by Bryan Jáuregui | Adventure, Conservation, Education, Live Music Todos Santos, Plants

by Bryan Jáuregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures

The National Geographic Society, as venerable an institution as ever graced the shores of the North American continent, has an image problem. Since 1888 the NGS has been supporting adventurers and explorers of every stripe across all the corners of the globe, and such is their success that it is now safe to say that we know it all. Satellites and surveyors, exploring on the ground and from the air, have neatly filled in all the spaces on the old maps where there used to exist nothing but the terrifying admonition: Here be dragons! Does this mean that the Age of Exploration is dead? Is there no more geography left around which a society can coalesce for discovery? Is the NGS, as some naysayers opine, obsolete?

Dr. Jon Rebman in the Sierras

Not a chance. A glance at the interactive NGS global explorers map, which shows thousands of explorers engaged in equally numerous projects across our well-mapped continents, definitively lays that notion to rest. A zoom from the global view of the map down to our own Baja California Sur shows just how vibrant an era of discovery we inhabit. Here you’ll find a hiker symbol in the Sierra La Laguna mountains just outside of Todos Santos, which is the avatar for NGS explorer Dr. Jon P. Rebman, director of the San Diego Natural History Museum’s Botany Department, and author of the definitive Baja California Plant Field Guide. Dr. Rebman’s work demonstrates not only that the Age of Exploration is alive and well, but that we are always gaining a deeper knowledge of the areas depicted on our maps. Perhaps more importantly, we are conserving the existing knowledge of these areas that is in danger of slipping away.

Explains Dr. Rebman. “After 20 years of floristic research on the Baja California peninsula and adjacent islands, my colleagues and I created an annotated, voucher-based checklist of the vascular plants of Baja California. We published this in 2016, and when we compared it to the only floristic manual for the entire Baja California region published by Wiggins in 1980, we found that we had added more than 1,480 plant taxa to the area, including approximately 4,400 plants (3,900 vouchered taxa plus 540 reports), of which 26% are endemic to the region. As part of this process we identified several plants in Baja California that are very rare and only known from one to very few collections.”

“We got focused on the need for conservation efforts to protect the region’s rare flora during a November 2013 expedition in the Cabo Pulmo area to document biodiversity in an area slated for development. My colleagues and I documented two plant species that had been lost, meaning not collected or scientifically documented, for decades. One of these rediscoveries was Stenotis peninsularis (Rubiaceae), a micro-endemic species that was last collected in 1902 by T.S. Brandegee. Yes, that means we had not seen this species in over 110 years!”

Inspired, Rebman continued his quest for the lost plants of Baja during a workplace re-assignment from San Diego to La Paz August 2015 to June 2016. Working with local Baja botanists, he rediscovered approximately 50 plant species in the Cape region that were known from just one, or a tiny number, of historical specimens. But there were more. Specifically, there were 15 more “lost” plants, all endemic to the Baja California peninsula, that had been collected between 1841 and 1985, but had not been seen since. Rebman was intent on finding them. “With the ever-increasing detrimental impacts to native plants and natural landscapes, I realized that the time was now to attempt to re-discover some of Baja California’s very rare, unique, and presently “lost” plants before they are gone forever.” The National Geographic Society agreed to fund the project, and Rebman got his Mexican colleagues – Dr. Jose Luis Leon de la Luz, Dr. Alfonso Medel Narvaez, Dr. Reymundo Dominguez Cadena and Dr. Jose Delgadillo – to join the effort. But how do you find a “lost” plant? It’s not for the faint of heart – spiritually, physically, or intellectually-speaking.

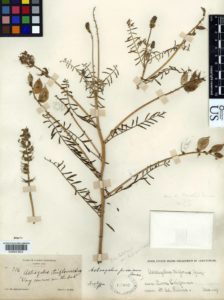

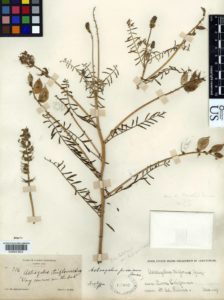

Astragalus piscinus: an image of the holotype specimen deposited in the united States national Herbarium (uS) at the Smithsonian.

