by Bryan Jáuregui | Adventure, Culture, Ranchero Culture

by Bryan Jáuregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures

This article was originally published in Janice Kinne’s Journal del Pacifico

The American Cowboy is the quintessential symbol of what made America great: strong character, diverse skills, creative problem solving, resilient nature and beef on the table. The iconic cowboys loved their whiskey, played their harmonicas, and sported nicknames like Cactus Pete, Deadeye Jake and Kid Curry. But If you look under the buckskin a bit you’ll find that the original American cowboys likely preferred tequila, played bass fiddles, and had nicknames like El Coyote, Güero de las Canoas and Dos Santos Biel. And that’s exactly why Meg Glaser, Artistic Director of the Western Folklife Center in Elko, Nevada invited 5 Baja California Sur vaqueros (cowboys) to be the guests of honor at the 31st National Cowboy Poetry Gathering: they are the living link between the Spanish missionary soldiers that came to Baja California 300 years ago, and the American buckaroo. Yep, as surely as the Statue of Liberty came from France, and the melody of the Star-Spangled Banner came from England, the American Cowboy came from Mexico. Juan Wayne would have been a more apt screen name for the Duke.

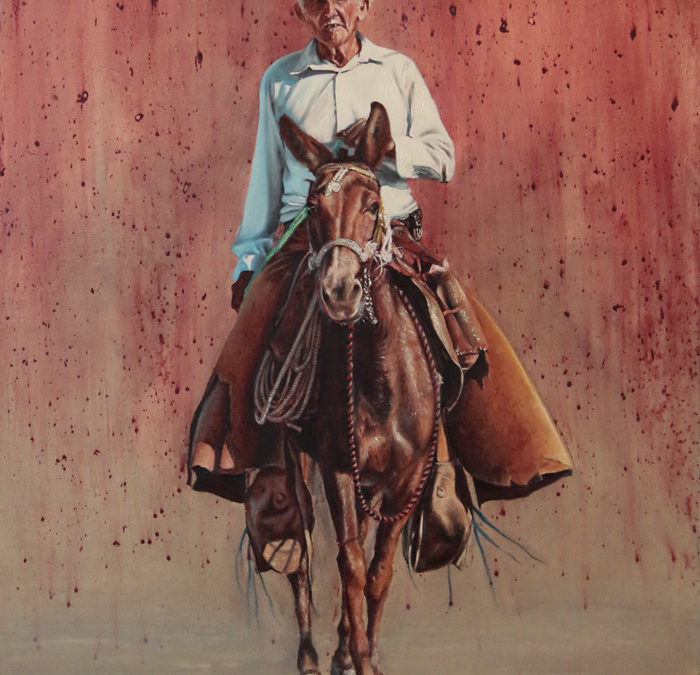

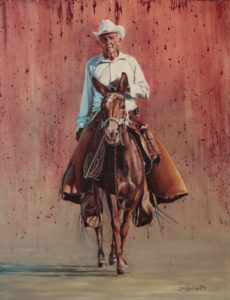

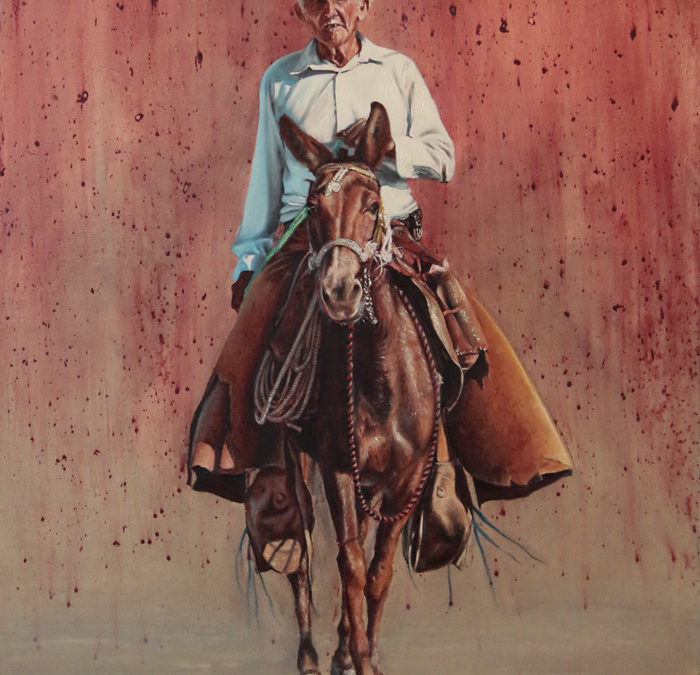

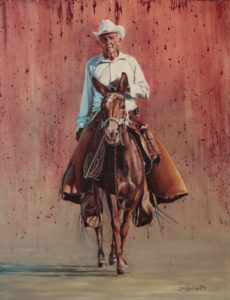

Don Jose y La Pancha. Painting by Carlos Cesar Diaz Castro

The Western Folklife Center (WFC) focuses on making connections with other horse and ranching cultures from around the world. They have hosted cowboys from the far-flung corners of the earth, including Mongolia, Hungary and Brazil, but nothing they had ever done prepared them for the challenge of hosting the vaqueros of Baja California Sur. Says Meg, “The BCS vaqueros live almost completely off the grid so they didn’t have passports, US visas, or even email access. It was incredibly challenging to get these men who live on roadless ranches, some of whom must ride 6 hours on mules to get to the nearest highway, from Baja to Nevada, but together with the great Baja team we did it and it was one of our most successful programs ever. Many of our buckaroos in Nevada and other parts of the west are pretty well versed on the history and the connection between the American cowboy and the Mexican vaquero, but very few of us realized that it was such a vibrant living culture. It was a real eye opener for all of us.”

