by Sonya Bradley | All Media, Media

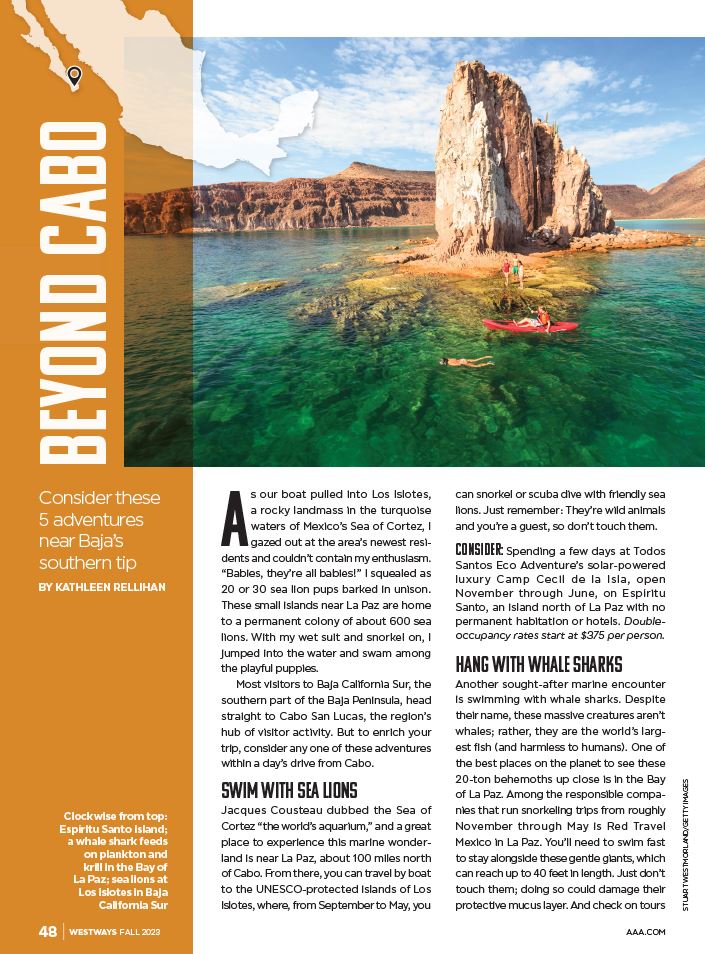

Above me, a beagle-sized sea lion pup pinwheels through the blue water of the Sea of Cortez. A second darts past with a seagull feather in its mouth, and two more nibble on the tips of the fins I’m wearing.

Scuba diving with a colony of sea lions at Isla Ilotes, a rocky outcropping at the north end of a string of islands near La Paz, Mexico, feels a little like joining recess at the local elementary school. Although my school days are long gone, I’m still having a blast.

My visit is part of a nature-focused, five-day trip to Baja California Sur, in Mexico. I’m traveling solo, and my itinerary includes a night in the artists’ enclave of Todos Santos, two nights of camping on Isla Espiritu Santo, and a night at the posh Baja Club in La Paz before I head home. But this moment, with dozens of sea lions swirling around me, tops the highlights reel.

My guide has warned me not to grab or chase the creatures, but to let them come to me. And they do.

As I swim slowly into an underwater cave where a dozen animals have gathered, a sleek brown pup with blue marbles for eyes nips lightly on the sleeve of my wetsuit. I spin around, and another tugs on the scarf wrapped over my head. I laugh underwater, and they swim into the stream of diamond-like bubbles I exhale.

The sea lions seem thrilled to have visitors.

A night in Todos Santos in Baja California Sur

Los Colibris Casitas is perched on a hillside on the outskirts of Todos Santos, in Baja California Sur. Photo by Pam LeBlanc

To get here, I caught a direct flight from Austin to the main airport in Cabo San Lucas. Then I made the hour-and-15-minute drive to the artists’ enclave of Todos Santos, where I stayed the night at Los Colibris Casitas. From the patio in front of my room at the boutique hotel, perched high on a bluff on the outskirts of town, I can see waves crashing onto the beach far below. Birds circle a fresh water estuary, and a forest of palm trees sways in the breeze. I want to get a better sense of my surroundings, so Sergio Jauregui, the owner of Los Colibris and Todos Santos Eco Adventures, volunteers to give me a tour.

Todos Santos is an artists enclave in Baja California Sur, Mexico. Pam LeBlanc photo

We drive to the town’s center, where he gives me a history lesson as we walk the streets. A mission was built here in 1723, and the last battle of the Mexican-American War was fought nearby in 1848. For the next century, farmers grew sugarcane in the area, but when the town’s main spring dried up in 1950, people moved away.

Things changed again in 1981, when that spring revived. The government paved a road into town, bringing tourists. American surfers sought it out as an alternative to California’s crowded beaches. Then artists moved in, drawn by the golden light.

Today Todos Santos supports 27 galleries, several gourmet restaurants, and a smattering of hotels. The famous song by The Eagles comes to mind when we walk past a pale orange building called Hotel California. We admire murals in the cultural center, duck into an art gallery where tiny images of dancers twirl across colorful canvases, walk across the plaza, and poke our heads into a historic mission.