Consider. In March 1889, self-taught British botanist Edward Palmer disembarked from a boat at a place on the Baja peninsula that he called “Lagoon Head”, found what he thought was a common weedy plant, and deposited it in an herbarium without further ado. Sometime later, renowned American botanist Marcus E. Jones found it in the herbarium, realized it was a very rare, endemic Baja California plant species, named it Astragalus piscinus, (common name Lagoon Milkvetch), and that was the last time anyone recorded it. In 1884 noted California naturalist Charles Orcutt was in a place he christened “Topo Canyon” when he chanced upon the very rare Physaria palmeri, took a sample, and recorded it with the fledgling San Diego Natural History Museum. No one has noted a sighting of it since. The entire list of the 15 lost plants Rebman and his colleagues set out to find reads like this, with very precise information about the plant, but incredibly imprecise information about the location. Therefore, the first thing the team had to do was pore over the papers, books and letters of the botanists who originally discovered the plants, and do their best to figure out where, exactly, in this 1,000 mile long peninsula, these botanists were when they took their samples. As a result, one of the cool byproducts of the expedition is a map put together by the NGS team that shows the place names used by these early botanists with the actual place names in use today. As every good cartographer knows, maps are an ever-evolving business.

The team narrowed down the possible locations for each plant (“Lagoon Head” turns out to be near Scammons Lagoon and “Topo Canyon” in the mountains of northern Baja), but then they had to actually find these very rare plants in an area that they had already demonstrated held over 4,400 different plants. It would seem almost impossible to make any progress while stopping to investigate all the different possibilities. Unless, of course, you are already so familiar with all the plants that you can immediately discern the one you don’t know, the one you’ve only seen as a specimen or a drawing. John Rebman and his Mexican botanical collaborators are quite possibly the only people alive today to stand a chance of finding any single one of these 15 lost plants. Yet so far, they have looked for ten and found seven. For the others, they need to wait for rain, in Baja, to find the blooms.

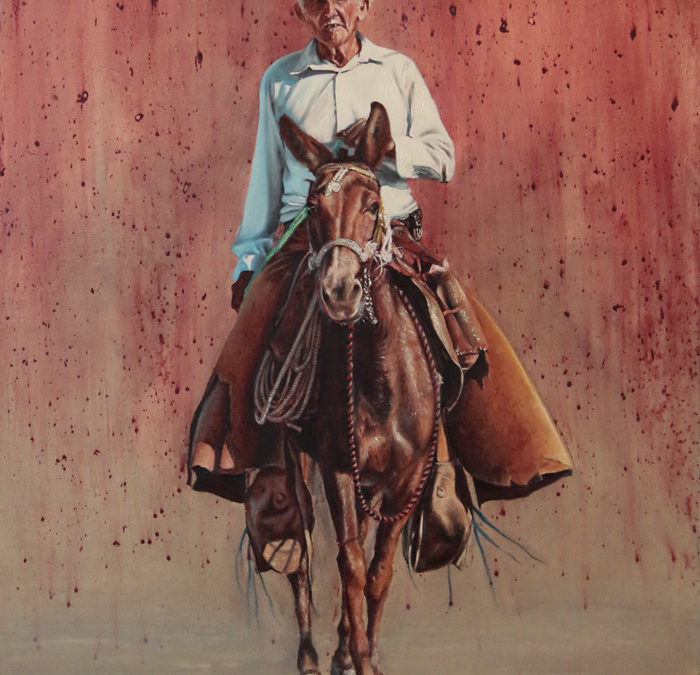

“It has not been easy” remarks Rebman. “We were in a desolate area in northern Baja where bandits are known to congregate, and I was looking for Orcutt’s

Astragalus piscinus flowers. Photo by Jon Rebman

Physaria palmeri. There were signs that the bandits were around, and alarm bells were going off in my head. But I had read Orcutt’s journals, had a firm sense of where he had been the day before he discovered the plant as well as the day after, and I really believed I was close. Yet I kept not finding the plant and kept getting more nervous. Finally, I decided that if I hadn’t found it by the time I reached the next tree, I would turn around. I got to the tree, got off my horse, looked down, and there it was. Orcutt, probably found it when he stopped to take a break in a shady spot all those years ago.”