Of course back in the day both Nevada and Baja were part of the Spanish California Provinces (Nevada in Alta or Upper California and present day BCS in Baja or Lower California) and cowboys and cattle – imported from Spain to satisfy the conquerors’ demand for beef – flowed freely throughout the region. In fact, the regions were so integrated culturally and linguistically that it wasn’t until the 1960s that people from Baja California were required to have a passport and visa to travel to the USA. The lingua franca of cowboys demonstrates the cultural link between the two Californias: “buckaroo” is the Americanization of the word “vaquero”, “chaps” comes from the Spanish word chaparreras, or leather leggings, “rodeo” comes from the Spanish word rodear, to surround, and “mustang” comes from the Spanish word mostrenco. The modern livestock industry in the USA continues to thrive on early Mexican techniques for handling cattle including branding, saddle cinching and using a hand-braided lariat – from the Spanish la reata – to rope cattle.

Chema with his guitar in the Sierras.Photo courtesy of Saddling South

But now there is most definitely a border, and crossing it was a tremendous experience for the whole team. Says vaquero Jose Maria Arce Arce, who goes by Chema, “Just imagine. I had to ride a mule for several hours out of the Sierras as part of the journey to the airport, then suddenly I was on a huge airplane and we flew over my ranch – I recognized it immediately and was amazed to see it from the air. This trip was my first time on an airplane and my first time in such a nice hotel. Imagine a horse that is accustomed to poor grazing areas then he’s put in a green pasture. That is what it felt like to me.” Trudi Angell has been Chema’s friend and business associate in the Sierra San Francisco since 2005, and she was the main organizer of the trip. The vaqueros nicknamed her “La Caponera” or “the bell-mare” of the trip: the one to follow. She sat next to Chema’s cousin, Bonifacio, or “Boni” on the first flight. “His eyes lit up like a kid as he turned around at lift-off and practically shouted “ ‘Chinga! The cars all look like ants!’ Forty minutes later when we flew over the Sierra San Francisco, Chema and Ricardo (Chema’s son who’s known as Teté) were pressed to the window pane and were practically beside themselves when they saw their ranch from the sky. It was a wonderful experience.”

Chema, Teté and Boni are Los Regionales de la Sierra, a musical group that plays traditional ranchero music from the northwest of Mexico, much of it resonant of eras long gone by. Chema plays accordion and guitar, Boni plays bajo sextoand accordion, and Tetéplays the northern ranchero bass fiddle. In Elko they performed often at schools, juvenile facilities and the Western Folklife Center itself, and were accompanied by singers Damiana and Duna Conde, daughters of the renowned Baja California Sur musician, comedian and political satirist Raul Conde. The crowds and other musicians simply couldn’t get enough of the group, and they were feted everywhere they went. Even Sourdough Slim, an acclaimed western singer who regularly plays the Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall Folk Festival circuit invited the vaqueros to jam with him at the historic Pioneer Bar one evening. Observes Meg, “They were a smash sensation.”

Carlos’ stand up paintings of Boni, Chema and Tete. Part of the BCS exhibit.

The great reception to their musical skills wasmatched only by the tremendous enthusiasm for their skills as ranchers and craftsmen. Chema, Dario Higuera Meza and the other vaqueros met with American cowboys and shared information on ranching lifestyles, including working and breeding donkeys and horses. Says Chema of his American counterparts, “They are the same people that I am. I completely identified with them… the only difference is in the way they dance!” Dario, who is one of the few artisans left in BCS who knows how to create traditional ranch crafts using the old Baja California methods (he received an honorary degree from the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur in recognition of his unparalleled skills and contribution to BCS culture), gave daily demonstrations on horsehair rope making and leather braiding, and in particular bonded with several native American families over different methods of tanning and spinning rope. They were so enthralled with Dario they invited him to a Navajo festival. Chema’s nephew, Juan Gabriel Arce Arce – nicknamed Biel – gave daily demonstrations on leatherworking and other traditional ranch skills. Biel consistently wins the top prize at state-wide leatherworking contests.A traditionally tanned leather trunk that he made with ornately woven edges and beautiful hand tooling was purchased by a Basque ranching family from Elko for US$5,000.

Biel’s Chest

McKenzie Campbell, one of the people responsible for getting the vaqueros to Elko, is the founder of Living Roots, a non-profit which helps BCS ranch families capitalize on their skills. At the request of the WFC gift shop, she made sure that the group brought many leatherwork pieces made by Teté, Dario, Biel and other ranchers, includingpolainas (leather gators), miniature vaquero saddles, belts and teguas (riding shoes). McKenzie also brought other BCS ranchero crafts including embroidered purses and bags, as well as tepetes, rag rugs that women make with scraps of cloth. It allsold like hot cakes in the gift shop.

