Traveling off the tourist trail in Mexico isn’t simply about dodging the crowds. It’s about the thrill of a colectivo ride through forested landscapes and the awe of stumbling upon a secluded beach where yours are the only footprints.

Many travelers know the cabana-laden beaches of Cancun and the galleries and rooftop scene of San Miguel de Allende. But if you’re ready to trade your resort wristband for a pair of hiking boots or a plate of something you’ve never heard of, lesser-known small towns and quiet islands are calling.

Photo by Newtonian/Shutterstock

1. Find magic beyond the usual suspects

Mexico’s 177 Pueblos Mágicos (Magical Towns) are villages that the government deems particularly charming. While many (like Todos Santos) call their fair share of influencers, not all of them are tourist-packed Instagram traps. Take Calvillo, Aguascalientes, in central Mexico: This guava-scented haven, one of the world’s biggest producers of tropical fruit, is a far cry from the likes of Sayulita. Here, the streets are quieter, the guava candy is abundant, and the town is at the doorstep to the Sierra Fría, known for hiking trails and waterfalls.

If you’re a fan of history and architecture, head to Ahuacatlán or Amatlán de Cañas in western Mexico, both of which offer a peek into the country’s colonial past. The Jesús Nazareno church in Amatlán de Cañas dates back to the 18th century.

2. Embrace the mercado scene

Mexico’s markets are sensory overload in the best way—rows of stalls selling freshly made tortillas, sizzling tacos al pastor, and unrecognizable fruits you’ll want to check out. In lesser-visited towns, markets are a cultural exchange, where you can chat with vendors and maybe learn the secret to their abuela’s mole recipe.

“Mexico City‘s food markets are truly the heartbeat of the city’s culinary and cultural experience,” sayes Karla Tovar, a team member at Bikes and Munchies, a cycling and food tour company based in Mexico City. “Exploring them is one of the best ways to dive into the local food scene and understand the traditions that shape Mexican cuisine.”

While in Mexico City, she recommends hitting up markets like Mercado San Juan for gourmet and exotic food lovers, Mercado de Coyoacan for traditional Mexican snacks, or the Mercado de Jamaica for fresh flowers and traditional food like tlacoyos, which are stuffed corn masa cakes.

Oaxaca‘s Mercado 20 de November is another such dizzying display. Overflowing burlap sacks of multi-colored spices sit next to barrels of dried chilies, while the smell of achiote wafts through the air. Wander the aisles to uncover everything from crispy tlayudas (charcoal-grilled tortillas topped with meat, beans, and vegetables) to roasted grasshoppers.

Over in the central city of Puebla, visit the Mercado de Sabores and pick up a plump, overstuffed cemita, a thick sandwich filled with meat, avocado, cheese, and chipotle.

Photo by astudio/Shutterstock

3. Public transport is your best friend

Think Mexico is all about flights and rental cars? Think again. Try hopping on a bus or a colectivo (a small, shared van), where you’ll ride with locals and, sometimes, a badly dubbed action movie playing on repeat, depending on the length of the trip. Plus, you may meet other travelers and dust off your Spanish with locals.

Buses and colectivos, with their many stops connecting remote parts of the country, make it easier to get to more hard-to-reach destinations. In Yucatan, for example, colectivos can take you from bustling Merida to the white-sand beaches of Celestun and other towns along the Gulf Coast.

Photo by Just Another Photographer/Shutterstock

4. Celebrate like a local

While Cancun has its foam parties, smaller towns throw celebrations that are both intimate and electrifying. Whether it’s the Festival de Calaveras (end of October/early November) in Aguascalientes or the Guelaguetza Indigenous culture celebration festival in Oaxaca (July), you’ll find music, dancing, and food that outshines any resort buffet.

The Fiesta de la Candelaria in Tlacotalpan, a town by the Gulf of Mexico, blends Spanish and Afro-Cuban influences. Son jarocho music, a local guitar folk music fusing Spanish, Indigenous, and African culture, fills the air in early February as residents dress in vibrant red costumes.

And definitely don’t skip the quirkier festivals. How about the Noche de Rábanos (Night of the Radishes), when people create works of art out of the vegetable, in Oaxaca? Or a gathering of healers and shamans in Catemaco, Veracruz, for La Noche de Brujas (Night of the Witches)?

5. Dive into nature

“While much better known for its rich history and culture, Mexico is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world and offers world-class wildlife, nature, and adventure opportunities for even the most well traveled,” says Zach Rabinor, CEO of travel agency Journey Mexico.

