by Sonya Bradley | Blog

Photo by Ernesto Lopez

Don Cata and the Wild Bulls of Baja

by Bryan Jáuregui

Lidia bulls are running wild in the mountains of Baja California Sur – at least those who can outrun Don Catarino Rosas Espinosa. Lidia bulls, also known as Spanish Fighting Bulls, are a distinctive breed of cattle from the Iberian Peninsula that are known for their aggressiveness, strength and stamina. They have nothing on Don Cata.

The Lidia bulls burst onto the Sierra La Laguna fauna scene in 1986 when a Miraflores rancher named Collins grew older and moved away, freeing his milk cows and bulls of different breeds to roam, including the Lidia bulls. In 1989 Don Cata, then 36 years old, struck a deal with the Collins descendants to round up as many of the bulls as possible in exchange for 35% of the proceeds when they were sold. His bull hunting career was launched.

“I hunted the bulls from my 30s through my 50s” recalls Don Cata, who still hunts feral pigs today at the age of 72. “Most of the bulls we encountered over the years were totally wild and had never seen humans before.” Don Cata had a remarkable methodology for hunting the bulls. “I always had two dogs, a Pitbull and a German Shepherd. I would look for the footprint of the bull, then send the dogs to run after it. I would run right behind them on foot as there was no way that horses or mules could navigate that terrain. Usually after the first 6 or 7 kilometers the dogs and I would catch up with the bull then he would run again. Usually after the third run – which sometimes meant a total 15 kilometers of terrain covered – the bull would finally tire and lean against a tree.”

Don Cata not only ran after the bull and the dogs, but did so while wearing two lengths of rope across his chest (“I looked like Pancho Villa”) and one around his waist. Once the bull finally tired and was resting against a tree, Don Cata would lasso its horns and tie its head to the tree with one rope, then use another rope to lasso a hind leg and tie it to another tree such that the rope would tighten when the bull struggled. He would then use the third rope to lasso the bull’s front legs. That third lasso would bring the bull down and Don Cata would then tie up the final hind leg. So far so good.

But Don Cata, who is all of 72 kilograms / 158 pounds, now has a seriously angry, 600 kilo / 1,300 pound animal – whose breed is notorious for its aggressiveness – tied up in rugged mountain terrain while traveling on foot. He only gets paid when he delivers the bull alive several thousand feet below. Sheer physicality, stamina and mad cowboy skills have gotten him this far. Now it’s time to out psych the bull. “The bulls were so angry that they usually needed about 90 minutes to calm down” recalls Don Cata, “so the dogs and I would wait downwind while they quieted. Then I would go back, release one of the legs and tie a stick to the foreleg such that it stopped the bull from running. I would then leave again and let the bull get used to the stick. Then the next time the bull saw me he would be very tired and very afraid of me, so I could release all the ropes. If he lunged for me I could parry him away with a stick that I used like a lance. In this way I could get a bull down the mountain in 2-3 days.”

Don Cata created a type of corral where he would collect 18 to 20 bulls, put bells on them, then get them to the road where a truck would pick them up, weigh them and deliver them to the Collins family. “I got over 600 bulls like this” recalls Dona Cata. In a masterful piece of understatement about his running skills Don Cata notes, “I was fast.”

Don Cata created a type of corral where he would collect 18 to 20 bulls, put bells on them, then get them to the road where a truck would pick them up, weigh them and deliver them to the Collins family. “I got over 600 bulls like this” recalls Dona Cata. In a masterful piece of understatement about his running skills Don Cata notes, “I was fast.”

The bulls scored some points as well. “Once I was tying a bull’s head to a tree and trying to do it quickly because the bull had already closed its eyes in anticipation of hitting me. I was moving fast and slipped. My rope was round the bull’s head so when I went down the whole 600 kilo body of the bull came down on top of me. It really messed up my knee.” A local rancher patched him up and suggested he put his bull hunting days behind him. “I didn’t listen. 3 days later I was running after the bulls again.” (His knee remains a little wonky looking to this day.) And one bull did succeed in head-butting him. Luckily the horn just grazed his skull but the force caused the fur of the bull’s head to burn his ear.

As he moved into his 50s Don Cata took on another feral animal – pigs. “When I was a child ranchers used to raise a lot of pigs, not to sell, just to eat. When the hurricanes hit the pigs would head to the hills to eat all the acorns, pine nuts etc that had been blown off the trees, then head back home.”

Then in 1997 a major hurricane hit off the coast of Los Cabos and it rained for 3 days straight. This created an enormous bounty of food and water for the pigs so in the ensuing years their population exploded. “There were so many pigs that they were eating all the grass in the valley of the mountain and really damaging the ecosystem” recalls Don Cata. The Sierra La Laguna Biosphere Reserve park authorities decided that some of the pigs needed to be eradicated so they contracted Don Cata for the job. “Thankfully the pigs prefer terrain that is accessible by horse and mule” the older Don Cata laughingly notes.

Then in 1997 a major hurricane hit off the coast of Los Cabos and it rained for 3 days straight. This created an enormous bounty of food and water for the pigs so in the ensuing years their population exploded. “There were so many pigs that they were eating all the grass in the valley of the mountain and really damaging the ecosystem” recalls Don Cata. The Sierra La Laguna Biosphere Reserve park authorities decided that some of the pigs needed to be eradicated so they contracted Don Cata for the job. “Thankfully the pigs prefer terrain that is accessible by horse and mule” the older Don Cata laughingly notes.

While pig hunting requires less stamina than bull hunting, it is infinitely more dangerous. The pigs have long, sharp tusks and are extremely strong. To catch them, Don Cata sends his dog to track a pig and grab it by the ear. Don Cata then gets off his horse, picks the pig up by its hind leg, and shoots it. While many ranchers use knives for the kill, Don Cata hunts with CIBNOR, the Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste S.C., and they want to weigh and measure the pigs without the blood loss that accompanies a knife wound. CIBNOR takes samples of each pig’s organs to make sure the pig is healthy enough to be eaten. Says Don Cata, “I usually hunt for 4 days and come down with 80 to 100 kilos of meat to sell.” Don Cata reckons he’s caught over 1,000 pigs.

Pig hunting is intimate business and Don Cata has far more scars from pigs than bulls. It is therefore perhaps not surprising to learn that while Don Cata is famous for his hunting skills, he is legendary for his healing skills, and people come from all across the state to seek his help.

Don Cata is the patriarch of the Rosas family and preserving the ranchero way of life is a key family goal at their beautiful Rancho Ecológico el Refugio in the Sierra mountains. Don Cata himself embodies the ranchero ideal, with both the strength and skill to confront wild forces and the wisdom and talent to restore health and balance in his community. He manifests a profound connection with nature. He is a hunter-healer.

The Family at El Refugio / Photo by Mike Brinkman

by Sonya Bradley | Blog

The Mission is Simple: Empower Guides, foster cross-cultural conservation practices, and celebrate world ecosystems.

