A Pirate, A Priest, A Partera: Three Powerful Characters Who Shaped the Spirit of Todos Santos

by Bryan Jauregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures. This article was originally published in Janice Kinne’s Journal del Pacifico

Baja California has always been something of a world apart, an isolated place with a culture and mindset not much tied to the passions and politics of mainland Mexico. It is therefore not so surprising to learn that even though Mexico won independence from Spain in September 1821, in February 1822 the mission villages of southern Baja were still unaware of the fact. British Lord Thomas Cochrane, hired by Chile to be an admiral of its navy, decided to break the news in his own way. In Chile ostensibly to help the newly liberated nations of the Americas squash pockets of Spanish resistance, Cochrane was really just a profiteer, a pirate, and the crews of his seven ships were comprised mainly of European mercenaries on the

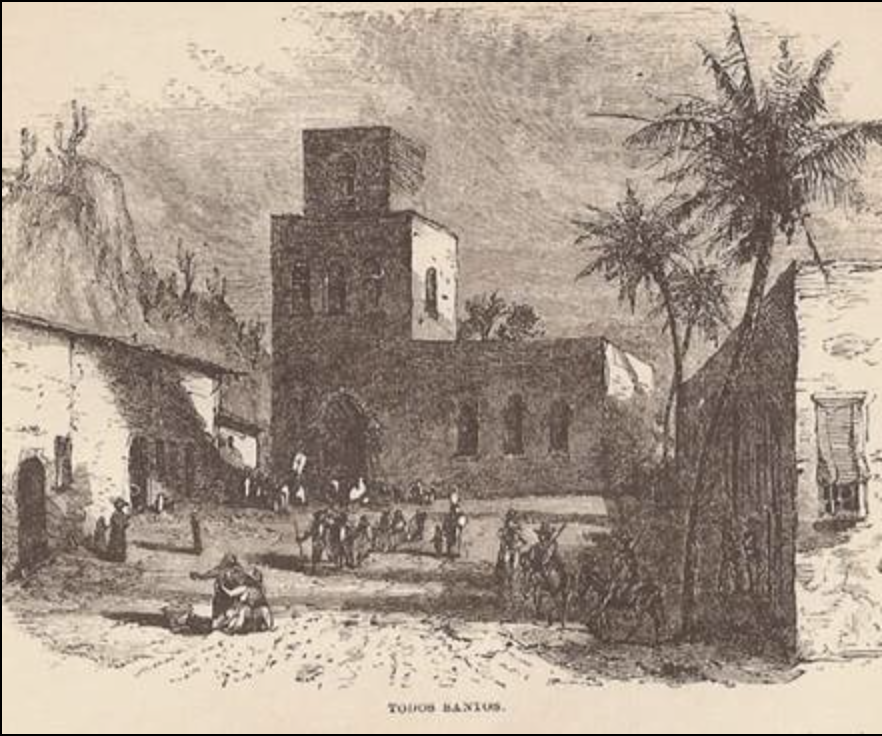

hunt for Spanish treasure. Although Mexican president de Iturbide had declined Cochrane’s offer of “help”, in February 1822 Cochrane nonetheless ordered his ship the Independenica into San Jose del Cabo where the Spanish flag was flying in the port. That flag was all the legal cover he needed to declare his pirates a liberation force tasked with removing all evidence of Spanish rule. The crew attacked San Jose del Cabo, looting everything that it could, including valuables from the mission church.

Encouraged by their success in “liberating” San Jose del Cabo, 9 pirates from the Independencia decided to head north and “free” Todos Santos. As the mercenaries sacked their mission the townspeople of Todos Santos stood calmly by. Perhaps mistaking this inaction for a general passivity of character, the pirates began groping the local women. Five of them lost their lives for this misjudgment when the men of Todos Santos demonstrated what they found worth defending in their town. Four of the pirates who didn’t die in the uprising were hauled off to prison in San Antonio. It was only when the Independencia’s captain threatened to blow up both Todos Santos and San Antonio that the Todos Santeños consented to return his crew.

