount to be discovered, and re-discovered about the places where the dragons used to roam.