Todos Santos Eco Adventures is a proud member of the Kusini Collection, a hand-picked portfolio of sustainable, owner/founder-operated camps, lodges and tour operators in Africa, Asia and the Americas. Some years ago we presented the idea of a guide exchange program with the other members. We’re extremely thrilled to share that it is a complete success and continues to grow and enrich the lives of not only our guides but all of us! A recent exchange just took place with Ultimate Safaris from Namibia and they have shared the following.

“As a leader in conservation-based luxury travel in Namibia, we have once again demonstrated our commitment to people and the planet with our third consecutive international guide exchange, investing over N$ 300,000 into the initiative since its inception.

This year, Jason Nengola, Ultimate Safaris’ 2024 Ultimate Guide of the Year, travelled to Baja California, Mexico, for a three-week immersion experience with Todos Santos Eco Adventures. The exchange underscores a shared mission between the two companies: to empower guides, foster cross-cultural conservation practices, and celebrate the ecosystems they passionately protect.

This year, Jason Nengola, Ultimate Safaris’ 2024 Ultimate Guide of the Year, travelled to Baja California, Mexico, for a three-week immersion experience with Todos Santos Eco Adventures. The exchange underscores a shared mission between the two companies: to empower guides, foster cross-cultural conservation practices, and celebrate the ecosystems they passionately protect.

“The guide swap initiative is a great opportunity for interaction and learning between people on different sides of the world who may have differing geographies, wildlife, and weather—but who share the same dedication to conservation and community,” said Tristan Cowley, Co-founder and Managing Director of Ultimate Safaris.

Jason’s journey from Namibia’s vast deserts to Mexico’s vibrant marine ecosystems was nothing short of transformative. From snorkeling and scuba diving to whale watching and leather-making from cactus, Jason embraced new perspectives—both professionally and personally.

“Imagine Damaraland with an ocean,” Jason remarked. “Being a guest, not a guide, helped me understand how our guests must feel. It was a humbling and eye-opening experience.”

He encountered four species of whales—Blue, Humpback, Fin, and Grey—an awe-inspiring highlight that shifted his perspective on control, nature, and the role of a guide. In addition to nature-based activities, the exchange allowed Jason to explore Mexico’s strong connection to its local culture and cuisine—an experience that left a lasting impression.

“In Namibia, we have so many rich cultures and traditions to share,” he said. “The food in Mexico inspired me to think about how we can better incorporate Namibian cuisine into our guest experiences.”

Jason also reconnected with Axel Herrera, a Todos Santos guide who had previously visited Namibia through the same exchange program—reinforcing the mutual value and long-term relationships fostered by this initiative.

Later this year, a Mexican guide will travel to Namibia for the next chapter of this growing partnership, continuing the spirit of knowledge-sharing, cultural appreciation, and environmental stewardship.

The Ultimate Safaris and Todos Santos Eco Adventures guide exchange initiative represents a model for global collaboration in eco-tourism—building not only better guides, but stronger bridges between continents, cultures, and conservation efforts.”

by Sonya Bradley | Blog

A Holistic Approach to Sustainability in Mexico

Recently REMOTE LA placed a spotlight on the efforts of select partners, who are demonstrating that Latin America and the Caribbean are not just embracing sustainable and regenerative tourism—they are shaping a resilient future. Through carbon offset and capture programs, conservation initiatives, responsible business practices and bold climate action plans, these companies are proving that tourism can—and must—be a force for good. Their work reassures us that conscious international travelers can continue to visit Latin America while actively contributing to the well-being of its destinations.

We proudly share what they had to say about us:

Todos Santos Eco Adventures (TOSEA) is at the forefront of responsible tourism in Baja California Sur, Mexico, integrating sustainability into every aspect of its operations. As a member of the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) and a signatory of the Future of Tourism Coalition, TOSEA spearheads initiatives that drive conservation and sustainability in the region. One of its most ambitious projects is supporting the Alianza Cero Basura, which works to establish Mexico’s first Zero Waste destination in Todos Santos and El Pescadero, setting a groundbreaking precedent for responsible tourism.

TOSEA is also taking decisive action against climate change through its partnership with Tomorrow’s Air, significantly increasing its contributions to carbon capture, having successfully removed and stored three tons of CO₂ so far. Their holistic approach to sustainability extends beyond waste reduction and emissions mitigation. TOSEA is deeply involved in conservation efforts and embedding regenerative principles into its tourism model, demonstrating that sustainability is not just about minimizing harm; it’s about fostering a thriving future for both local communities and the environment.

by Sonya Bradley | Blog

Las Guardianas del Conchalito

It was 2010 and El Manglito had a reputation as one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in La Paz. Outsiders perceived it as a place where trouble thrived. Taxis often refused to enter. “When we decided to set up our office there, I really thought it was a crazy idea” recalls Liliana Gutierrez, the former program director for Noroeste Sustentable (NOS) in Baja California Sur. “NOS director Alejandro Robles stood in the middle of this maligned place and talked about building a sustainability demonstration center so that people could really see what sustainability could look like in La Paz. Sam Walton wanted to have organic gardens and fisheries restoration projects. He wanted to bring in experts from all over the world to meet the fishermen. Really smart people shared this vision with them, and all I could think is that all these people are completely crazy.” As it turns out, she was right. Continues Liliana, “They were crazy. They were crazy in the most needed way that we need crazy people in the world because from that moment began an amazing story.” And everything they envisioned has come to pass. But that was only once the women got involved.

“Our first communication from the fishermen in El Manglito was a rock through the window of our offices” recalls Liliana. Like the rest of their neighborhood, the fishermen of El Manglito had a particularly bad reputation and were infamous for illegally poaching fish in the protected waters around Isla Espiritu Santo. NOS was part of an Espiritu Santo surveillance alliance that had been literally chasing them in boats in an attempt to restrict their nocturnal thievery, so the rock was not a total surprise. “It was a time of high polarization” notes Liliana with a nod to understatement. “Conservation NGOs like NOS had very strong ideas against the fishermen and the fishermen against the NGOs.”

NOS adapted its thinking. They started reaching out to the fishermen through their children by supporting local soccer teams and eventually the fishermen agreed to meet with them. “When we first went into El Manglito we thought we knew everything about fisheries conservation and all we had to do was convince the fishermen” recalls Liliana. “But we soon realized our approach was not working so we started talking in a very different way. And by that I mean we, NOS, stopped talking. We started listening. And it was beautiful how the whole idea of restoration emerged from them.”

NOS adapted its thinking. They started reaching out to the fishermen through their children by supporting local soccer teams and eventually the fishermen agreed to meet with them. “When we first went into El Manglito we thought we knew everything about fisheries conservation and all we had to do was convince the fishermen” recalls Liliana. “But we soon realized our approach was not working so we started talking in a very different way. And by that I mean we, NOS, stopped talking. We started listening. And it was beautiful how the whole idea of restoration emerged from them.”

Many of the fishing families of El Manglito are descended from the Yaqui Indians who left Sonora at the turn of the last century to escape government persecution. The Yaquis are renowned freedivers and used these skills in La Paz to fish for the huge scallops called callo de hacha in the Ensenada de La Paz, a lagoon inside the Bay of La Paz whose shores reach El Manglito. But by 2008 their lagoon was dead and their callo de hachas with it. Raw sewage from the city was being pumped in, and tons of the city’s garbage was being picked up by hurricanes and dumped there. The fishermen therefore started going to the rich waters around Isla Espiritu Santo to fish. But in 2010 the Espiritu Santo Archipelago was declared a marine national park, and the fishermen of El Manglito were transformed overnight from legal actors into illegal poachers. They had not been consulted on the process.