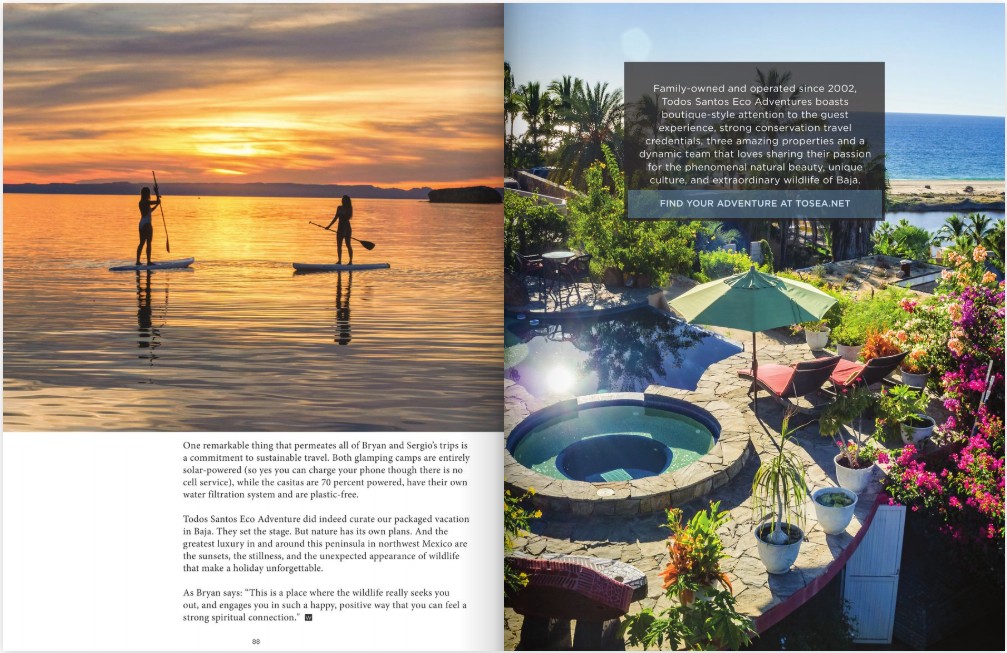

Start with Espíritu Santo, a UNESCO-protected island off the coast of La Paz. Here, turquoise waters meet pink sandstone cliffs, and the sea lions are always ready for a swim. Authorized tours like On Board Baja will take you sailing around the island, hiking along its rugged trails, and picnicking on its remote beaches.

For an off-grid experience, Islas Marías is your next stop. Once a penal colony, this cluster of islands opened for tourism in 2024 offers a glimpse into dozens of endemic species. Because the islands are located 60 miles off the Pacific Coast of Nayarit, the only way to get there is by ferry. You can depart from either Mazatlan or San Blas and, currently, all visitors must be part of a three-day, two-night package that includes a tour guide and accommodations.

And let’s not forget the parks and preserves: Las Pozas in Xilitla is full of waterfalls and jungle paths, while El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve in Baja California Sur offers whale-watching and desert landscapes that are awe inspiring. (Baja Ecotours specializes in whale-watching tours in the biosphere.)

6. Reconsider the resort

Ditch the cookie-cutter resorts and check into boutique hotels and haciendas in small towns. They’re not only more intimate but also steeped in the area’s culture. Take the Hacienda el Carmen Hotel & Spa, which occupies a 17th-century structure less than 50 miles from Guadalajara. Inside the ochre-and-brick facade, guests can dine alfresco to the sounds of classical guitar, while a small spa and stables set the scene for on-site activities.