Onward to Isla Espiritu Santo, part of Baja California Sur

Todos Santos Eco Adventures leads guided camping trips to Espiritu Santo. Pam LeBlanc photo

The next day, I catch a ride to La Paz. The hour-long trip takes me past mountains and thickets of tall cactus, where birds somehow manage to perch without stabbing their toes.

It’s start day for the Baja 1000 car race, a 1,000-mile off-road scramble through the desert that draws souped-up dune buggies, tricked-out pickup trucks and beat up Volkswagen Bugs. I watch a few roll down the starting ramp and speed down the oceanfront boulevard, but I’m more interested in what lies beyond.

From La Paz, it takes about 45 minutes by boat to reach Isla Espiritu Santo, a popular destination for eco tourists. Along the way, we pass a noisy colony of blue-footed boobies. The birds, which show off their teal-colored feet to impress the opposite sex, look almost cartoonish. Frigate birds, with long forked tails and hooked bills, wheel overhead. Rust-colored hills bristle with cardon cacti, their long prickly arms extended skyward, and layer-cake cliffs jut into the sea.

The boat pulls ashore in a cove, and we hoist our duffel bags onto the beach, where a crew has already set up tents. A bucket of water and a rug the size of a picnic table are arranged in front of each one, so we can rinse our feet before stepping inside. This is glamping, after all, and instead of a sleeping bag on the ground, we’ll be snoozing on real mattresses with sheets and pillows.

Camp Cecil

Guests dip their toes in the surf at Camp Cecil on Isla Espiritu Santo. Photo by Pam LeBlanc

Our guide, Andrea Hinojos, gives us a tour of Camp Cecil, another arm of Todos Santos Eco Adventures. At the far end of the cove stands a portable bathroom. There’s a solar shower, too, and, at the other end of the beach, a seating area complete with a cushy sofa. While the kitchen staff works on lunch, Hinojos briefs us on camp life.

We can use the kayaks or swim when we want, but hiking isn’t allowed past the dunes. But the ocean is the focus, anyway.

The sun rises over Camp Cecil on Espiritu Santo. Pam LeBlanc photo

That first night, just three other guests shared the camp with me ––- Joe Oliver and Christine McEnery of Carmel Valley, California, and their friend Rob Goldman of Philadelphia. We hit it off immediately, sitting on beach chairs with our toes dangling in the surf and admiring our surroundings.

McEnery tells me she was looking for a natural experience when she decided to come to the camp.

“I wanted unspoiled nature and it’s not so easy to find that,” McEnery says. She loves outdoor adventure, just like me. “It’s the visuals – looking at the desert in one direction and thinking you’re in the (American) Southwest, and in the other direction it looks like the Caribbean.”

Her husband agrees. “It’s such a departure from work-a-day life of staring at a computer screen,” Oliver says. “It’s such a treat to see great views and have them untouched by developers.”

Diving into the Sea of Cortez

Kayakers glide along a cove on Espiritu Santo, near La Paz, Mexico. Pam LeBlanc photo

The ocean around the island is part of a marine park, and we spend a lot of time exploring it. We snorkel among pufferfish and angelfish. Sea turtles the size of car tires glide beneath us. I dive down to get a closer look at a starfish.

One evening, we push off in kayaks, and paddle past mangroves flush with chirping birds. I can’t take my eyes off a pair of pelicans sitting on a rocky island as the sun sets behind them.

“It’s very beautiful,” Hinojos says, then references ocean explorer Jacques Cousteau, who spent time in the area. “It’s secluded. There are no people living here so it’s like a virgin island in the ‘Aquarium of the World.’”

And the food is far from what I’d eat on a regular camping trip. Instead of freeze-dried meals or hotdogs, chefs bring out trays of grilled fish, nachos, ceviche, and flank steak. For breakfast we have huevos rancheros and fresh fruit, and every evening we sample a new cocktail and snacks.

A night in La Paz

I love ocean swimming so much that the guides arrange one last outing before I head back to the mainland.

I leave my snorkel in the boat and dive down deep, touching the white sand on the bottom. It’s here, with the turtles and angelfish, that I feel most at home.

But finally, my water taxi arrives. I towel off and let the wind dry my hair as we speed back to civilization. In La Paz, I check into the Baja Club, then take some time to stroll along the beachfront. That night, I climb the stairs to the rooftop bar, where I sip a margarita and stare at the islands in the distance.

I’m officially spoiled.

by Sonya Bradley | Active Adventures, Adventure, Arts & Culture, Blog, Conservation, Culture, Education, History, Ranchero Culture, Travel Industry