The vaqueros are direct descendants of soldiers imported by the Jesuit missionaries in the 1700s. Recruited as part of a deal with the king of Spain that gave the Jesuits administrative autonomy in Baja California in return for protecting the territory from pirates, these “soldiers” were in fact largely people from Moorish Spain who had the excellent ranching and agricultural skills the Jesuits needed to develop their missions. They became known as the “soldiers of leather” to distinguish them from fighting “soldiers of metal”. When the Jesuits were subsequently kicked out of Baja, the “soldiers of leather” who worked the missions were given the lands by administrative fiat and from that point on Baja ranchero culture flourished. Largely forgotten by the rest of Mexico for several

Fermin Building the Rancho Exhibit

generations and isolated by geography, the architecture, ranch tools, farm implements and cookware of BCS ranches remains to this day very similar to that developed by their Spanish forbears 300 years ago. “The BCS rancheros are a piece of the past that has survived until today” says Fermín Reygadas, a professor of Alternative Tourism at the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur who has worked with Baja Californiarancheros for over 30 years.

Fermín, who counts ranchers as some of his best friends in Baja, envisioned and happily executed the task of recreating a typical ranch dwelling with an hoja (palm-frond) roof and palo d’arco walls for the exhibit at the WFC. Working with La Paz artist Carlos César Diaz Castro in Elko a full month before the vaqueros arrived, Fermíncreated a truly astounding exhibit which everyone agrees captures the heart and soul of BCS ranchero life. Says Trudi, “The BCS exhibit was left up for 8 months and a woman from the WFC sent me a special note to say that the local folks from Elko came again and again to see the exhibit, bringing visiting friends and family. They had never seen this type of reaction to an exhibit before.”

Carlos Painting Tete. Photo by Karla Fernanda Amao

The whole project got started when Rick Knight, a professor from Colorado State University and board member of the WFC, went on a mule trip with Trudi’scompany,Saddling South, in the Sierras. Chema was their guide at the Sierra San Francisco rock art sites, and he and his family entertained the group around the campfire at night. Rick informed Meg Glaser of the incredible experience he had had and in 2012 Meg came down to see it for herself. She knew right away she had to get the vaqueros to Elko.Three years later – which included intensive months of effort by Trudi in the quest for Mexican passports and US visas for 5 people who live almost completely outside the system (letters to the US Consulate from Nevada Senator Harry Reid, the BCS State Board of Tourism, the Western Folklife Center and several others all had to be obtained) – the group was in Elko. The connections made between people and cultures moved them all. Says Chema, “The best part is that we went so far and met people we had become friends with at the caves in the Sierras.” Says Meg, “The best part is that the social connections extend far beyond Elko and many people have already gone to Baja Sur to visit the Sierras and learn more about the vaquero culture.” Says Fermín, “The best part was watching the vaqueros bond with the US ranchers discussing knots and ropes, sharing ideas and experiences. It really showed how connected we all are.”For his part, Dario, who is not one of the musicians, had so much fun that he wrote a song about the whole experience.

Elko Group Portrait Back Row, Left to Right: Karla Fernanda Amao (Carlos’s wife), Carlos Cesar Diaz Castro, Dune Conde, Fermin Reygadas Dahl, McKenzie Campbell, Chema (Jose Maria Arce Arce), Damiana Conde, Ricardo Arce Arce (Tete), Juan Gabrial Arce Arce (Biel), Bonifacio Arce Arce (Boni). Seated Front Row: Trudi Angell, Dario Higuera Meza, Teodora Montes Botham, Meg Glaser. Photo courtesy of Western Folklife Center.

Concludes Chema, “I never had a childhood because I’ve worked since I was a little boy. I now feel very proud that people know me and our life here at the ranch, both through the movie Corazon Vaquero and our trip to Elko. We represented the Baja California vaqueros to the cowboys of the US, and they really respect all the things we can do. It was a beautiful experience. But I’m still the same humble

Chema and his grandaughter Azu. Photo courtesy of Saddling South

rancher I have always been and I haven’t changed my way of life. All of my grandchildren are becoming ranchers and I’m very pleased about that.” Fermín calls the vaqueros of BCS “an oasis of common sense humans.” Maybe Chema’s grandkids will be the next generation of Cowboy Ambassadors, connecting US cowboys to their living roots in Baja California Sur. Could there be another ride for the bell-mare? Possibly. Trudi says her first thought when she woke up after the trip to Elko was, “We have to take this show on the road!”

© Copyright Sergio and Bryan Jauregui, Casa Payaso S de RL de CV, 2016

by Bryan Jáuregui | Adventure, Education, Wildlife

by Bryan Jauregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures

This article first appeared in Janice Kinne’s Journal del Pacifico

If they had a World Championship for Insult Hurling, China’s entry of “Son of a Turtle!” may not seem like obvious prize material. But a review of sea turtle reproductive habits reveals why the insult might be a contender: A female sea turtle will mate with several males prior to nesting season, storing the sperm of all her paramours in oviducts separate from her eggs for extended periods of time – sometimes years. When the time is right for nesting, her body will allow the sperm to fertilize the eggs, resulting in what scientists like to call “multiple paternity” for her offspring. In other words, little baby sea turtles have no idea who their daddies are. Get it?

Loggerhead Turtle. Photo by Colin Ruggiero

(more…)

by Bryan Jáuregui | Adventure, Sports

by Bryan Jáuregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures

This article first appeared in Janice Kinne’s Journal del Pacifico

She’s been free diving since before she could walk, but every time she gets in the water for a competition she reflects on the old nightmare: She’s swimming peacefully at the shore when the ocean suddenly starts retracting away from the beach at great speed like it does before a tsunami. She’s caught in the enormous power of the angry water, completely out of control. She’s filled with dread of the cold and the dark, terrified of being so absolutely alone.