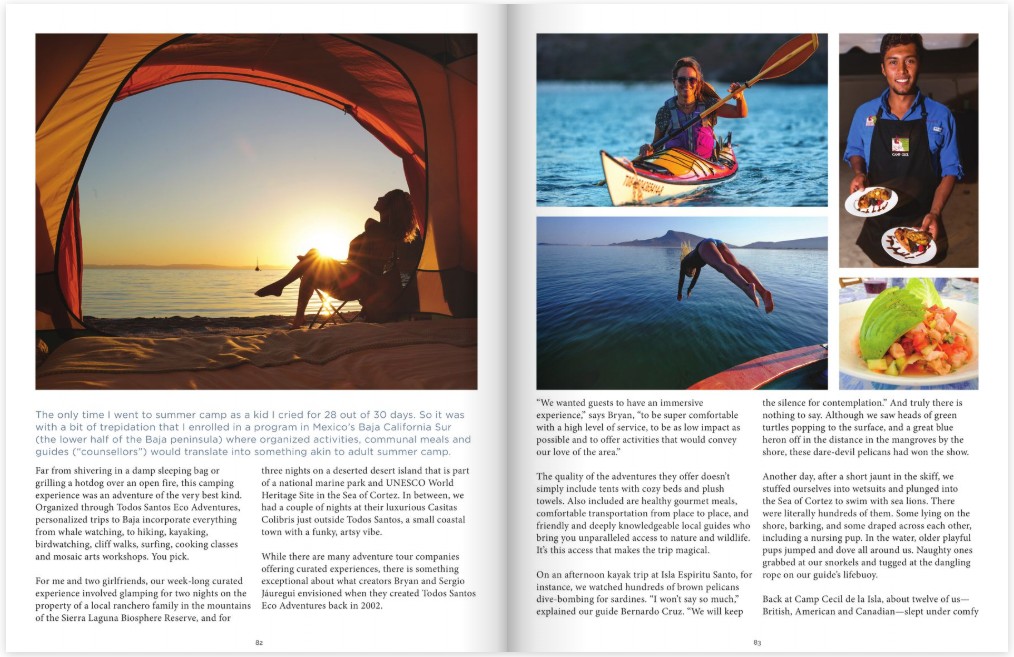

If you’re loving your time on Island Espiritu Santo, consider a glamping adventure with Todos Santos Eco Adventures’ Camp Cecil. Overlooking one of the uninhabited island’s most attractive beaches, the camp features cozy tents, an on-site chef, and drinks under the stars.

Photo by Cenz07/Shutterstock

7. Avoid major cruise ports

If you’re cruising around Mexico, steer clear of itineraries that stick to well-trodden ports like Cozumel or Cabo San Lucas. Instead, seek cruises that stop at lesser-known places such as Loreto, where you can kayak in the Sea of Cortez, or Progreso, a gateway to the Yucatan’s cenotes and ancient ruins.

By avoiding major ports, you’ll bypass crowds of disembarking passengers and enjoy a more relaxed, authentic vibe. Smaller coastal towns and islands like La Paz or Huatulco offer scenic beaches and seafood to rival the big-name spots like Puerto Vallarta or Cabo San Lucas—without the chaos.

NOS adapted its thinking. They started reaching out to the fishermen through their children by supporting local soccer teams and eventually the fishermen agreed to meet with them. “When we first went into El Manglito we thought we knew everything about fisheries conservation and all we had to do was convince the fishermen” recalls Liliana. “But we soon realized our approach was not working so we started talking in a very different way. And by that I mean we, NOS, stopped talking. We started listening. And it was beautiful how the whole idea of restoration emerged from them.”

NOS adapted its thinking. They started reaching out to the fishermen through their children by supporting local soccer teams and eventually the fishermen agreed to meet with them. “When we first went into El Manglito we thought we knew everything about fisheries conservation and all we had to do was convince the fishermen” recalls Liliana. “But we soon realized our approach was not working so we started talking in a very different way. And by that I mean we, NOS, stopped talking. We started listening. And it was beautiful how the whole idea of restoration emerged from them.” But they were resilient. “The fishermen knew it was possible to bring the callo de hacha back, to restore their original fishing area” says Liliana. “We didn’t know it, but they did.” The fishermen knew where the richest points in the bay were for the scallops and knew what needed to be done. “We had assumed that they were evil fishermen and that we were going to save them. Turns out, they knew exactly how to save themselves.” Thus started the callo de hacha restoration project that took seven years and attracted people from all around the world – biologists, conservationists, impact investors. “Everything was happening as Alejandro and that team had dreamed. It was beautiful.”