But they were resilient. “The fishermen knew it was possible to bring the callo de hacha back, to restore their original fishing area” says Liliana. “We didn’t know it, but they did.” The fishermen knew where the richest points in the bay were for the scallops and knew what needed to be done. “We had assumed that they were evil fishermen and that we were going to save them. Turns out, they knew exactly how to save themselves.” Thus started the callo de hacha restoration project that took seven years and attracted people from all around the world – biologists, conservationists, impact investors. “Everything was happening as Alejandro and that team had dreamed. It was beautiful.”

But they were resilient. “The fishermen knew it was possible to bring the callo de hacha back, to restore their original fishing area” says Liliana. “We didn’t know it, but they did.” The fishermen knew where the richest points in the bay were for the scallops and knew what needed to be done. “We had assumed that they were evil fishermen and that we were going to save them. Turns out, they knew exactly how to save themselves.” Thus started the callo de hacha restoration project that took seven years and attracted people from all around the world – biologists, conservationists, impact investors. “Everything was happening as Alejandro and that team had dreamed. It was beautiful.”

But only once the women showed up. NOS, with the support of key funders, had made the controversial decision to pay the fishermen during the restoration period while fishing was suspended. Some of their wives were not impressed with the results. Martha Garcia, speaking for herself and her friend Araceli Méndez says, “As soon as our husbands started receiving payment for not fishing during the restoration, our dream of transforming El Manglito into a beautiful, healthy community became just a job for them. They lost the dream.” Araceli didn’t think their husbands were performing particularly well at the job either. El Manglito had instituted a surveillance system at the Conchalito scallop banks to keep the poachers out, and the men were approaching the banks by boat. Notes Araceli, “It gets really shallow there so the boats would get stuck in the mud and the men would just end up having shouting matches with the poachers who would always get away with the scallops overland.” Their friend Graciela Olachea designed a new approach. “We could tell where the poachers were accessing the banks by land” continues Araceli, “So me, Graciela, Martha, and several other women started patrolling the land around the banks and scaring off the poachers that way.” The women achieved in 3 months what the men had failed to achieve in 3 years. The poachers were gone. Liliana sighs ruefully, “We should have started with the women.”

But only once the women showed up. NOS, with the support of key funders, had made the controversial decision to pay the fishermen during the restoration period while fishing was suspended. Some of their wives were not impressed with the results. Martha Garcia, speaking for herself and her friend Araceli Méndez says, “As soon as our husbands started receiving payment for not fishing during the restoration, our dream of transforming El Manglito into a beautiful, healthy community became just a job for them. They lost the dream.” Araceli didn’t think their husbands were performing particularly well at the job either. El Manglito had instituted a surveillance system at the Conchalito scallop banks to keep the poachers out, and the men were approaching the banks by boat. Notes Araceli, “It gets really shallow there so the boats would get stuck in the mud and the men would just end up having shouting matches with the poachers who would always get away with the scallops overland.” Their friend Graciela Olachea designed a new approach. “We could tell where the poachers were accessing the banks by land” continues Araceli, “So me, Graciela, Martha, and several other women started patrolling the land around the banks and scaring off the poachers that way.” The women achieved in 3 months what the men had failed to achieve in 3 years. The poachers were gone. Liliana sighs ruefully, “We should have started with the women.”

“In 2016 we joined OPRE, the fishing cooperative NOS helped the men create, and in 2018 we named ourselves Las Guardianas del Conchalito,” recalls Martha. “We wanted to do this our own way, for what we believe in. El Manglito had a bad reputation to the outside, but inside we were a strong, vibrant community. We wanted to build on that.” They were so dedicated that even though NOS had funding to pay only 5 women, 14 joined Las Guardianas and shared the pay. They have been sharing triumphs and trials in a similar fashion ever since.

Las Guardianas take turns telling some of their story. “The mangrove area at Conchalito where we ran off the poachers was a disastrous eyesore that served as a drive-through hotel, a drug dealers’ office, and a neighborhood dump” notes Daniela Bareño. “We reclaimed that land for the neighborhood.” Her colleague Claudia Reyes continued. “The first thing we did was push huge stones across the entryway to stop vehicles from entering, then we organized massive trash cleanups in which we got all segments of the neighborhood engaged. We were taking out 3 tons of trash at a time.” Daniela continued, “While we were cleaning the area, a woman came running in who was being pursued by some scary men. Araceli, Marta and I chased those men away. That incident made us realize that women come here because they know that we are women creating a safe space for women.” El Conchalito is now a beautiful public space for the people of La Paz where people come to walk their dogs, go bird watching, and enjoy the mangroves. Rosa Hale, who tracks usage of the area is particularly proud of one statistic, “The number of women using the space has increased by 70% since we started.”

Las Guardianas take turns telling some of their story. “The mangrove area at Conchalito where we ran off the poachers was a disastrous eyesore that served as a drive-through hotel, a drug dealers’ office, and a neighborhood dump” notes Daniela Bareño. “We reclaimed that land for the neighborhood.” Her colleague Claudia Reyes continued. “The first thing we did was push huge stones across the entryway to stop vehicles from entering, then we organized massive trash cleanups in which we got all segments of the neighborhood engaged. We were taking out 3 tons of trash at a time.” Daniela continued, “While we were cleaning the area, a woman came running in who was being pursued by some scary men. Araceli, Marta and I chased those men away. That incident made us realize that women come here because they know that we are women creating a safe space for women.” El Conchalito is now a beautiful public space for the people of La Paz where people come to walk their dogs, go bird watching, and enjoy the mangroves. Rosa Hale, who tracks usage of the area is particularly proud of one statistic, “The number of women using the space has increased by 70% since we started.”