“But competitive free diving is at least 70% mental” says Mexican free diving  champion Estrella Navarro Holm. “And it was free diving that finally put that old nightmare to rest. In competition they allow us a few minutes on the rope at the surface before the dive, and I use that time to do my deep breathing, face any fears I may have, and relax into the dive. Once the count reaches zero, the rules allow only 30 seconds to get your face in the water, so you have to be ready.” Ready to dive 70 meters (230 feet) into the black of the ocean with no oxygen, no light, no friends, just the air in your lungs and your wet suit to protect you? Fear is the only rational response. “Yet”, says Estrella, “once my face is in the water the training kicks in and my diving reflex is activated. My whole system has a physiological response to my mental state and I am completely prepared to go. The first few meters are hard because my body is heavy and buoyant with air, and I have to really work to get down. But then at about 30 meters the free fall starts. It’s as if the wet suit and my skin fall away, and the water in my body merges with the water of the ocean. Each molecule of water feels very intense. It’s like flying, but in slow motion. The free fall is the most beautiful, spiritual experience – it’s what makes people free diving junkies.” Knew there had to be a payoff.

champion Estrella Navarro Holm. “And it was free diving that finally put that old nightmare to rest. In competition they allow us a few minutes on the rope at the surface before the dive, and I use that time to do my deep breathing, face any fears I may have, and relax into the dive. Once the count reaches zero, the rules allow only 30 seconds to get your face in the water, so you have to be ready.” Ready to dive 70 meters (230 feet) into the black of the ocean with no oxygen, no light, no friends, just the air in your lungs and your wet suit to protect you? Fear is the only rational response. “Yet”, says Estrella, “once my face is in the water the training kicks in and my diving reflex is activated. My whole system has a physiological response to my mental state and I am completely prepared to go. The first few meters are hard because my body is heavy and buoyant with air, and I have to really work to get down. But then at about 30 meters the free fall starts. It’s as if the wet suit and my skin fall away, and the water in my body merges with the water of the ocean. Each molecule of water feels very intense. It’s like flying, but in slow motion. The free fall is the most beautiful, spiritual experience – it’s what makes people free diving junkies.” Knew there had to be a payoff.

And that payoff has paid off big time for Estrella. The La Paz native has broken the  Mexican national free diving record 21 times, she was the first Mexican on the medal podium in a free diving world championship, and she’s the first woman in Latin America to medal in the discipline of constant weight no fins. And unlike most world champion athletes, she didn’t enter her first major competition until she was 24. This gave her the time to earn a degree in marine biology from the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur (UABCS) in La Paz, widely acknowledged as one of the best marine biology programs in the country. And she’s using that degree to pursue her other great passion in life, ocean conservation. Among other accomplishments, she is co-author of a paper titled Global Economic Value of Shark Ecotourism: Implications for Conservation, that appeared in Oryx, The International Journal of Conservation, published by Cambridge University Press. Yes, the one in England.

Mexican national free diving record 21 times, she was the first Mexican on the medal podium in a free diving world championship, and she’s the first woman in Latin America to medal in the discipline of constant weight no fins. And unlike most world champion athletes, she didn’t enter her first major competition until she was 24. This gave her the time to earn a degree in marine biology from the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur (UABCS) in La Paz, widely acknowledged as one of the best marine biology programs in the country. And she’s using that degree to pursue her other great passion in life, ocean conservation. Among other accomplishments, she is co-author of a paper titled Global Economic Value of Shark Ecotourism: Implications for Conservation, that appeared in Oryx, The International Journal of Conservation, published by Cambridge University Press. Yes, the one in England.

It is often the case in life that we don’t fully appreciate what we have at home until we travel elsewhere. And as Estrella traveled the waters of the globe for competitions, she found that her fellow athletes scarcely believed her when she described the riches of the Sea of Cortez, marveling – some skeptically – when she told them about diving with sea turtles, sea lions, whale sharks, whales, dolphins and more. Their wonderment (incredulity) gave her an idea for combining her passions: invite the best free diving athletes in the world to La Paz to share the wonders of the Sea of Cortez and, at the same time, promote ocean conservation. Says Estrella, “I sent out 250 personal invitations via Facebook to my free diving friends, and I was so thrilled that 24 of the best athletes in the world accepted the invitation to compete in our program, Big Blue. But I was even more excited that they took up the call to be ocean ambassadors, to return to their home countries and promote strong ocean conservation measures. This is really the success of Big Blue.”

Indeed, as part of the Big Blue program in November 2015, Estrella, working in coordination with the tourism board of Baja California Sur, organized a conference on  ocean conservation where she presented the shark research in which she and her co-authors demonstrated that shark ecotourism around the world currently generates US$314 million a year and supports 10,000 jobs – a vastly higher and more sustainable number than those associated with shark landings each year. That is to say, as is generally the case when speaking of wild flora and fauna, the living, breathing resources of the world are worth more to mankind alive than dead.

ocean conservation where she presented the shark research in which she and her co-authors demonstrated that shark ecotourism around the world currently generates US$314 million a year and supports 10,000 jobs – a vastly higher and more sustainable number than those associated with shark landings each year. That is to say, as is generally the case when speaking of wild flora and fauna, the living, breathing resources of the world are worth more to mankind alive than dead.