But they were resilient. “The fishermen knew it was possible to bring the callo de hacha back, to restore their original fishing area” says Liliana. “We didn’t know it, but they did.” The fishermen knew where the richest points in the bay were for the scallops and knew what needed to be done. “We had assumed that they were evil fishermen and that we were going to save them. Turns out, they knew exactly how to save themselves.” Thus started the callo de hacha restoration project that took seven years and attracted people from all around the world – biologists, conservationists, impact investors. “Everything was happening as Alejandro and that team had dreamed. It was beautiful.” But only once the women showed up. NOS, with the support of key funders, had made the controversial decision to pay the fishermen during the restoration period while fishing was suspended. Some of their wives were not impressed with the results. Martha Garcia, speaking for herself and her friend Araceli Méndez says, “As soon as our husbands started receiving payment for not fishing during the restoration, our dream of transforming El Manglito into a beautiful, healthy community became just a job for them. They lost the dream.” Araceli didn’t think their husbands were performing particularly well at the job either. El Manglito had instituted a surveillance system at the Conchalito scallop banks to keep the poachers out, and the men were approaching the banks by boat. Notes Araceli, “It gets really shallow there so the boats would get stuck in the mud and the men would just end up having shouting matches with the poachers who would always get away with the scallops overland.” Their friend Graciela Olachea designed a new approach. “We could tell where the poachers were accessing the banks by land” continues Araceli, “So me, Graciela, Martha, and several other women started patrolling the land around the banks and scaring off the poachers that way.” The women achieved in 3 months what the men had failed to achieve in 3 years. The poachers were gone. Liliana sighs ruefully, “We should have started with the women.”

But only once the women showed up. NOS, with the support of key funders, had made the controversial decision to pay the fishermen during the restoration period while fishing was suspended. Some of their wives were not impressed with the results. Martha Garcia, speaking for herself and her friend Araceli Méndez says, “As soon as our husbands started receiving payment for not fishing during the restoration, our dream of transforming El Manglito into a beautiful, healthy community became just a job for them. They lost the dream.” Araceli didn’t think their husbands were performing particularly well at the job either. El Manglito had instituted a surveillance system at the Conchalito scallop banks to keep the poachers out, and the men were approaching the banks by boat. Notes Araceli, “It gets really shallow there so the boats would get stuck in the mud and the men would just end up having shouting matches with the poachers who would always get away with the scallops overland.” Their friend Graciela Olachea designed a new approach. “We could tell where the poachers were accessing the banks by land” continues Araceli, “So me, Graciela, Martha, and several other women started patrolling the land around the banks and scaring off the poachers that way.” The women achieved in 3 months what the men had failed to achieve in 3 years. The poachers were gone. Liliana sighs ruefully, “We should have started with the women.” Las Guardianas take turns telling some of their story. “The mangrove area at Conchalito where we ran off the poachers was a disastrous eyesore that served as a drive-through hotel, a drug dealers’ office, and a neighborhood dump” notes Daniela Bareño. “We reclaimed that land for the neighborhood.” Her colleague Claudia Reyes continued. “The first thing we did was push huge stones across the entryway to stop vehicles from entering, then we organized massive trash cleanups in which we got all segments of the neighborhood engaged. We were taking out 3 tons of trash at a time.” Daniela continued, “While we were cleaning the area, a woman came running in who was being pursued by some scary men. Araceli, Marta and I chased those men away. That incident made us realize that women come here because they know that we are women creating a safe space for women.” El Conchalito is now a beautiful public space for the people of La Paz where people come to walk their dogs, go bird watching, and enjoy the mangroves. Rosa Hale, who tracks usage of the area is particularly proud of one statistic, “The number of women using the space has increased by 70% since we started.”