Sustainable Ranching and the Cowboy Museum in El Triunfo

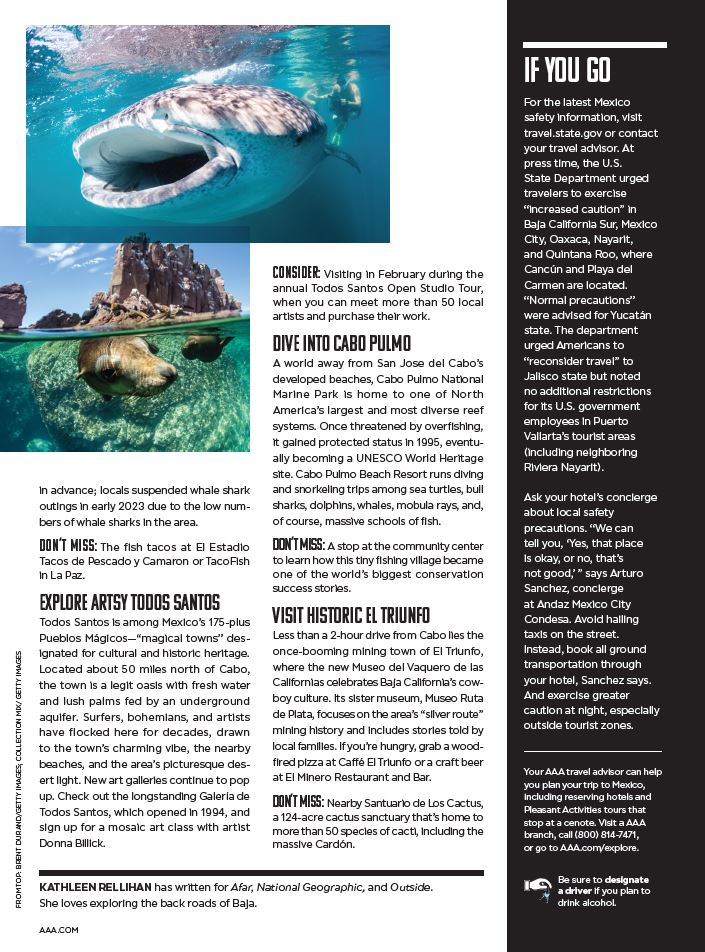

The new Museo de Vaqueros del las Californias in El Triunfo – The Cowboy Museum – is an intimate, yet gorgeously expansive look at the 300 years of families, traditions, skills and tools that bind the Californias of Mexico and the United States in ways that no war or border can erase. It is a celebration of the great vaquero / cowboy culture that was born in Baja California, moved north with the cattle to Alta California, and still thrives today throughout the western United States.

The new Museo de Vaqueros del las Californias in El Triunfo – The Cowboy Museum – is an intimate, yet gorgeously expansive look at the 300 years of families, traditions, skills and tools that bind the Californias of Mexico and the United States in ways that no war or border can erase. It is a celebration of the great vaquero / cowboy culture that was born in Baja California, moved north with the cattle to Alta California, and still thrives today throughout the western United States.