Estrella wants to keep bringing that message to the world, and plans to make Big Blue an annual event in La Paz, her home town and a great staging area for exploring the Sea of Cortez. Estrella is part of a growing cadre of world class athletes that grew up in La Paz and the Sea of Cortez (Mexican board diving champion and Olympian Paola Espinosa’s dad was actually Estrella’s competitive swimming trainer when she was a little girl, and the two champions remain friends) and their love for their home town is helping to fuel growing interest in La Paz as a destination for top competitions in many sports including stand up paddle boarding, water polo, swimming and, of course, diving.

But unlike her fellow champions in other sports, Estrella doesn’t worry so much about the  march of time. One of the greatest female free divers of all time, Natalia Molchanova, became the first woman to dive 100 meters (328 feet) at the age of 44, and continued to dominate the sport for another decade. (Her son Alexey swept the Big Blue competition in La Paz and is the reigning world champion.) So that means that for the foreseeable future, Estrella can continue to both compete in oceans around the world, and create the knowledge and ambassadors to help protect them. Saving it all for the generations to come. That’s what truly makes the champion Estrella Navarro Holm the Star of the Sea of Cortez.

march of time. One of the greatest female free divers of all time, Natalia Molchanova, became the first woman to dive 100 meters (328 feet) at the age of 44, and continued to dominate the sport for another decade. (Her son Alexey swept the Big Blue competition in La Paz and is the reigning world champion.) So that means that for the foreseeable future, Estrella can continue to both compete in oceans around the world, and create the knowledge and ambassadors to help protect them. Saving it all for the generations to come. That’s what truly makes the champion Estrella Navarro Holm the Star of the Sea of Cortez.

To learn more about Estrella and Big Blue please visit:

www.estrellanavarro.com

www.bigblue.com.mx

by Bryan Jáuregui | Adventure, Culture, Wildlife

by Bryan Jáuregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures

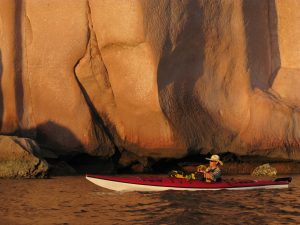

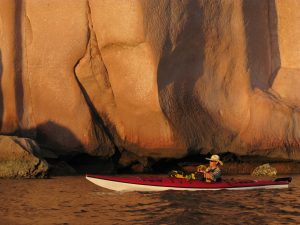

Espiritu Santo photo by Carlos Gajon

If famed aviator Charles Lindbergh had not fallen in love with the daughter of the US Ambassador to Mexico, the story of Isla Espiritu Santo might be just another sad tale of extraordinary natural beauty undone. But the courtship of his future wife in Mexico instilled in Lindbergh a lasting affection for the country. So when in 1973 his friend and fellow conservationist George Lindsey invited him on a scientific exploration of the Sea of Cortez, Lindbergh jumped at the chance. The two men and their scientific team wended their way through numerous islands between Bahia de Los Angeles and La Paz, ultimately arriving at Espiritu Santo. Lindbergh was enthralled. The islands made such an enormous impression on him that during a trip to Mexico City a few months later, Lindbergh requested a meeting with the president of Mexico to discuss protecting what he now considered one of the most beautiful areas on the planet, the Sea of Cortez. Four years later the Mexican government issued a decree establishing 898 islands of the Sea of Cortez a Flora and Fauna Protection Area (Zona de Reserva Natural y Refugio de Aves Migratorias y de la Fauna Silvestre). George Lindsey, then the Director of the San Diego Natural History Museum, strongly believes that Lindbergh’s intervention helped to create the governmental awareness needed to get the decree enacted. It was a good beginning.

Espiritu Santo photo by Cabo Rockwell

Around the same time as Lindbergh’s transformational trip to Baja, a former Grand Canyon river guide named Tim Means was setting up the first major ecotourism company in La Paz, Baja Expeditions. Means’ business thrived as word of Baja’s remarkable flora and fauna spread, and demand grew for access to the natural wonders that the area’s remote location had kept pristine long after the west coast of the US had been heavily developed. But conservation-minded eco adventurers were not the only ones attracted to the area, and by the 1990s the pressure on Isla Espiritu Santo was intense: a real estate developer wanted to create a resort casino on the island. From the outside it seemed absurd that a casino had even the remotest possibility of being approved in a natural protected area, but Mexico’s traditionally lax approach to conservation enforcement afforded the developer optimism.

Espiritu Santo photo by Craig Ligibel

While most of the islands in the Sea of Cortez were federal lands, a few were privately owned, and Espiritu Santo was owned by an ejido. Ejidos, created as part of Mexico’s land reform movement after the Revolution of 1910, are rural collectives of people who own property communally. Traditionally ejidos were not allowed to sell their property, but the constitutional obstructions to ejido land sales were removed in 1992, and the ejido owners of Espiritu Santo lost little time in taking advantage of this new freedom. By 1997 they had sub-divided 90 hectares around Bonanza Beach into 36 lots and were selling them off. Cabins were actually constructed on some of the lots, but in a move that would have made Lindbergh proud, a federal judge deemed them illegal under the 1978 decree and they were torn down. But the real estate developer who owned some of the properties was pushing hard on his casino proposal. Tim Means was prepared to push back.

Means started his onslaught by personally buying two properties smack in the middle of the developer’s proposed casino area. This immediately diminished the attractiveness of the project for the developer, and inclined him towards negotiation. Means then enlisted the aid of leading Mexican businessmen in the area, who retained and paid for the law firm that was ultimately able to arrange the buy out the developer and all but one of the remaining properties for sale on Bonanza Beach. This all took a great deal of time and maneuvering, but Means and his team persevered. All the properties they bought were donated to the federal government.