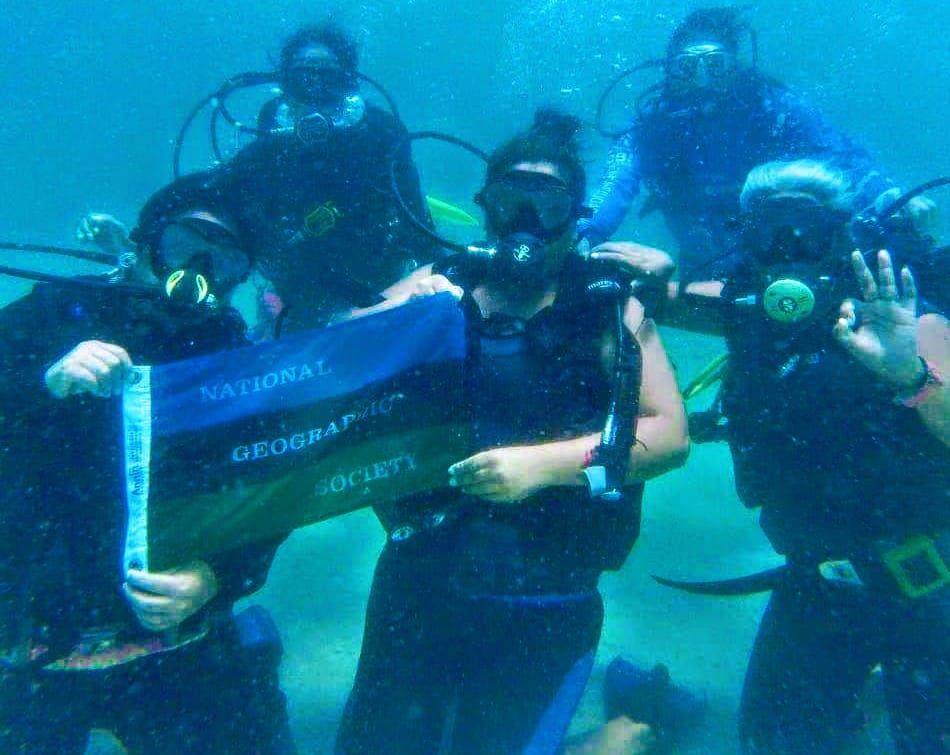

Las Guardianas take turns telling some of their story. “The mangrove area at Conchalito where we ran off the poachers was a disastrous eyesore that served as a drive-through hotel, a drug dealers’ office, and a neighborhood dump” notes Daniela Bareño. “We reclaimed that land for the neighborhood.” Her colleague Claudia Reyes continued. “The first thing we did was push huge stones across the entryway to stop vehicles from entering, then we organized massive trash cleanups in which we got all segments of the neighborhood engaged. We were taking out 3 tons of trash at a time.” Daniela continued, “While we were cleaning the area, a woman came running in who was being pursued by some scary men. Araceli, Marta and I chased those men away. That incident made us realize that women come here because they know that we are women creating a safe space for women.” El Conchalito is now a beautiful public space for the people of La Paz where people come to walk their dogs, go bird watching, and enjoy the mangroves. Rosa Hale, who tracks usage of the area is particularly proud of one statistic, “The number of women using the space has increased by 70% since we started.” Liliana nominated Las Guardianas for a National Geographic grant. They won and received training in birdwatching to further their dream of guiding people on birding trips through the mangroves. Inspired, Araceli pondered why the women never dove, only the men. They all sent letters to the Women Divers Hall of Fame in the US which awarded a scholarship to each Guardiana who wanted to learn to dive. The photo of Araceli, Martha and Claudia diving with the National Geographic flag is now the stuff of legend.

Liliana nominated Las Guardianas for a National Geographic grant. They won and received training in birdwatching to further their dream of guiding people on birding trips through the mangroves. Inspired, Araceli pondered why the women never dove, only the men. They all sent letters to the Women Divers Hall of Fame in the US which awarded a scholarship to each Guardiana who wanted to learn to dive. The photo of Araceli, Martha and Claudia diving with the National Geographic flag is now the stuff of legend. And this is how Las Guardianas get things done. They support each other to pursue their own passions, and they inform the NGOs about what support is most beneficial to them. While there’s scarcely a high school diploma amongst them, Araceli is now the “biologist” and is the first woman oyster farmer in La Paz; Daniela is the “engineer” who is working on restoring the Conchalito mangroves in conjunction with WildCoast; Claudia is the “Professor” who teaches people about El Conchalito and takes courses on sustainable business initiatives; Rosa is the “Secretary” who generates use statistics for the estuary; and Martha is the “lawyer” who negotiates deals and recently got Las Guardianas incorporated as their own legal entity. More importantly, she negotiated the permit for the group to restore the Conchalito mangroves, the first time such a permit has ever been issued in La Paz.

And this is how Las Guardianas get things done. They support each other to pursue their own passions, and they inform the NGOs about what support is most beneficial to them. While there’s scarcely a high school diploma amongst them, Araceli is now the “biologist” and is the first woman oyster farmer in La Paz; Daniela is the “engineer” who is working on restoring the Conchalito mangroves in conjunction with WildCoast; Claudia is the “Professor” who teaches people about El Conchalito and takes courses on sustainable business initiatives; Rosa is the “Secretary” who generates use statistics for the estuary; and Martha is the “lawyer” who negotiates deals and recently got Las Guardianas incorporated as their own legal entity. More importantly, she negotiated the permit for the group to restore the Conchalito mangroves, the first time such a permit has ever been issued in La Paz.