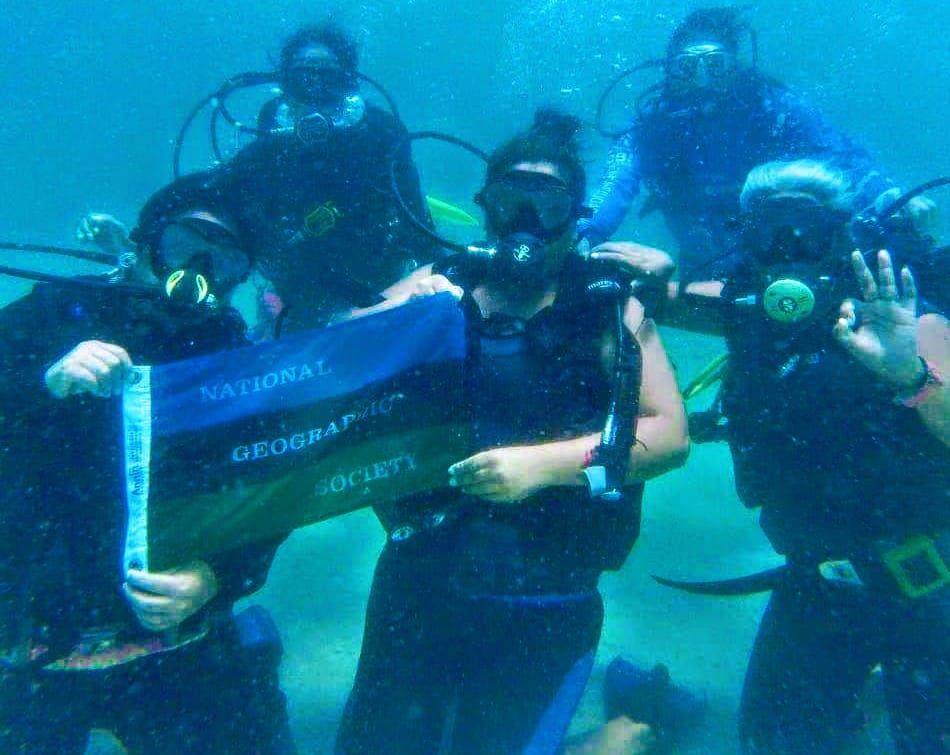

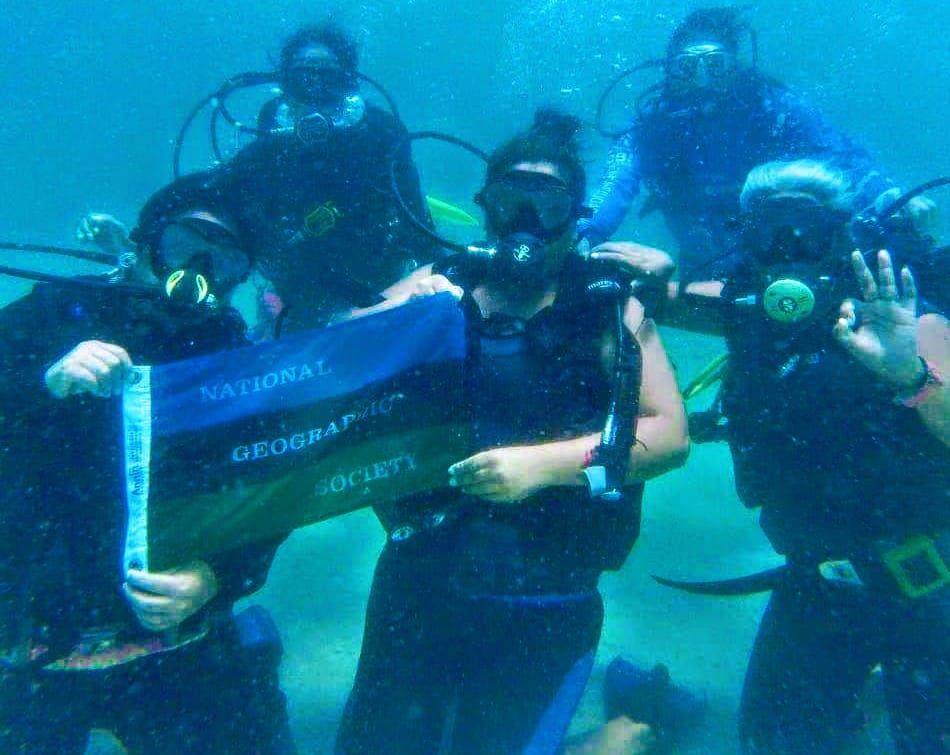

Liliana nominated Las Guardianas for a National Geographic grant. They won and received training in birdwatching to further their dream of guiding people on birding trips through the mangroves. Inspired, Araceli pondered why the women never dove, only the men. They all sent letters to the Women Divers Hall of Fame in the US which awarded a scholarship to each Guardiana who wanted to learn to dive. The photo of Araceli, Martha and Claudia diving with the National Geographic flag is now the stuff of legend.

Liliana nominated Las Guardianas for a National Geographic grant. They won and received training in birdwatching to further their dream of guiding people on birding trips through the mangroves. Inspired, Araceli pondered why the women never dove, only the men. They all sent letters to the Women Divers Hall of Fame in the US which awarded a scholarship to each Guardiana who wanted to learn to dive. The photo of Araceli, Martha and Claudia diving with the National Geographic flag is now the stuff of legend.

And this is how Las Guardianas get things done. They support each other to pursue their own passions, and they inform the NGOs about what support is most beneficial to them. While there’s scarcely a high school diploma amongst them, Araceli is now the “biologist” and is the first woman oyster farmer in La Paz; Daniela is the “engineer” who is working on restoring the Conchalito mangroves in conjunction with WildCoast; Claudia is the “Professor” who teaches people about El Conchalito and takes courses on sustainable business initiatives; Rosa is the “Secretary” who generates use statistics for the estuary; and Martha is the “lawyer” who negotiates deals and recently got Las Guardianas incorporated as their own legal entity. More importantly, she negotiated the permit for the group to restore the Conchalito mangroves, the first time such a permit has ever been issued in La Paz.

And this is how Las Guardianas get things done. They support each other to pursue their own passions, and they inform the NGOs about what support is most beneficial to them. While there’s scarcely a high school diploma amongst them, Araceli is now the “biologist” and is the first woman oyster farmer in La Paz; Daniela is the “engineer” who is working on restoring the Conchalito mangroves in conjunction with WildCoast; Claudia is the “Professor” who teaches people about El Conchalito and takes courses on sustainable business initiatives; Rosa is the “Secretary” who generates use statistics for the estuary; and Martha is the “lawyer” who negotiates deals and recently got Las Guardianas incorporated as their own legal entity. More importantly, she negotiated the permit for the group to restore the Conchalito mangroves, the first time such a permit has ever been issued in La Paz.

“This is the paradigm shift that we are seeing in Baja California Sur now” says McKenzie Campbell, the International Community Fund’s Director of Programs. “Local groups like Las Guardianas have clear hopes, goals and solutions for the future of their communities and ecosystems they steward. They know what they need, and our job as a foundation is to support them in their visions and help provide the tools for their success.”

Liliana is now the director of the Mexican Initiative for Seas and Coasts* and continues her work with Las Guardianas. “Las Guardianas take full advantage of the courses offered by local NGOs, and I gave one on Systemic Thinking. But they really didn’t need it” she recalls. “Las Guardianas are systemic by nature. They embrace the idea that their children, the mangroves, the scallops, the ocean, conservation are all one single issue that can’t be separated.” Liliana, once so skeptical of El Manglito, learned what the women always knew: El Manglito is a strong and dynamic community. It just needs tough, loving guardians to continuously defend, protect and transform it. Las Guardianas.