Espiritu Santo photo by Carlos Gajon

When the immediate threat of the casino was neutralized, Means and a coalition of conservationists were able to put together a deal to purchase the rest of the island, which they bought from the ejido for US$3.3 million. Their subsequent donation of Espiritu Santo to the nation is commemorated by a famous sculpture of a dove on the malecon in La Paz.

The purchase structure that resulted in Espiritu Santo’s conservation in perpetuity demonstrates the power of collaboration among a diverse group of constituents when fighting to preserve wilderness areas: about one third of the money came from Mexican funders, another third from American funders via the Nature Conservancy, and the rest through an anonymous gift to the World Wildlife Fund. The David and Lucille Packard Foundation then donated US$1.5 million towards the future management of Espiritu Santo. This type of international cooperation set the stage for future and ongoing battles against mega-developments elsewhere in Baja California Sur. As a direct result of Means’ successful activism, Espiritu Santo and 244 other islands in the Sea of Cortez were subsequently named a World Heritage Site in 2005.

But none of this would have happened without the will of the Mexican people. As a result of colonial rule, the Mexican citizenry traditionally felt they had no voice in government, so agitation for change was not a big feature of public life. But in the 1970s this started to change, most notably in the environmental arena, and Mexicans began to create organizations committed to protecting the country’s immense natural resources. This process lead to the creation of the Secretaria de Desarollo Urbano y Ecologia (Secretary of Urban Development and Ecology) in 1983, and in 1987 the general law of ecology and natural resources. One of the early successes of all this effort was the 1988 declaration of the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve in the states of Mexico and Michoacan.

Worthy of Protection. Photo by Carlos Gajon.

The people of Mexico in general, and of Baja California Sur in particular, are now intently focused on protecting their natural heritage. In Baja California Sur residents have banded together in recent years to defeat mega-developments in Balandra Bay, El Mogote and Cabo Pulmo, using the reach and resources of both local and international NGOs to aid their cause (See our blog post Conserving the Beauty of Baja). Public outrage and grassroots campaigning have stymied the efforts of companies seeking to operate open-pit gold mining companies in the Sierra de la Laguna Mountains. Like Lindbergh and his nonstop solo flight across the Atlantic, they are succeeding against considerable odds. Like Tim Means and his environmental coalitions, they are hunkered down and ready for the long haul. As the great conservationist Teddy Roosevelt once said, “Great thoughts speak only to the thoughtful mind, but great actions speak to all mankind.” The protection of Isla Espiritu Santo and the islands of the Sea of Cortez wrought by Tim Means and his coalition will speak to the world for generations to come.

Sources: Two excellent books and Tim Means provided the source material for this article. The books are Isla Espiritu Santo: Evolución, rescate y conservación by Exequiel Ezcurra, Harumi Fujita, Enrique Hambleton and Rodolfo Garrio; and Wildlands Philanthropy: The Great American Tradition with essays by Tom Butler and photographs by Antonio Vizcaino.

Todos Santos Eco Adventures operates a tent camp on Isla Espiritu Santo from which visitors can explore the wild natural beauty of the island and the Sea of Cortez.

Why do we care about Espiritu Santo and other areas of Mexico?

There are over 200 countries in the world today but only 12 of them can claim to be “mega-diverse”. A country is considered mega-diverse if it has between 60% and 70% of the total biodiversity of the planet, and Mexico is one of only 3 such countries with coastlines on both the Atlantic and Pacific (the United States and Colombia are the other two). Mexican government sources indicate that Mexico’s global ranks for biodiversity are as follows:

- Reptiles: #2

- Mammals: #3

- Amphibians: #5

- Vascular plants: #5

- Birds: #8

That’s something worth bragging about – and protecting!

This article was first published in Janice Kinne’s Journal del Pacifico

© Copyright Sergio and Bryan Jauregui, Casa Payaso S de RL de CV, 2015

by Bryan Jáuregui | Adventure, Education, Wildlife

by Bryan Jáuregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures

If science had all the answers, poets and dreamers would be out of a job. So when scientists tell us that they’re not really sure why humpback males sing – and it is only the males that sing – then it’s up to the rest of us to look at the evidence and help science along. And here’s what the evidence shows us. Like traditional mariachis, all-male college a capela groups, and the Rat Pack, humpback whales in Baja clearly understand that singing, particularly with the harmonious help of your mates, is the best way to get the girl. Now some scientists theorize that humpback males are singing only as a type of echolocation exercise of the type used by their dolphin cousins, a way to map out the world around them. This certainly

Humpback Happiness. Photo by Erika Peterman

may be true – because how else are they going to find the girls? But that really doesn’t explain why some humpback whale songs are several hours long and, according to the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, grammatically complex and loaded with information. Like a ballad. Or why sexually immature young males join their virile older brothers in song. Like frat boys with their pledges beneath a sorority girl’s window. Or why all the males in one region will congregate in an arena and sing the same song. Like a boy-band in an outdoor stadium. Or why a male escorting a female and her calf will sing. Like a lullaby. These are all great mysteries that the poets are currently best equipped to ponder, but they don’t begin to touch on the greatest mystery of all – how does the female humpback decide which singer is worthy of her affections? Science presently has no answer, but maybe this is why Elvis always sang alone.

This article was originally published in Janice Kinne’s Journal del Pacifico

© Copyright Sergio and Bryan Jáuregui, Casa Payaso S de RL de CV, 2014

by Bryan Jáuregui | Adventure, Education, Travel Industry, Wildlife

by Todos Santos Eco Adventures

This article was first published in Janice Kinne’s Journal del Pacifico.