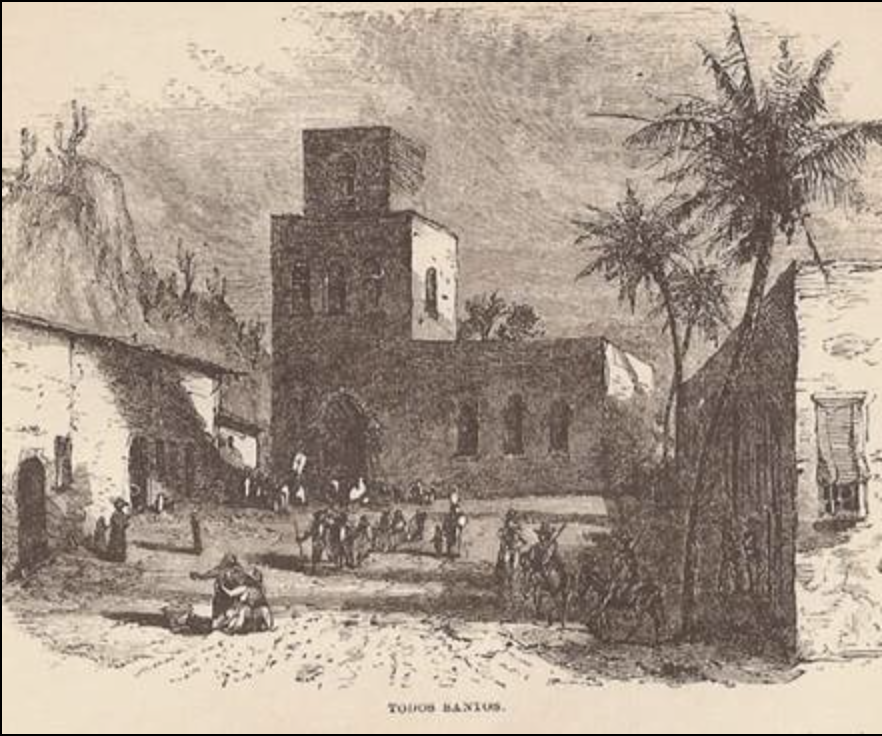

The story of Pirate Thomas Cochrane is the first in Dr. Shane Macfarlan’s wonderful introduction to the “Cultures & Characters of Todos Santos: A Pirate, A Padre, & A Partera”. A professor of anthropology at the University of Utah, Dr. Macfarlan has conducted extensive research into the culture and societies that have shaped Todos Santos over the centuries. Padre Gabriel González, a Spanish-born Dominican priest who became a caudillo, is the second of Dr. Macfarlan’s trilogy.

Caudillos were strongmen who sprang up across Latin America in the 1800s in the aftermath of independence from Spanish rule. As Dr. Macfarlan notes, “It was a time when newly-minted nations were unstable and governmental institutions were weak, a situation ripe for the emergence of charismatic leaders with political ambitions and military acumen. The caudillos provided wealth and security to their followers, demanding loyalty in return.” Priests were not usually among their ranks but then, Padre Gabriel González was not your usual priest.

“Cool, cunning and intelligent” was how U.S. lieutenant Henry Halleck summarized Padre Gabriel, adding that he was also “destitute alike of principal and honor.” The dominant figure in Baja California from his arrival in 1825 to 1850, Padre Gabriel had at least one family with multiple children, probably two, and lived with them at Rancho San Jacinto, a large holding south of Todos Santos that ostensibly belonged to the mission. There he amassed huge wealth producing tobacco, rum, sugar, corn, cattle, horses and mules. When the Mexican congress voted to secularize mission lands in Baja California, Padre Gabriel successfully negotiated to ensure that Dominican lands in Todos Santos and San Jose del Cabo remained in the hands of the church, unlike those of the Franciscans in Alta California who were forced to relinquish all of their lands and assets.

But the Mexican government kept up the pressure and in 1833 declared that all church lands had to be secularized. This time the governor of Baja California, José María Mata, set out to personally enforce the law, a fact which lead Padre Gabriel to instigate an uprising against him in La Paz. In a sign of how powerful Padre Gabriel and his forces had become, Governor Mata was captured and expelled from the peninsula. But Mata rallied and in 1837 returned to Baja, overthrew the new government in La Paz, and had his enemies arrested and sent to Mazatlán, Padre Gabriel among them. Padre Gabriel used this time to go to Mexico City and shore up political capital at the highest levels. He ingratiated himself so successfully with President Santa Ana that his mission lands were restored and he was able to return safely to Todos Santos. Mata was “retired” from the Peninsula by Mexico City in 1840, the same year that Padre Gabriel was made president of the Dominican missions throughout Baja California. The padre’s power was growing.