*TRANSLATOR: Iniciativa por los Mares y las Costas de Mexico

by Sonya Bradley | Blog

Notes for translator:

Bighorn sheep = Borrego Cimarrón

Field Technician = Tecnico

Ecologist = Ecológo

“It was so hot and the terrain was so steep and challenging” recalls La Paz-based bighorn sheep hunting translator Angel Antonio Marquez. “We had to stick to the shadows so the sheep couldn’t see us, making the walking even more difficult. When we were 850 yards from the ram the hunter decided to take the shot. We all thought he was crazy since it was so far and we were not at all surprised when he missed. The bullet went right between that sheep’s legs.” Angel continued, “Now this would have scared away most animals, but there was a female sheep nearby and this male was trying to be macho for her so he just stood there. The hunter got him on the second shot. 850 yards. It is the record for the farthest shot in this area.”

“It was so hot and the terrain was so steep and challenging” recalls La Paz-based bighorn sheep hunting translator Angel Antonio Marquez. “We had to stick to the shadows so the sheep couldn’t see us, making the walking even more difficult. When we were 850 yards from the ram the hunter decided to take the shot. We all thought he was crazy since it was so far and we were not at all surprised when he missed. The bullet went right between that sheep’s legs.” Angel continued, “Now this would have scared away most animals, but there was a female sheep nearby and this male was trying to be macho for her so he just stood there. The hunter got him on the second shot. 850 yards. It is the record for the farthest shot in this area.”

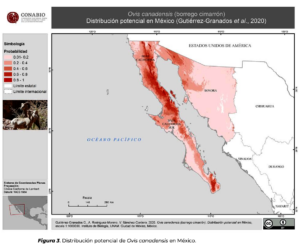

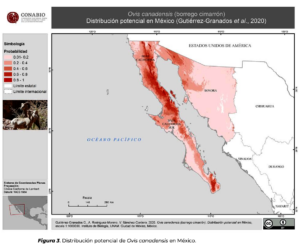

According to CONABIO, Mexico’s National Commission for the Knowledge and Use of Biodiversity, in 1800 over 1 million bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) roamed across the western parts of the US, Canada and northern Mexico. But the introduction of livestock and uncontrolled hunting led to a major decline, and by 1950 there were fewer than 25,000 individual sheep left. The population in northeast Mexico was extirpated and the remaining population in the northwest around Sonora and the Baja peninsula was small and fragmented. It might seem counterintuitive, but hunting is now the main activity, regulated by the Mexican government, helping to stabilize the bighorn sheep population and preserve their habitat.

“This program is an amazing idea” states Biól. Gabriela López Segurajáuregui, the Mexican CITES Scientific Authority Coordinator. “Mexico is a megadiverse country with over 10% of all species in the world. Our conservation challenge is to incentivize people to care for their resources so that they can make a living from them in an ongoing, sustainable way. Bighorn sheep trophy hunting is a major conservation success story in Mexico.”

Gabriela’s colleague M. en C. Luis Guillermo Muñoz Lacy, Chief of the National CITES implementation on Fauna Department, elaborates. “Mexico allows trophy hunting across many species, but bighorn sheep is the most valuable species for hunting in the country, meaning that hunters are willing to pay the most for those permits. The money generated by this program has a tremendously positive economic impact on local communities as well as a tremendously positive conservation impact on the sheep themselves and the lands they roam.” How much money are we talking about? Guillermo explains, “Each bighorn sheep permit in Baja California Sur (BCS) can be sold for USD 50,000 to 90,000. Sonora holds the record at USD 250,000 for one permit. BCS exports about 18 trophies per year.” In other words, it’s a game changer for the rural communities who manage the land and the hunts.

Here’s how it works. In the 1995-1997 timeframe the Mexican government created Conservation Wildlife Management Units (UMAs) to regulate wildlife harvest and non-harvest activities in Mexico, including habitat and species restoration, protection, research and environmental education. In the case of bighorn sheep, UMAs cover most of its habitat. 10 of the UMAs are in BCS and are managed by ejidos, or local communal farmers, and the remainder are across the Sea of Cortez in Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila and Nuevo Leon. Bighorn sheep trophy hunting is carried out within the UMA system in the states of BCS and Sonora. Baja California, the state that occupies the northern half of the Baja peninsula, does not allow hunting.

In 1975 twenty bighorn sheep were reintroduced to Tiburon Island in the Sea of Cortez off the coast of Sonora, and by 2012 that number had grown to 650. Many of those were transplanted to Sonora for repopulation and captive breeding programs and by 2019, the last year for which Sonora published its data, the continental population of bighorn sheep had recovered to 3,829 wild individuals and 4,500 in captivity. By contrast, BCS has only had a couple of reintroduction or reinforcement events and the last aerial survey conducted by SEMARNAT in 2022 estimated about 1,100 individuals in BCS.

The UMAs of BCS pay for a team of technicians to regularly monitor the bighorn sheep population on land, participate in the hunts, and accompany the aerial surveys that are conducted every three years. The technicians are extremely clear in their minds about the value of the trophy program. “If it were not for the economic power of the trophy permits, the Bighorn sheep population would almost certainly have been decimated by now and the ejidos would have sold off most of the land” observes Ing. Antia Duarte Camacho, Field Technician of de Ejido San Jose de la Noria and Ejido Lic. Alfredo V. Bonfil. “The bighorn sheep habitat is all along the Sea of Cortez, making that land extremely valuable.” Her colleague Ecologist Miguel Angel Aguilar Juárez, Field Technician of Ejidos Ley Federal de Aguas 1, 2 and 3 adds, “By 2014 the ejidos, many of which had been impoverished, were really starting to understand the huge, sustained, economic lift flowing from the trophy program. They developed a deep appreciation for the value of the land that they own and the sheep that inhabit it. That is when they all really started working together to make the program work as a whole in BCS. Bighorn sheep move seasonally across a vast territory so corridors are important. Income from bighorn sheep hunting started motivating the ejidos to work together to maintain these huge areas with no other human activities, including the raising of livestock.” CONABIO points to the resulting large-scale habitat conservation and improved connectivity as a major achievement of the trophy hunting program.

The UMAs of BCS pay for a team of technicians to regularly monitor the bighorn sheep population on land, participate in the hunts, and accompany the aerial surveys that are conducted every three years. The technicians are extremely clear in their minds about the value of the trophy program. “If it were not for the economic power of the trophy permits, the Bighorn sheep population would almost certainly have been decimated by now and the ejidos would have sold off most of the land” observes Ing. Antia Duarte Camacho, Field Technician of de Ejido San Jose de la Noria and Ejido Lic. Alfredo V. Bonfil. “The bighorn sheep habitat is all along the Sea of Cortez, making that land extremely valuable.” Her colleague Ecologist Miguel Angel Aguilar Juárez, Field Technician of Ejidos Ley Federal de Aguas 1, 2 and 3 adds, “By 2014 the ejidos, many of which had been impoverished, were really starting to understand the huge, sustained, economic lift flowing from the trophy program. They developed a deep appreciation for the value of the land that they own and the sheep that inhabit it. That is when they all really started working together to make the program work as a whole in BCS. Bighorn sheep move seasonally across a vast territory so corridors are important. Income from bighorn sheep hunting started motivating the ejidos to work together to maintain these huge areas with no other human activities, including the raising of livestock.” CONABIO points to the resulting large-scale habitat conservation and improved connectivity as a major achievement of the trophy hunting program.