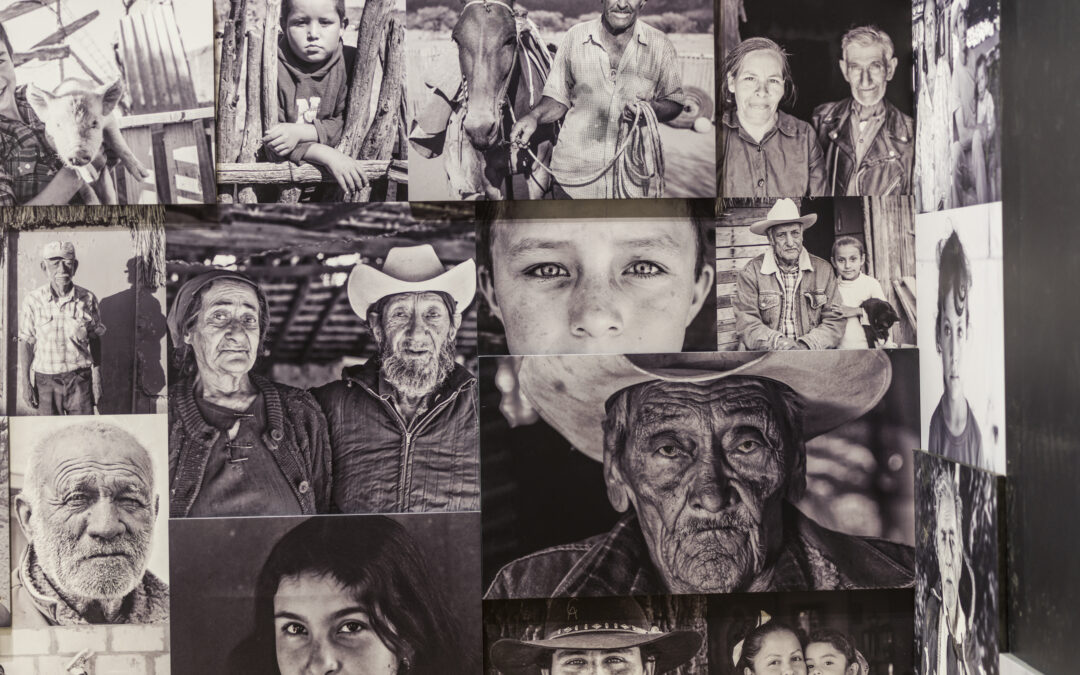

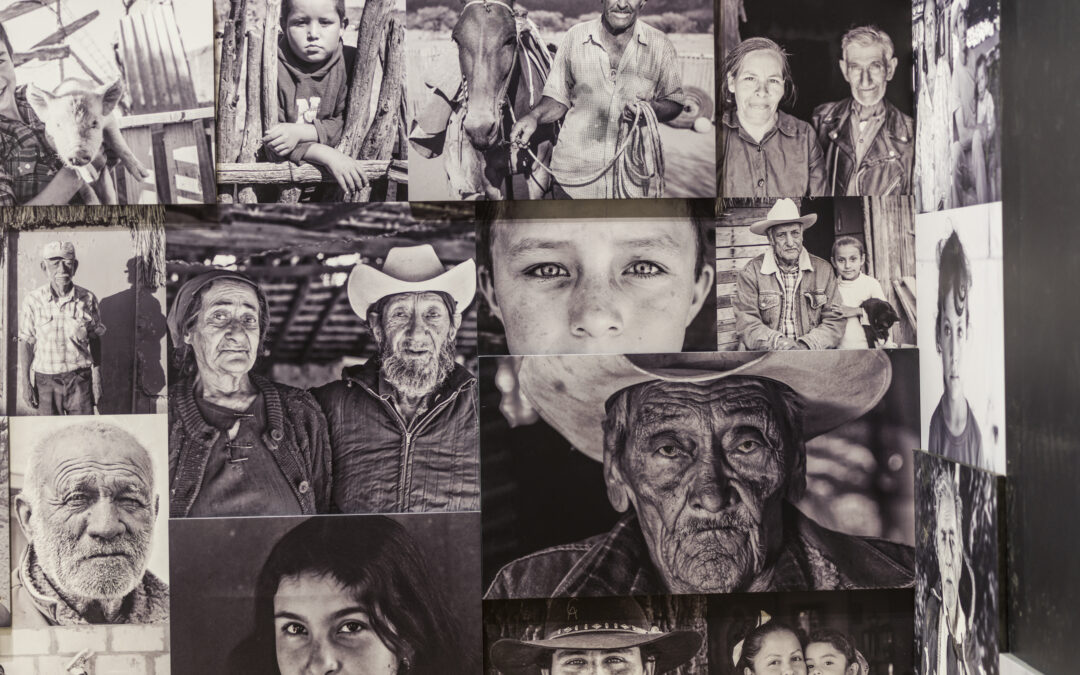

The museum exhibits are punctuated with the fantastically beautiful paintings of La Paz artist Carlos César Diaz Castro, who created ten paintings and two murals to help tell the vaquero’s story, as well as stunning photos of present-day vaquero life by renowned Baja California Sur photographer Miguel Angel de la Cueva. As with its sister museum in El Triunfo, Museo Ruta de la Plata / the Silver Route Museum, one of the museum’s most compelling exhibits is the oral history section, in which members of local ranching families share their stories, histories and anecdotes.