This cycle repeated itself in 1842 when Mexico appointed Luis de Castillo Negrete as Jefe Politico in Baja California, again with the mandate to secularize mission lands. Again Padre Gabriel took decisive action, threatening to excommunicate the governor and raising an armed force against him in Todos Santos. Soldiers in the garrison at La Paz loyal to the padre kidnapped Castillo Negrete and his brother, but the two men managed to escape and make their way to Todos Santos where a pitched battle between the padre’s rebels and the government’s forces ensued. The padre’s forces lost, so he was once again arrested and sent to Mazatlán. Padre Gabriel must have once again employed his powerful negotiating skills as once again Santa Ana pardoned him and once again his enemy was “retired” from the Baja peninsula. Padre Gabriel was now the richest man in Baja California and his hold over the evangelical, secular, commercial and military affairs of Todos Santos and the surrounding areas seemed replete. In short, he was in a perfect position to engage in espionage and guerilla warfare against US troops occupying La Paz and San Jose del Cabo during the Mexican-American war of 1846-1848.

Most accounts by members of the American forces in Baja California reference Padre Gabriel. According to Peter Gerhard writing in the Pacific Historical Review, Captain Dupont of the US Navy called Padre Gabriel the “master spirit” of the insurgents. Lieutenant Henry Halleck had a more earthy assessment. “He was living at this time in La Paz for the purposes of medical advice for the numerous diseases contracted in some of his scenes of debauchery…He manifested the most friendly feelings towards the officers of the American garrison although….he was engaged in procuring arms for the insurgents.” Indeed, Padre Gabriel would often invite American officers to his home in La Paz, serve them wine and while away pleasant hours with them playing cards. Mexican historian Pablo L. Martinez later justified Halleck’s suspicions that the padre used his parties with the Americans to gain intelligence stating that Padre Gabriel “at this time was one of the two political and military commanders of Baja California and had two sons serving as officers in the Mexican forces.” (Peter Gerhard, Pacific Historical Review) But this episode in Padre Gabriel’s life ended much like the previous two: a fierce battle in Todos Santos, the capture and arrest of Padre Gabriel and other guerrilla leaders, and the Padre’s exile to Mazatlán.

But this exile did not last long. The US-Mexico peace treaty returned Baja California to México and Padre Gabriel was allowed to return to Todos Santos in 1849. In 1851 secularization of the mission lands was finally achieved, although by this time Padre Gabriel’s family had clear title to the ranch in San Jacinto so secularization was only a professional, not personal blow to the padre. But the Dominican governance was changing and in 1855 Padre Gabriel, who had arrived from Spain 30 years before, left Baja for mainland Mexico while a titular bishop was installed in his stead. But apparently he received permission to return to Baja as an ordinary curate as the burial register of Todos Santos notes that he died there on June 1, 1868. He is reputed to have fathered 22 children, and their descendants may still visit Padre Gabriel at the family mausoleum in the Todos Santos cemetery today.