Bighorn sheep are extremely desirable among trophy hunters and are part of the sheep Grand Slam. Which leads to the question: how many sheep can you hunt without hurting the species? This is one of the critical questions that Gabriela López of the Mexican CITES Scientific Authority (CONABIO) and her team focus on. The UMAs organize to finance an aerial census of the bighorn sheep habitat every three years in the September-December timeframe. The survey is done in coordination with SEMARNAT, CONABIO and key experts. It is this survey that serves as the basis for issuing the harvest rate. Gabriela explains further, “We estimate that the aerial survey team makes visual contact with roughly 30% of the total population. As a precautionary measure we determine the number of trophy hunts that will be allowed based solely on the number of individual sheep actually observed, not the extrapolated number.” Only males that are 6 years or older can be hunted – an estimation made by the size of the horns – and the number to be hunted cannot exceed 10-20% of the observed population in each region. (The hunting guides note that hunters are not tempted by younger rams as they are going for the largest horns possible and those are, by definition, found on the oldest males. Males can live 9-12 years in the wild.) Based on the aerial survey of 2019, 18 trophy (harvest) permits were issued per year to the UMAS of BCS by SEMARNAT based on the technical and scientific advice of CONABIO. That number increased to 19 trophy permits per year based on the 2022 aerial survey. The next aerial survey will be conducted in December of 2025.

Once SEMARNAT issues the number of CITES permits to export trophies (CITES is the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) the UMAs work with brokers based in the United States to auction off the permits in places like Las Vegas and Reno. The brokers retain 15% of the permit fee and the remainder goes to the UMA and its ejido. The UMAs would like to see the auctions moved to BCS.

The horns and skin of the bighorn sheep shot by the hunter at 850 yards are still in the office of the technical team in La Paz. Issuance of the CITES permit for the trophy to be transported across international borders to the US-based hunter could take 3-4 months (SEMARNAT must also be consulted). CITES is a legally binding agreement between governments that works to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals or plants does not threaten the survival of the species. Only Mexico’s bighorn sheep population is listed on CITES Appendix II which covers species that are not necessarily threatened by international trade but that are deemed worthy of a close eye so that they do not slip into the highest category of endangerment, Appendix I. When weighing the permit to send this hunter his trophy they will carefully review, among other things, the report of the UMA technician who accompanied the hunt and took detailed notes on the geographical coordinates of where the sheep was hunted, estimated age, days taken to carry out the hunt and so forth. The technician also took biological samples for disease analysis.

The horns and skin of the bighorn sheep shot by the hunter at 850 yards are still in the office of the technical team in La Paz. Issuance of the CITES permit for the trophy to be transported across international borders to the US-based hunter could take 3-4 months (SEMARNAT must also be consulted). CITES is a legally binding agreement between governments that works to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals or plants does not threaten the survival of the species. Only Mexico’s bighorn sheep population is listed on CITES Appendix II which covers species that are not necessarily threatened by international trade but that are deemed worthy of a close eye so that they do not slip into the highest category of endangerment, Appendix I. When weighing the permit to send this hunter his trophy they will carefully review, among other things, the report of the UMA technician who accompanied the hunt and took detailed notes on the geographical coordinates of where the sheep was hunted, estimated age, days taken to carry out the hunt and so forth. The technician also took biological samples for disease analysis.

Gabriela, Guillermo and the technical team for the UMAs all note that trophy hunting is extremely controversial in Mexico. Even some of the very officials whose offices support trophy hunting personally speak out against it. The IUCN, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, has long supported sustainable, properly managed trophy hunting in conservation when it provides incentives for people to conserve the trophy species and their habitats. Sacrificing a few for the many is a concept that will never unify humanity, but by the IUCN’s measure – and that of CONABIO, CITES and the UMAs – the bighorn sheep trophy program has been a success in BCS, for the species, its habitat, and for the local communities.

How the permit funds are used:

Del pago que se hace a las UMAS por la venta de los permiso para la caza de borrego cimarron el 70% es entregado a las ejidatarios dueños de las las tierras donde se encuentra la UMA y 30% es dedicado a la conservación, donde se realizan las siguentes actividades:

Actividades de conservación implementadas

Colocación de letreros, puertas de acceso

Placement of signs, gates

Censo aéreo

Aerial Census

Plan de Acción para la Conservación y manejo de las Sierras Borregueras de B.C.S.

(Con apoyo de SEMARNAT)

Limpieza y rehabilitación de aguajes

Cleaning and rehabilitation of Aguajes

Monitoreo y Vigilancia

Monitoring and surveillance

Capacitación

Training courses

Delimitación de las áreas de distribución e identificación de corredores biológicos

Delimitation of the areas of distribution and identification of biological corridors

Identificación de la problemática con la fauna feral

Identification of the problem with feral fauna

Entrega de reportes anuales a SEMARNAT

Activity Report

Construcción de corrales para el manejo de fauna feral

Construction of corrals for feral wildlife management

Programa de manejo de fauna feral

Program implementation of feral animal management

Mejoramiento de hábitat

Improvement of habitat

Diversificación de actividades: ecoturismo, cabañas, aprovechamiento cinegético de otras especies

Diversification of activities: ecotourism, cabins, hunting of other species

Don Cata created a type of corral where he would collect 18 to 20 bulls, put bells on them, then get them to the road where a truck would pick them up, weigh them and deliver them to the Collins family. “I got over 600 bulls like this” recalls Dona Cata. In a masterful piece of understatement about his running skills Don Cata notes, “I was fast.”

Don Cata created a type of corral where he would collect 18 to 20 bulls, put bells on them, then get them to the road where a truck would pick them up, weigh them and deliver them to the Collins family. “I got over 600 bulls like this” recalls Dona Cata. In a masterful piece of understatement about his running skills Don Cata notes, “I was fast.” Then in 1997 a major hurricane hit off the coast of Los Cabos and it rained for 3 days straight. This created an enormous bounty of food and water for the pigs so in the ensuing years their population exploded. “There were so many pigs that they were eating all the grass in the valley of the mountain and really damaging the ecosystem” recalls Don Cata. The Sierra La Laguna Biosphere Reserve park authorities decided that some of the pigs needed to be eradicated so they contracted Don Cata for the job. “Thankfully the pigs prefer terrain that is accessible by horse and mule” the older Don Cata laughingly notes.

Then in 1997 a major hurricane hit off the coast of Los Cabos and it rained for 3 days straight. This created an enormous bounty of food and water for the pigs so in the ensuing years their population exploded. “There were so many pigs that they were eating all the grass in the valley of the mountain and really damaging the ecosystem” recalls Don Cata. The Sierra La Laguna Biosphere Reserve park authorities decided that some of the pigs needed to be eradicated so they contracted Don Cata for the job. “Thankfully the pigs prefer terrain that is accessible by horse and mule” the older Don Cata laughingly notes.

This year, Jason Nengola, Ultimate Safaris’ 2024 Ultimate Guide of the Year, travelled to Baja California, Mexico, for a three-week immersion experience with Todos Santos Eco Adventures. The exchange underscores a shared mission between the two companies: to empower guides, foster cross-cultural conservation practices, and celebrate the ecosystems they passionately protect.