Marine mammals know how to get the love. Fish, not so much. You post a picture of a sea lion or a dolphin on Facebook, and you’re likely to get comments about cuteness, playfulness, intelligence – the emotion you feel when it looks you in the eye. You post a picture of a sea bass or a dorado on Facebook, and you’re likely to get comments about dinner, seasoning, grilling techniques – apparently fish giving us the fisheye doesn’t tug at our heartstrings.

Manta Ray Eye Photo by Kaia Thomson

But there is one fish that no less an authority on charisma than businessman Richard Branson calls “one of the most charismatic creatures in the ocean”, and that is the elegant, enormous, manta ray. With the largest brain-to-body ratio of all elasmobranchs*, the manta ray is one of the most intelligent fish in the sea. Making that brain function well is a system of blood vessels that envelope the manta’s braincase, keeping the brain warmer than the surrounding tissue. A big, warm brain fosters intelligence, intelligence fosters curiosity, and curiosity causes manta rays to interact with human beings in the water. It’s an incredible thrill.

Manta rays are magnificent creatures to behold. It’s not just that they’re huge: they typically reach a width of 22 feet (7 meters) and a weight of over 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg); and it’s not just that they’re prehistoric-looking: they have cephalic fins on either side of their heads to direct food, which look like horns when furled; it’s just that they’re so darn cool: they look like stealth bombers in the sea, yet move that remarkable bulk with utter grace, using their massive triangular wings (pectoral fins) to fly through the sea, exuding the glide and flow of an eagle in flight. So when you realize that this fish that seems straight out of myth is turning in patterns with you, engaging with you, and – like any good dance partner – making direct (fish) eye contact with you, it, well, tugs at your heartstrings.

Manta Ray Coming to Visit Photo by Kaia Thomson

But some people still just see dinner. Despite the fact that fishing for oceanic manta rays was banned in Mexico in 2007, and that the possession and trade of all mantas and mobulids in Mexican waters is prohibited by law, you can walk into local markets in many Baja towns and find stacks of dried and salted rays for sale. They’re considered an excellent, affordable source of protein. On a global scale the problem is more menacing. Across the tropics they inhabit, mantas are now being killed for their gill rakers, the cleansing plates that filter their food from the ocean. Manta and mobula gill rakers are the latest snake oil cure-all in China, touted as a remedy that cleanses the body of everything from gout to cancer. The organization Manta Ray of Hope, which is acting to protect manta rays from this trade, estimates that the annual gill raker trade volume is 61,000 to 80,000 kilograms (135,000 to 176,000 pounds), with an estimated value of US$11.3 million.

But businessman Richard Branson, who is campaigning for manta ray protection, points out that “while the gills are valuable, the trade is also robbing local economies of [the mantas], which could draw millions of dollars each year for those communities.” In fact, Manta Ray of Hope estimates that manta and mobula ray tourism has an estimated annual value of over US$100 million per year, a far more compelling number than the $11 million currently enjoyed by the gill raker trade. If enough awareness is raised and policy makers (and policy enforcers) act quickly enough, there is still time to staunch what many fear could otherwise be the depletion of the global manta ray population.

Manta Ray Photo by Kaia Thomson

And in Baja California Sur we know the pure joy of having the mantas and mobulas as neighbors. Many days from the Pacific beach it is possible to see the mobula rays skipping along the water, making that distinctive flap-flap-flapping sound as they soar through the air and hit the water repeatedly. And in the Sea of Cortez we’re starting to see a return of the giant manta rays, with a large number of sightings over the last several months. So if you’re in Baja, take the time out to go engage with these remarkable creatures in their natural habitat, and let their charm work itself on you. Once you get to know them, you’ll definitely be joining Richard Branson in giving the gill raker traders the old fisheye.

*Elasmobranchs are in the Class Elasmobranchii, which covers cartilaginous fishes such as sharks, rays and skates.

Manta Ray Fun Facts:

- Manta is the Spanish word for blanket, an apt description of the manta ray shape

- Like their shark cousins, the manta’s skin is covered with dermal denticals – sort of modified teeth that are covered with hard enamel. These are packed tightly together with the tips facing backwards. Not only do they help in protecting the animals from predators, they also aid in hydrodynamics. Manta skin is also covered in a type of mucus which helps protect it from parasites and infection.

- Manta rays have terminal mouths strategically located at the front of their heads for filtering the large quantities of water they take in as their gill rakers filter out the plankton they feed on (mantas eat about 13% of their body weight each week). Mobula rays have sub-terminal mouths, located underneath the head. While mantas do have teeth, they’re generally nonfunctional – a common occurrence among filter feeders.

- Mantas are relatively long-lived – up to 40+ years.

- Mantas, like other sharks, visit oceanic “cleaning stations” where they cease all movement and open their mouths and gills wide to allow in cleaner fish like wrasses and gobies who happily consume any nutritious parasites that may be present. Mantas repay the favor by not eating the cleaner fish.

- Mantas reproduce via ovoviviparity, i.e., the young hatch from eggs inside the female’s body and the pups are nourished by yolk instead of placenta.

- Female mantas give birth to only one or two pups every two to five years, and will have a maximum of 16 pups over a lifetime. By comparison, a great white shark produces a maximum of 14 pups in just one litter. This combination of long life and infrequent reproduction increase the manta’s vulnerability.