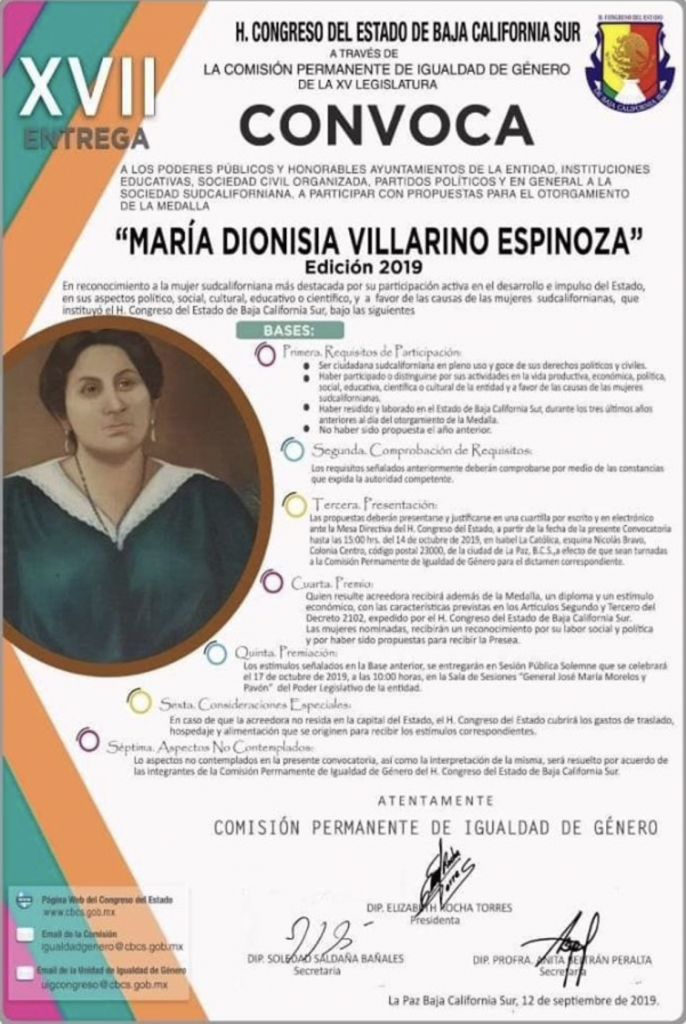

Padre Gabriel’s rebel spirit lives on in at least some of his descendents, one of whom was Dionsia Villarino Espinoza, popularly known as La Corónela. A granddaughter of Padre Gabriel, La Corónela was born in Todos Santos in 1865, and had a remarkable career that included spying for Pancho Villa’s troops during the Mexican Revolution, caring for political dissidents when she was imprisoned for her efforts, and in 1932 becoming the first woman in Baja California to legally drive a car. While her career took her to other parts of the Baja peninsula, she ended her days as a licensed partera, or midwife, in Todos Santos, where she died in 1957 at the age of 92. In 2005 the government of BCS issued a medallion in her honor, acknowledging her outstanding contributions to the state.

Dr. Macfarlan wants the current residents of Todos Santos who have historical roots in the town to be able to connect with their ancestors. Using the birth, death and baptismal records from The Guia Familiar de Baja California 1700-1900, Dr. Macfarlan has created a database of Todos Santeños and he is happy to give a copy to anyone who requests it. Moreover, he would love for families to share with him any information they have about individuals in the database to expand the knowledge available to everyone. You can reach out to him at .

“Then 25 to 12 million years ago (Miocene period), the Farallon Plate in the Pacific Ocean started subducting east at a much steeper angle again, like a curtain whipping downwards” says Scott. “This steepening angle created more volcanoes, but their location shifted back to the west, tracking with the ever-steepening, subducting Farallon plate. The volcanic rocks from this period make up a lot of the flat top mesas that you see in Baja California today in areas like Cataviña and La Purisima, as well as the massive piles of volcanic rock in the high peaks of Sierra Madre Occidental in Sonora, Sinaloa and Nayarit. The Tres Virgenes Volcanoes, in the midsection of the Baja peninsula, were formed at the end of this period. Isla Espiritu Santo, off the coast of La Paz in the Gulf of California, gets its striking beauty from the wonderfully layered volcanic rock, mostly tuff (rocks made of compressed volcanic ash), that has been gently tilted along normal faults. Brian Hausback, a geology professor at California State University, Sacramento, has dated some of the volcanic rocks of Isla Espiritu Santo to 16-21 million years old, making them older

“Then 25 to 12 million years ago (Miocene period), the Farallon Plate in the Pacific Ocean started subducting east at a much steeper angle again, like a curtain whipping downwards” says Scott. “This steepening angle created more volcanoes, but their location shifted back to the west, tracking with the ever-steepening, subducting Farallon plate. The volcanic rocks from this period make up a lot of the flat top mesas that you see in Baja California today in areas like Cataviña and La Purisima, as well as the massive piles of volcanic rock in the high peaks of Sierra Madre Occidental in Sonora, Sinaloa and Nayarit. The Tres Virgenes Volcanoes, in the midsection of the Baja peninsula, were formed at the end of this period. Isla Espiritu Santo, off the coast of La Paz in the Gulf of California, gets its striking beauty from the wonderfully layered volcanic rock, mostly tuff (rocks made of compressed volcanic ash), that has been gently tilted along normal faults. Brian Hausback, a geology professor at California State University, Sacramento, has dated some of the volcanic rocks of Isla Espiritu Santo to 16-21 million years old, making them older  than the formation of the Gulf of California seaway.”

than the formation of the Gulf of California seaway.”