This year, Jason Nengola, Ultimate Safaris’ 2024 Ultimate Guide of the Year, travelled to Baja California, Mexico, for a three-week immersion experience with Todos Santos Eco Adventures. The exchange underscores a shared mission between the two companies: to empower guides, foster cross-cultural conservation practices, and celebrate the ecosystems they passionately protect.

NOS adapted its thinking. They started reaching out to the fishermen through their children by supporting local soccer teams and eventually the fishermen agreed to meet with them. “When we first went into El Manglito we thought we knew everything about fisheries conservation and all we had to do was convince the fishermen” recalls Liliana. “But we soon realized our approach was not working so we started talking in a very different way. And by that I mean we, NOS, stopped talking. We started listening. And it was beautiful how the whole idea of restoration emerged from them.”

NOS adapted its thinking. They started reaching out to the fishermen through their children by supporting local soccer teams and eventually the fishermen agreed to meet with them. “When we first went into El Manglito we thought we knew everything about fisheries conservation and all we had to do was convince the fishermen” recalls Liliana. “But we soon realized our approach was not working so we started talking in a very different way. And by that I mean we, NOS, stopped talking. We started listening. And it was beautiful how the whole idea of restoration emerged from them.” But they were resilient. “The fishermen knew it was possible to bring the callo de hacha back, to restore their original fishing area” says Liliana. “We didn’t know it, but they did.” The fishermen knew where the richest points in the bay were for the scallops and knew what needed to be done. “We had assumed that they were evil fishermen and that we were going to save them. Turns out, they knew exactly how to save themselves.” Thus started the callo de hacha restoration project that took seven years and attracted people from all around the world – biologists, conservationists, impact investors. “Everything was happening as Alejandro and that team had dreamed. It was beautiful.”

But they were resilient. “The fishermen knew it was possible to bring the callo de hacha back, to restore their original fishing area” says Liliana. “We didn’t know it, but they did.” The fishermen knew where the richest points in the bay were for the scallops and knew what needed to be done. “We had assumed that they were evil fishermen and that we were going to save them. Turns out, they knew exactly how to save themselves.” Thus started the callo de hacha restoration project that took seven years and attracted people from all around the world – biologists, conservationists, impact investors. “Everything was happening as Alejandro and that team had dreamed. It was beautiful.” But only once the women showed up. NOS, with the support of key funders, had made the controversial decision to pay the fishermen during the restoration period while fishing was suspended. Some of their wives were not impressed with the results. Martha Garcia, speaking for herself and her friend Araceli Méndez says, “As soon as our husbands started receiving payment for not fishing during the restoration, our dream of transforming El Manglito into a beautiful, healthy community became just a job for them. They lost the dream.” Araceli didn’t think their husbands were performing particularly well at the job either. El Manglito had instituted a surveillance system at the Conchalito scallop banks to keep the poachers out, and the men were approaching the banks by boat. Notes Araceli, “It gets really shallow there so the boats would get stuck in the mud and the men would just end up having shouting matches with the poachers who would always get away with the scallops overland.” Their friend Graciela Olachea designed a new approach. “We could tell where the poachers were accessing the banks by land” continues Araceli, “So me, Graciela, Martha, and several other women started patrolling the land around the banks and scaring off the poachers that way.” The women achieved in 3 months what the men had failed to achieve in 3 years. The poachers were gone. Liliana sighs ruefully, “We should have started with the women.”

But only once the women showed up. NOS, with the support of key funders, had made the controversial decision to pay the fishermen during the restoration period while fishing was suspended. Some of their wives were not impressed with the results. Martha Garcia, speaking for herself and her friend Araceli Méndez says, “As soon as our husbands started receiving payment for not fishing during the restoration, our dream of transforming El Manglito into a beautiful, healthy community became just a job for them. They lost the dream.” Araceli didn’t think their husbands were performing particularly well at the job either. El Manglito had instituted a surveillance system at the Conchalito scallop banks to keep the poachers out, and the men were approaching the banks by boat. Notes Araceli, “It gets really shallow there so the boats would get stuck in the mud and the men would just end up having shouting matches with the poachers who would always get away with the scallops overland.” Their friend Graciela Olachea designed a new approach. “We could tell where the poachers were accessing the banks by land” continues Araceli, “So me, Graciela, Martha, and several other women started patrolling the land around the banks and scaring off the poachers that way.” The women achieved in 3 months what the men had failed to achieve in 3 years. The poachers were gone. Liliana sighs ruefully, “We should have started with the women.” Las Guardianas take turns telling some of their story. “The mangrove area at Conchalito where we ran off the poachers was a disastrous eyesore that served as a drive-through hotel, a drug dealers’ office, and a neighborhood dump” notes Daniela Bareño. “We reclaimed that land for the neighborhood.” Her colleague Claudia Reyes continued. “The first thing we did was push huge stones across the entryway to stop vehicles from entering, then we organized massive trash cleanups in which we got all segments of the neighborhood engaged. We were taking out 3 tons of trash at a time.” Daniela continued, “While we were cleaning the area, a woman came running in who was being pursued by some scary men. Araceli, Marta and I chased those men away. That incident made us realize that women come here because they know that we are women creating a safe space for women.” El Conchalito is now a beautiful public space for the people of La Paz where people come to walk their dogs, go bird watching, and enjoy the mangroves. Rosa Hale, who tracks usage of the area is particularly proud of one statistic, “The number of women using the space has increased by 70% since we started.”

Las Guardianas take turns telling some of their story. “The mangrove area at Conchalito where we ran off the poachers was a disastrous eyesore that served as a drive-through hotel, a drug dealers’ office, and a neighborhood dump” notes Daniela Bareño. “We reclaimed that land for the neighborhood.” Her colleague Claudia Reyes continued. “The first thing we did was push huge stones across the entryway to stop vehicles from entering, then we organized massive trash cleanups in which we got all segments of the neighborhood engaged. We were taking out 3 tons of trash at a time.” Daniela continued, “While we were cleaning the area, a woman came running in who was being pursued by some scary men. Araceli, Marta and I chased those men away. That incident made us realize that women come here because they know that we are women creating a safe space for women.” El Conchalito is now a beautiful public space for the people of La Paz where people come to walk their dogs, go bird watching, and enjoy the mangroves. Rosa Hale, who tracks usage of the area is particularly proud of one statistic, “The number of women using the space has increased by 70% since we started.” Liliana nominated Las Guardianas for a National Geographic grant. They won and received training in birdwatching to further their dream of guiding people on birding trips through the mangroves. Inspired, Araceli pondered why the women never dove, only the men. They all sent letters to the Women Divers Hall of Fame in the US which awarded a scholarship to each Guardiana who wanted to learn to dive. The photo of Araceli, Martha and Claudia diving with the National Geographic flag is now the stuff of legend.