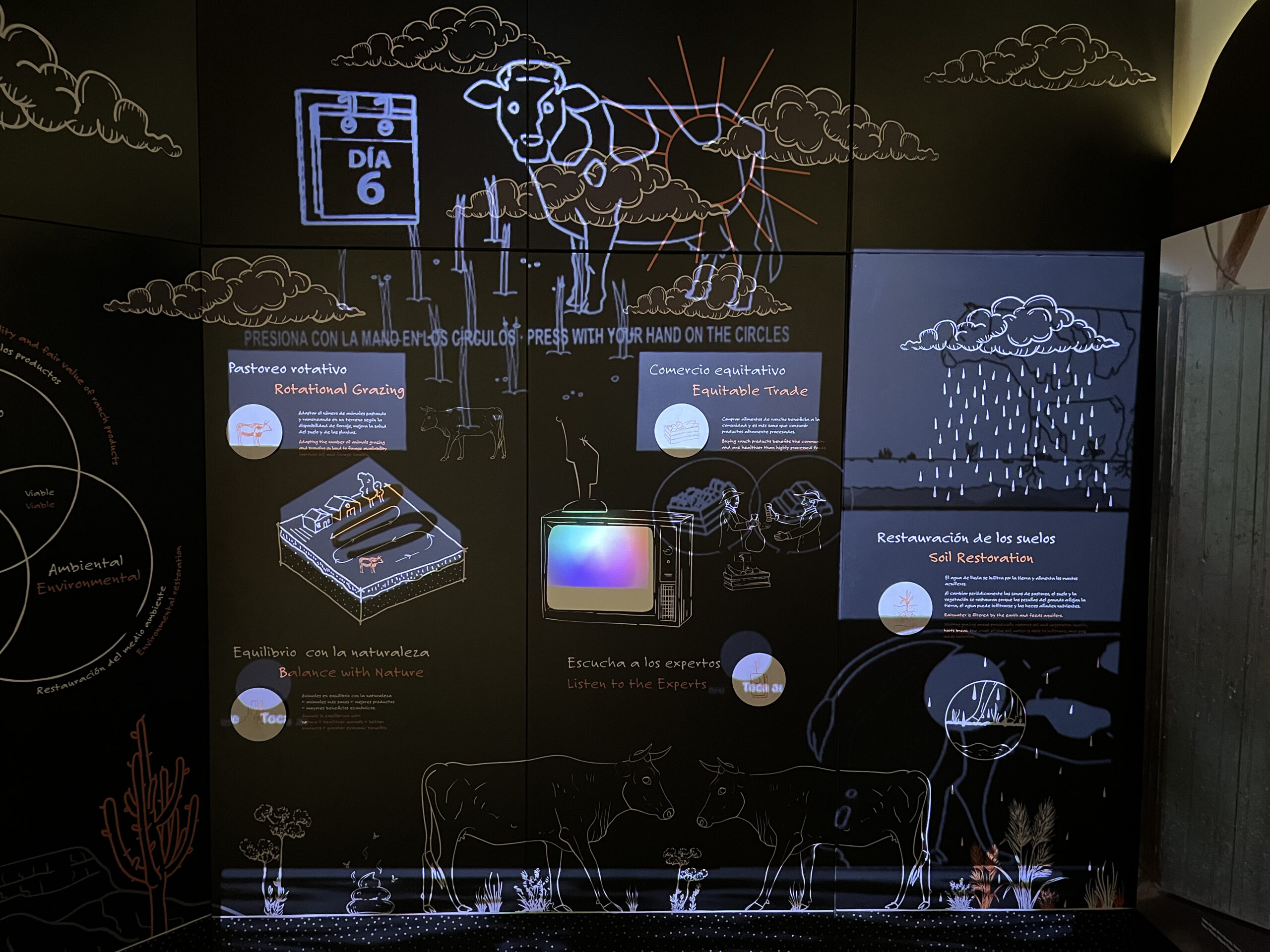

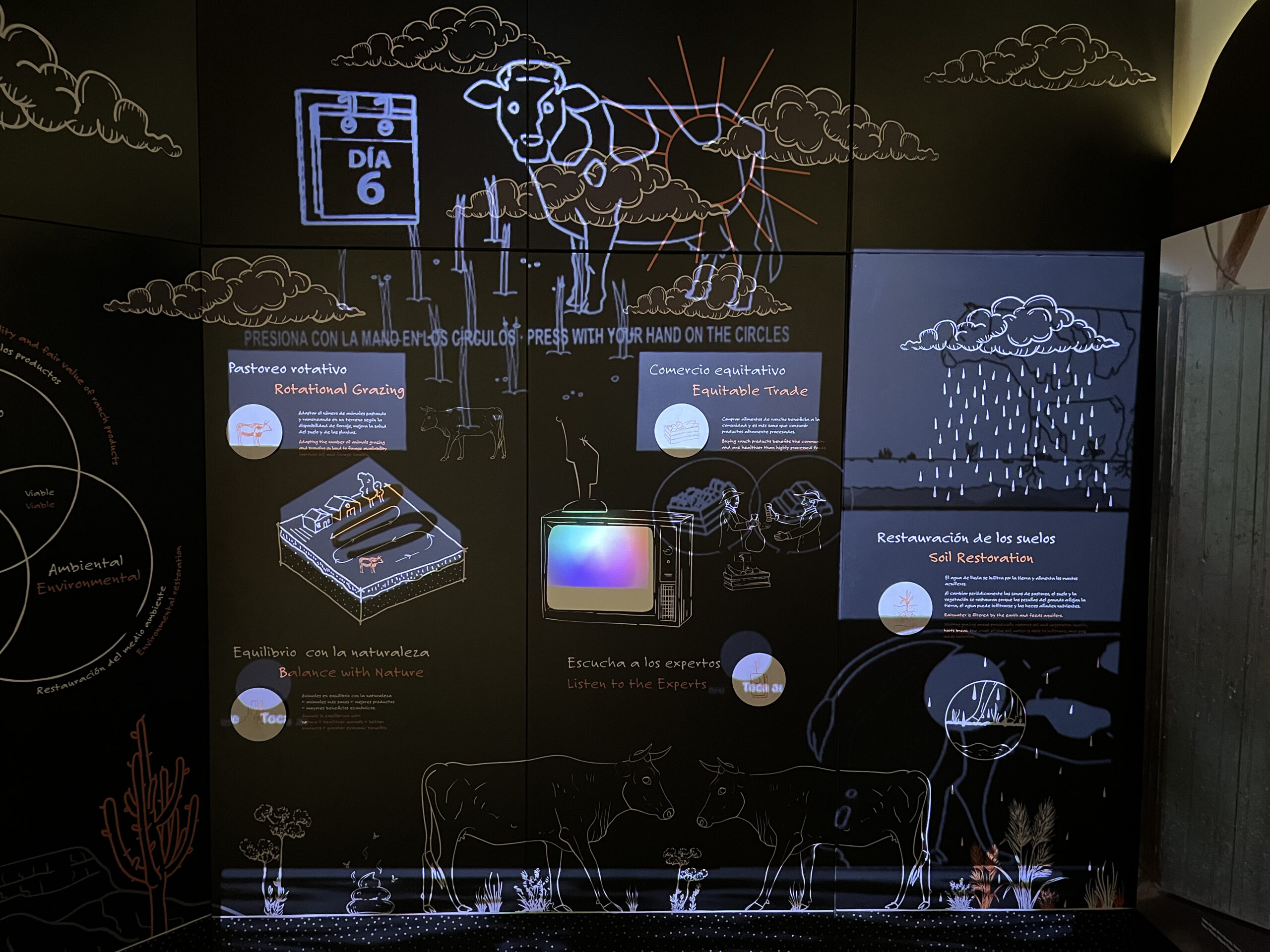

But perhaps one of the most interesting themes running throughout the museum in small plaques and chalk drawing prints is that of sustainability. Interwoven with exhibits of criollo pigs and cattle brought from the Iberian Peninsula, is the explanation of Transhumance, livestock practices with minimal environmental impact that the Spanish brought with them to the New World that involved the environmentally sustainable practice of seasonal livestock migration. This practice is now a cornerstone of regenerative cattle ranching, and you don’t have to go far from the museum to see it in action. Christy Walton’s innovacionesAlumbra, an alliance of sustainable businesses in Baja California Sur, is the owner not only of the Cowboy Museum, but also of Rancho Cacachilas – about an hour’s drive from the Cowboy Museum – where modern day cowboys are fast at work restoring the land.