- Manta rays were practically wiped out of the Sea of Cortez due to targeted species fishing in the 1980s and 1990s, but have been making a comeback under federal protection since 2007. It is now possible once again to see, swim and engage with the mantas in the Sea of Cortez. It’s a remarkable life experience.

champion Estrella Navarro Holm. “And it was free diving that finally put that old nightmare to rest. In competition they allow us a few minutes on the rope at the surface before the dive, and I use that time to do my deep breathing, face any fears I may have, and relax into the dive. Once the count reaches zero, the rules allow only 30 seconds to get your face in the water, so you have to be ready.” Ready to dive 70 meters (230 feet) into the black of the ocean with no oxygen, no light, no friends, just the air in your lungs and your wet suit to protect you? Fear is the only rational response. “Yet”, says Estrella, “once my face is in the water the training kicks in and my diving reflex is activated. My whole system has a physiological response to my mental state and I am completely prepared to go. The first few meters are hard because my body is heavy and buoyant with air, and I have to really work to get down. But then at about 30 meters the free fall starts. It’s as if the wet suit and my skin fall away, and the water in my body merges with the water of the ocean. Each molecule of water feels very intense. It’s like flying, but in slow motion. The free fall is the most beautiful, spiritual experience – it’s what makes people free diving junkies.” Knew there had to be a payoff.

champion Estrella Navarro Holm. “And it was free diving that finally put that old nightmare to rest. In competition they allow us a few minutes on the rope at the surface before the dive, and I use that time to do my deep breathing, face any fears I may have, and relax into the dive. Once the count reaches zero, the rules allow only 30 seconds to get your face in the water, so you have to be ready.” Ready to dive 70 meters (230 feet) into the black of the ocean with no oxygen, no light, no friends, just the air in your lungs and your wet suit to protect you? Fear is the only rational response. “Yet”, says Estrella, “once my face is in the water the training kicks in and my diving reflex is activated. My whole system has a physiological response to my mental state and I am completely prepared to go. The first few meters are hard because my body is heavy and buoyant with air, and I have to really work to get down. But then at about 30 meters the free fall starts. It’s as if the wet suit and my skin fall away, and the water in my body merges with the water of the ocean. Each molecule of water feels very intense. It’s like flying, but in slow motion. The free fall is the most beautiful, spiritual experience – it’s what makes people free diving junkies.” Knew there had to be a payoff. Mexican national free diving record 21 times, she was the first Mexican on the medal podium in a free diving world championship, and she’s the first woman in Latin America to medal in the discipline of constant weight no fins. And unlike most world champion athletes, she didn’t enter her first major competition until she was 24. This gave her the time to earn a degree in marine biology from the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur (UABCS) in La Paz, widely acknowledged as one of the best marine biology programs in the country. And she’s using that degree to pursue her other great passion in life, ocean conservation. Among other accomplishments, she is co-author of a paper titled Global Economic Value of Shark Ecotourism: Implications for Conservation, that appeared in Oryx, The International Journal of Conservation, published by Cambridge University Press. Yes, the one in England.

Mexican national free diving record 21 times, she was the first Mexican on the medal podium in a free diving world championship, and she’s the first woman in Latin America to medal in the discipline of constant weight no fins. And unlike most world champion athletes, she didn’t enter her first major competition until she was 24. This gave her the time to earn a degree in marine biology from the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur (UABCS) in La Paz, widely acknowledged as one of the best marine biology programs in the country. And she’s using that degree to pursue her other great passion in life, ocean conservation. Among other accomplishments, she is co-author of a paper titled Global Economic Value of Shark Ecotourism: Implications for Conservation, that appeared in Oryx, The International Journal of Conservation, published by Cambridge University Press. Yes, the one in England. ocean conservation where she presented the shark research in which she and her co-authors demonstrated that shark ecotourism around the world currently generates US$314 million a year and supports 10,000 jobs – a vastly higher and more sustainable number than those associated with shark landings each year. That is to say, as is generally the case when speaking of wild flora and fauna, the living, breathing resources of the world are worth more to mankind alive than dead.

ocean conservation where she presented the shark research in which she and her co-authors demonstrated that shark ecotourism around the world currently generates US$314 million a year and supports 10,000 jobs – a vastly higher and more sustainable number than those associated with shark landings each year. That is to say, as is generally the case when speaking of wild flora and fauna, the living, breathing resources of the world are worth more to mankind alive than dead. march of time. One of the greatest female free divers of all time, Natalia Molchanova, became the first woman to dive 100 meters (328 feet) at the age of 44, and continued to dominate the sport for another decade. (Her son Alexey swept the Big Blue competition in La Paz and is the reigning world champion.) So that means that for the foreseeable future, Estrella can continue to both compete in oceans around the world, and create the knowledge and ambassadors to help protect them. Saving it all for the generations to come. That’s what truly makes the champion Estrella Navarro Holm the Star of the Sea of Cortez.

march of time. One of the greatest female free divers of all time, Natalia Molchanova, became the first woman to dive 100 meters (328 feet) at the age of 44, and continued to dominate the sport for another decade. (Her son Alexey swept the Big Blue competition in La Paz and is the reigning world champion.) So that means that for the foreseeable future, Estrella can continue to both compete in oceans around the world, and create the knowledge and ambassadors to help protect them. Saving it all for the generations to come. That’s what truly makes the champion Estrella Navarro Holm the Star of the Sea of Cortez.