Liliana nominated Las Guardianas for a National Geographic grant. They won and received training in birdwatching to further their dream of guiding people on birding trips through the mangroves. Inspired, Araceli pondered why the women never dove, only the men. They all sent letters to the Women Divers Hall of Fame in the US which awarded a scholarship to each Guardiana who wanted to learn to dive. The photo of Araceli, Martha and Claudia diving with the National Geographic flag is now the stuff of legend. And this is how Las Guardianas get things done. They support each other to pursue their own passions, and they inform the NGOs about what support is most beneficial to them. While there’s scarcely a high school diploma amongst them, Araceli is now the “biologist” and is the first woman oyster farmer in La Paz; Daniela is the “engineer” who is working on restoring the Conchalito mangroves in conjunction with WildCoast; Claudia is the “Professor” who teaches people about El Conchalito and takes courses on sustainable business initiatives; Rosa is the “Secretary” who generates use statistics for the estuary; and Martha is the “lawyer” who negotiates deals and recently got Las Guardianas incorporated as their own legal entity. More importantly, she negotiated the permit for the group to restore the Conchalito mangroves, the first time such a permit has ever been issued in La Paz.

And this is how Las Guardianas get things done. They support each other to pursue their own passions, and they inform the NGOs about what support is most beneficial to them. While there’s scarcely a high school diploma amongst them, Araceli is now the “biologist” and is the first woman oyster farmer in La Paz; Daniela is the “engineer” who is working on restoring the Conchalito mangroves in conjunction with WildCoast; Claudia is the “Professor” who teaches people about El Conchalito and takes courses on sustainable business initiatives; Rosa is the “Secretary” who generates use statistics for the estuary; and Martha is the “lawyer” who negotiates deals and recently got Las Guardianas incorporated as their own legal entity. More importantly, she negotiated the permit for the group to restore the Conchalito mangroves, the first time such a permit has ever been issued in La Paz.

“It was so hot and the terrain was so steep and challenging” recalls La Paz-based bighorn sheep hunting translator Angel Antonio Marquez. “We had to stick to the shadows so the sheep couldn’t see us, making the walking even more difficult. When we were 850 yards from the ram the hunter decided to take the shot. We all thought he was crazy since it was so far and we were not at all surprised when he missed. The bullet went right between that sheep’s legs.” Angel continued, “Now this would have scared away most animals, but there was a female sheep nearby and this male was trying to be macho for her so he just stood there. The hunter got him on the second shot. 850 yards. It is the record for the farthest shot in this area.”

“It was so hot and the terrain was so steep and challenging” recalls La Paz-based bighorn sheep hunting translator Angel Antonio Marquez. “We had to stick to the shadows so the sheep couldn’t see us, making the walking even more difficult. When we were 850 yards from the ram the hunter decided to take the shot. We all thought he was crazy since it was so far and we were not at all surprised when he missed. The bullet went right between that sheep’s legs.” Angel continued, “Now this would have scared away most animals, but there was a female sheep nearby and this male was trying to be macho for her so he just stood there. The hunter got him on the second shot. 850 yards. It is the record for the farthest shot in this area.” The UMAs of BCS pay for a team of technicians to regularly monitor the bighorn sheep population on land, participate in the hunts, and accompany the aerial surveys that are conducted every three years. The technicians are extremely clear in their minds about the value of the trophy program. “If it were not for the economic power of the trophy permits, the Bighorn sheep population would almost certainly have been decimated by now and the ejidos would have sold off most of the land” observes Ing. Antia Duarte Camacho, Field Technician of de Ejido San Jose de la Noria and Ejido Lic. Alfredo V. Bonfil. “The bighorn sheep habitat is all along the Sea of Cortez, making that land extremely valuable.” Her colleague Ecologist Miguel Angel Aguilar Juárez, Field Technician of Ejidos Ley Federal de Aguas 1, 2 and 3 adds, “By 2014 the ejidos, many of which had been impoverished, were really starting to understand the huge, sustained, economic lift flowing from the trophy program. They developed a deep appreciation for the value of the land that they own and the sheep that inhabit it. That is when they all really started working together to make the program work as a whole in BCS. Bighorn sheep move seasonally across a vast territory so corridors are important. Income from bighorn sheep hunting started motivating the ejidos to work together to maintain these huge areas with no other human activities, including the raising of livestock.” CONABIO points to the resulting large-scale habitat conservation and improved connectivity as a major achievement of the trophy hunting program.

The UMAs of BCS pay for a team of technicians to regularly monitor the bighorn sheep population on land, participate in the hunts, and accompany the aerial surveys that are conducted every three years. The technicians are extremely clear in their minds about the value of the trophy program. “If it were not for the economic power of the trophy permits, the Bighorn sheep population would almost certainly have been decimated by now and the ejidos would have sold off most of the land” observes Ing. Antia Duarte Camacho, Field Technician of de Ejido San Jose de la Noria and Ejido Lic. Alfredo V. Bonfil. “The bighorn sheep habitat is all along the Sea of Cortez, making that land extremely valuable.” Her colleague Ecologist Miguel Angel Aguilar Juárez, Field Technician of Ejidos Ley Federal de Aguas 1, 2 and 3 adds, “By 2014 the ejidos, many of which had been impoverished, were really starting to understand the huge, sustained, economic lift flowing from the trophy program. They developed a deep appreciation for the value of the land that they own and the sheep that inhabit it. That is when they all really started working together to make the program work as a whole in BCS. Bighorn sheep move seasonally across a vast territory so corridors are important. Income from bighorn sheep hunting started motivating the ejidos to work together to maintain these huge areas with no other human activities, including the raising of livestock.” CONABIO points to the resulting large-scale habitat conservation and improved connectivity as a major achievement of the trophy hunting program. The horns and skin of the bighorn sheep shot by the hunter at 850 yards are still in the office of the technical team in La Paz. Issuance of the CITES permit for the trophy to be transported across international borders to the US-based hunter could take 3-4 months (SEMARNAT must also be consulted). CITES is a legally binding agreement between governments that works to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals or plants does not threaten the survival of the species. Only Mexico’s bighorn sheep population is listed on CITES Appendix II which covers species that are not necessarily threatened by international trade but that are deemed worthy of a close eye so that they do not slip into the highest category of endangerment, Appendix I. When weighing the permit to send this hunter his trophy they will carefully review, among other things, the report of the UMA technician who accompanied the hunt and took detailed notes on the geographical coordinates of where the sheep was hunted, estimated age, days taken to carry out the hunt and so forth. The technician also took biological samples for disease analysis.

The horns and skin of the bighorn sheep shot by the hunter at 850 yards are still in the office of the technical team in La Paz. Issuance of the CITES permit for the trophy to be transported across international borders to the US-based hunter could take 3-4 months (SEMARNAT must also be consulted). CITES is a legally binding agreement between governments that works to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals or plants does not threaten the survival of the species. Only Mexico’s bighorn sheep population is listed on CITES Appendix II which covers species that are not necessarily threatened by international trade but that are deemed worthy of a close eye so that they do not slip into the highest category of endangerment, Appendix I. When weighing the permit to send this hunter his trophy they will carefully review, among other things, the report of the UMA technician who accompanied the hunt and took detailed notes on the geographical coordinates of where the sheep was hunted, estimated age, days taken to carry out the hunt and so forth. The technician also took biological samples for disease analysis.