But perhaps one of the most interesting themes running throughout the museum in small plaques and chalk drawing prints is that of sustainability. Interwoven with exhibits of criollo pigs and cattle brought from the Iberian Peninsula, is the explanation of Transhumance, livestock practices with minimal environmental impact that the Spanish brought with them to the New World that involved the environmentally sustainable practice of seasonal livestock migration. This practice is now a cornerstone of regenerative cattle ranching, and you don’t have to go far from the museum to see it in action. Christy Walton’s innovacionesAlumbra, an alliance of sustainable businesses in Baja California Sur, is the owner not only of the Cowboy Museum, but also of Rancho Cacachilas – about an hour’s drive from the Cowboy Museum – where modern day cowboys are fast at work restoring the land.

Florent Gomis, a Frenchman who came to Baja to study the Ecology of Desert Climates, is the Director of Sustainability at Rancho Cacachilas, and Transhumance is at the heart of his efforts. “In Baja California Sur as elsewhere in the ranching world, livestock has been blamed for the destruction of the land. In reality, the cattle aren’t the problem, it’s the management of the cattle.” Florent explains further. “Before there were vaqueros, herds of herbivores were motivated by predators to keep moving from place to place and that movement kept the land from being overgrazed. What we are working to achieve here at Rancho Cacachilas is the restoration of the impact that wild herds of herbivores once had on the land. These wild herds would continually move location, giving lands time to recover from their impact before their return. Here at Rancho Cacachilas we manage animals in groups and keep them moving, letting the land they had previously occupied rest for at least a year.”

While cattle are typically decried as destructive, Florent sees them as part of a restorative, creative process. “We really view the cattle as gardeners. When they move to a new grazing area, their hooves break the hard-packed dirt, allowing water and minerals to infiltrate the land. The cattle’s dung and urine are full soil-revitalizing carbon and nutrients, and as the cattle graze they trample these riches into the ground, resulting in the regeneration of the land. In a relatively short period of time we have seen these eroded, barren lands become covered in vegetation.”

While cattle are typically decried as destructive, Florent sees them as part of a restorative, creative process. “We really view the cattle as gardeners. When they move to a new grazing area, their hooves break the hard-packed dirt, allowing water and minerals to infiltrate the land. The cattle’s dung and urine are full soil-revitalizing carbon and nutrients, and as the cattle graze they trample these riches into the ground, resulting in the regeneration of the land. In a relatively short period of time we have seen these eroded, barren lands become covered in vegetation.”

The benefits of Transhumance don’t stop there. “One of the really cool things about this process of regenerating the soil is that it also regenerates the rain cycle” explains Florent. “Lots of vegetation on the land has a cooling effect on the atmosphere, causing clouds to precipitate on the land. So from what was once this vast cycle of death – overgrazing, monoculture, fertilizers and pesticides – you get this great cycle of life. The cows create nutritious soil so chemicals are not needed, the soil retains water and supports vegetation, the vegetation improves the soil, attracts more rain and feeds the cows, and the rain replenishes the whole, holistic system.” Florent notes that at Rancho Cacachilas, the same amount of land that could previously support only one cow, will soon support four. Moreover, with the increased vegetation for the cattle to eat, the ranch’s need for nutritional supplements for the cattle has dropped dramatically, resulting in substantial savings.

Rancho Cacachilas aims to be its own kind of Cowboy Museum. They’ve taken the lessons from the past, applied them to the present, and plan to share what they’re learning about managing cattle in the specific conditions of Baja California Sur with ranchers throughout the peninsula. The past comes alive at the beautiful new Cowboy Museum in El Triunfo. The past is alive down the road at Rancho Cacachilas.

Rancho Cacachilas aims to be its own kind of Cowboy Museum. They’ve taken the lessons from the past, applied them to the present, and plan to share what they’re learning about managing cattle in the specific conditions of Baja California Sur with ranchers throughout the peninsula. The past comes alive at the beautiful new Cowboy Museum in El Triunfo. The past is alive down the road at Rancho Cacachilas.

by Sonya Bradley | Active Adventures, Adventure, Arts & Culture, Blog, Conservation, Culture, Education, History, Ranchero Culture, Travel Industry

Pesca Con Futuro / Fishing with a Future

When Christian Liñan decided to open his third restaurant in La Paz in 2017, he resolved to work only with 100% traceable, sustainably-caught local seafood. That made his seafood supply chain logistics pretty simple: he bought totoaba from Earth Ocean Farms in La Paz and oysters from Sol Azul in San Ignacio. That was it. “I have at least 15 different recipes for totoaba” he notes.

When Christian Liñan decided to open his third restaurant in La Paz in 2017, he resolved to work only with 100% traceable, sustainably-caught local seafood. That made his seafood supply chain logistics pretty simple: he bought totoaba from Earth Ocean Farms in La Paz and oysters from Sol Azul in San Ignacio. That was it. “I have at least 15 different recipes for totoaba” he notes.

A combination of the pandemic and interminable neighborhood renovation forced the closure of that restaurant, but Christian’s commitment to traceable, sustainably-caught seafood has spanned decades and was not snuffed by a mere change of circumstance. His talent was recognized by COMEPESCA, the Mexican Council for the Promotion of Fisheries and Aquaculture Products, and as of January 2023 Christian is the Baja representative of COMEPESCA’s wildly successful program Pesca Con Futuro / Fishing with a Future. Explains Christian, “Pesca Con Futuro started in the Yucatan peninsula in 2017 and became a highly successful, high profile coalition of chefs, fishermen, producers, marketers and distributors, all committed to responsible, sustainable, in-season consumption. They all agreed to abide by the rules that promote biodiversity of species in Mexico and avoid overexploitation, thereby guaranteeing the future of fishing and aquaculture in Mexico. The 120 eminent Mexican chefs in the Yucatan peninsula who committed to Pesca Con Futuro have had such a huge impact as they are able to transmit the concept of responsible consumption and sustainable fishing and aquaculture directly to consumers via their menus and cuisine. It is truly impressive to see what they have achieved.”

COMEPESCA didn’t tap Christian to be the Baja representative of Pesca Con Futuro just because he’s a chef with an interest in sustainability. Nor did they choose him just because of his degree in Marine Sciences from CIBNOR in La Paz. One of the key reasons they chose him is because he has witnessed firsthand the importance of engaging the full chain of players in protecting marine species. In 2009, fresh out of CIBNOR, Christian joined Noroeste Sustentable (NOS) in the upper Gulf of California (Sea of Cortez). At that time the fisheries of the upper Gulf had thousands of pangas, each of which was catching roughly three tons of fish daily, mainly with gillnets. There was no management system or operating agreement among the fisheries or with the distributors, with the result that all those thousands of tons of fish were just being dumped on the market and collapsing prices. Fishers were taking home only 6 to 10 pesos per kilo of fish and fish stocks were being rapidly depleted. It is therefore not surprising that some fishers were tempted to traffic in the highly lucrative totoaba swim bladder trade. The totoaba is an iconic, endemic marine fish species of the upper Gulf. Its swim bladder is highly prized in some parts of Asia for both its purported medicinal properties and as a status symbol. As totoaba swim bladders can sell for as much as USD 80,000 per kilo, they became known as the “cocaine of the sea” and attracted the same cartels in Mexico and China that traffic in such illicit substances.

Violence came to the upper Gulf, and to say that it was a complex and dangerous work environment is a severe understatement. And humans were not the only mammals that suffered from the totoaba swim bladder trade. The totoaba shares its habitat with the Vaquita porpoise, the smallest dolphin in the world. The illegal gillnets used to trap the totoaba caught and killed huge numbers of Vaquita, which rapidly became critically endangered.

It was in this environment that Christian and NOS started the Fish Less and Gain More campaign. Through incredibly hard work in the communities they were able to create an agreement among the fisheries to catch and sell fewer tons of fish, with the result that prices rose from 6-10 pesos per kilo to 20 pesos per kilo. To protect the Vaquita, they also enforced the ban on gillnets, as well as the ban on fishing in the Vaquita’s habitat. It was all going extremely well, until it wasn’t. “Unfortunately there was really no way to enforce the agreement across all the fishing communities of the upper Gulf, with the result that some areas simply ignored the agreement and ultimately after two years prices collapsed again. Gillnetting in the Vaquita habitat resumed. The NGO and donors that had supported the program decided to close it. I was so sad and frustrated.”

Which is exactly why the Pesca Con Futuro program excites him so much – all the key players in the seafood supply chain are engaged, not just the fishermen. With chefs on the front line creating demand among consumers for eco-friendly caught, traceable seafood, the fishers, distributors and marketers realize that they have to get in line with market expectations. But, notes Christian, “It is almost impossible for fisheries to get sustainable certification.” That is why Pesca Con Futuro is a champion of the Fishery Improvement Project, FIP. “The FIP is a group of organizations and people who work collaboratively to achieve the sustainability of a fishery in the shortest possible time” notes Christian. “It is a clear and simple way to share good practices and teach about traceability. Organizations that participate in credible FIPs are considered reliable sources of supply and allies of sustainable products.” The list of FIP projects in Mexico can be found at: https://fisheryprogress.org/

Christian continues, “Sustainability is the responsibility of each of us who make up the consumption, production and supply chain, a task that must be permanent. At Pesca Con Futuro we link the different actors in the value chain, making various support tools available to them to achieve informed and responsible purchases of sustainable seafood.”

Christian believes that sustainability’s time has come for the seafood market. “In the 1990s consumers were all demanding “light” products. In the 2000s it was organic produce, and now in the 2020s the public is really turning its focus to sustainability. Pesca Con Futuro is here to both increase that awareness, and to make sure that in Mexico in general and Baja California in particular that sustainable seafood practices are widespread and sustainably-caught, 100% traceable seafood is widely available to the public.”

What about that totoaba he was cooking with at his restaurant in 2017? It represents the future he hopes to see for all of Baja. Pablo Konietzko, vice president of COMEPESCA and the founder of Earth Ocean Farms, a state-of-the-art facility in La Paz which raises the totoaba explains. “In 2012 we got special permits from SEMARNAT, the agency in charge of protecting marine species, to fish for totoaba breeding stock in the upper Gulf of California. Since we brought in those first fish we have kept meticulous records such that we can fully trace the bloodline of every fish from the hatchery to the table. It is impossible for someone to imitate our fish or pass off wild totoaba as EOF-raised.” Not only is Pablo raising totoaba for the seafood market, he is helping the totoaba to recover in the wild. Notes Pablo, “For the past 7 years we have held totoaba restocking events in Bahia Concepcion in the Gulf of California, near Mulege. We have successfully released over 175,000 juveniles into the sea, and we will continue the program each year.”

Christian could not be more thrilled to be working with Pesca Con Futuro in Baja. “It is truly an honor and a privilege to do this” he says. But the work falls to each of us. Next time you order seafood at a restaurant, ask if it was sustainably caught, and if it can be traced. Only in this way can you be sure that your favorite seafood will continue to be on the menu not only for you, but for the generations to come.

The new Museo de Vaqueros del las Californias in El Triunfo – The Cowboy Museum – is an intimate, yet gorgeously expansive look at the 300 years of families, traditions, skills and tools that bind the Californias of Mexico and the United States in ways that no war or border can erase. It is a celebration of the great vaquero / cowboy culture that was born in Baja California, moved north with the cattle to Alta California, and still thrives today throughout the western United States.

The new Museo de Vaqueros del las Californias in El Triunfo – The Cowboy Museum – is an intimate, yet gorgeously expansive look at the 300 years of families, traditions, skills and tools that bind the Californias of Mexico and the United States in ways that no war or border can erase. It is a celebration of the great vaquero / cowboy culture that was born in Baja California, moved north with the cattle to Alta California, and still thrives today throughout the western United States. But perhaps one of the most interesting themes running throughout the museum in small plaques and chalk drawing prints is that of sustainability. Interwoven with exhibits of criollo pigs and cattle brought from the Iberian Peninsula, is the explanation of Transhumance, livestock practices with minimal environmental impact that the Spanish brought with them to the New World that involved the environmentally sustainable practice of seasonal livestock migration. This practice is now a cornerstone of regenerative cattle ranching, and you don’t have to go far from the museum to see it in action. Christy Walton’s innovacionesAlumbra, an alliance of sustainable businesses in Baja California Sur, is the owner not only of the Cowboy Museum, but also of Rancho Cacachilas – about an hour’s drive from the Cowboy Museum – where modern day cowboys are fast at work restoring the land.

But perhaps one of the most interesting themes running throughout the museum in small plaques and chalk drawing prints is that of sustainability. Interwoven with exhibits of criollo pigs and cattle brought from the Iberian Peninsula, is the explanation of Transhumance, livestock practices with minimal environmental impact that the Spanish brought with them to the New World that involved the environmentally sustainable practice of seasonal livestock migration. This practice is now a cornerstone of regenerative cattle ranching, and you don’t have to go far from the museum to see it in action. Christy Walton’s innovacionesAlumbra, an alliance of sustainable businesses in Baja California Sur, is the owner not only of the Cowboy Museum, but also of Rancho Cacachilas – about an hour’s drive from the Cowboy Museum – where modern day cowboys are fast at work restoring the land. While cattle are typically decried as destructive, Florent sees them as part of a restorative, creative process. “We really view the cattle as gardeners. When they move to a new grazing area, their hooves break the hard-packed dirt, allowing water and minerals to infiltrate the land. The cattle’s dung and urine are full soil-revitalizing carbon and nutrients, and as the cattle graze they trample these riches into the ground, resulting in the regeneration of the land. In a relatively short period of time we have seen these eroded, barren lands become covered in vegetation.”

While cattle are typically decried as destructive, Florent sees them as part of a restorative, creative process. “We really view the cattle as gardeners. When they move to a new grazing area, their hooves break the hard-packed dirt, allowing water and minerals to infiltrate the land. The cattle’s dung and urine are full soil-revitalizing carbon and nutrients, and as the cattle graze they trample these riches into the ground, resulting in the regeneration of the land. In a relatively short period of time we have seen these eroded, barren lands become covered in vegetation.” Rancho Cacachilas aims to be its own kind of Cowboy Museum. They’ve taken the lessons from the past, applied them to the present, and plan to share what they’re learning about managing cattle in the specific conditions of Baja California Sur with ranchers throughout the peninsula. The past comes alive at the beautiful new Cowboy Museum in El Triunfo. The past is alive down the road at Rancho Cacachilas.

Rancho Cacachilas aims to be its own kind of Cowboy Museum. They’ve taken the lessons from the past, applied them to the present, and plan to share what they’re learning about managing cattle in the specific conditions of Baja California Sur with ranchers throughout the peninsula. The past comes alive at the beautiful new Cowboy Museum in El Triunfo. The past is alive down the road at Rancho Cacachilas.

When Christian Liñan decided to open his third restaurant in La Paz in 2017, he resolved to work only with 100% traceable, sustainably-caught local seafood. That made his seafood supply chain logistics pretty simple: he bought totoaba from Earth Ocean Farms in La Paz and oysters from Sol Azul in San Ignacio. That was it. “I have at least 15 different recipes for totoaba” he notes.

When Christian Liñan decided to open his third restaurant in La Paz in 2017, he resolved to work only with 100% traceable, sustainably-caught local seafood. That made his seafood supply chain logistics pretty simple: he bought totoaba from Earth Ocean Farms in La Paz and oysters from Sol Azul in San Ignacio. That was it. “I have at least 15 different recipes for totoaba” he notes.