Finding each of the 7 plants they’ve recovered so far has required serious expeditionary skills and effort, with horses, burros, camping gear, local guides, packed water and food. It’s been hot, it’s been dusty and, as we have seen, sometimes it’s been scary. But, as happens with most NGS projects, the results have been quite tidy. Says Rebman, “For each “lost” species that we encountered, we scientifically documented each population using standard protocols to make an herbarium specimen, we recorded all necessary label data, took a census of the populations, and assessed any visible threats to the well-being of the plant populations. Primary herbarium specimens have been deposited in the SD Herbarium at the San Diego Natural History Museum, and duplicate specimens have been deposited in the HCIB Herbarium in La Paz, Baja California Sur, and the BCMEX Herbarium in Ensenada, Baja California. I photographed each re-discovered plant using a digital camera, and these images, along with the map depicting old and new place names together, can be found at bajaflora.org.”

Dr. Alfonso Medel Narváez with Bouchea flabelliformis (Verbenaceae). Photo by Jon Rebman

While looking for the “lost” plants of Baja, Rebman and his team actually made several new discoveries. “From the expeditions we have taken so far, we have already encountered 30 new species previously unknown to science, all sitting in my cabinet awaiting further investigation.”

The NGS likes to quote American explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson, who said you never should have an adventure if your planning is good and you pull off every detail; an adventure is when things go wrong. With multiple expeditions looking for 15 ultra-rare – or possibly even extinct – plant species in poorly-described locations, there is bound to be an abundance of adventure in the process for Rebman and his botanical collaborators. But that is the essence of discovery, the essence of exploration, and Rebman and his team are showing us that there is still a huge amount to be discovered, and re-discovered about the places where the dragons used to roam.

by Bryan Jáuregui | Homepage, Wildlife

by Bryan Jáuregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures

This article was originally published in Janice Kinne’s Journal del Pacifico

Blue-footed Boobies at Isla La Gaviota in the Sea of Cortez. Photo by Colin Ruggiero

At a time when over half the single people in the Americas have created an online dating profile through which they send out their virtual avatars to court potential partners, it may be difficult to remember the days of Saturday Night Fever and Strictly Ballroom when plumage and dance moves were everything. But off the coast of Baja California Sur on islands like La Gaviota, Isla Isabel, and Isla San Pedro Mártir, dancing to show off mating suitability is alive and well, although the practitioners looked so silly to early outside observers that they earned themselves the name of Booby, from the Spanish word bobo meaning “stupid” or “clown”. Pretty much your worst dancing-in-public nightmare.

But the Blue-footed Boobies of Baja remain unruffled, secure in the knowledge that shaking their tail feathers has resulted in what is possibly the largest Blue-footed Booby colony in the world. And it’s not just the moves that are important in their dance, but the exact cerulean hue the footwork displays. Blue-footedness, it turns out, is enhanced by the bright yellow pigments found in the carotenoids of the fish the birds consume, so those who catch and eat more fish get bluer feet. Ipso facto bluer feet connote better health, better health connotes greater ability to provide for a nest, and as every dancer in life thinking about raising a chick knows, those are the moves that really count in a mate. So the booby dance includes a series of steps in which the feet are raised up to allow potential partners to inspect their blue-ness (apparently a vibrant aquamarine is the most desirable) and determine if that’s the blue they want to get tangled up in. And unlike in some species in which only the male sports the color, in boobies both sexes are focused on the blue tones of a potential partner’s feet. In fact, males will avoid mating with females whose blue feet have been dulled with paint. With boobies, it definitely takes two to tango.

Blue-footed Boobies. Photo by Colin Ruggiero

And in many cases, three. Researchers have found that Blue-footed Booby rookeries could easily provide source material for the most salacious telenovelas; in over 50% of booby couples one or both partners engage in what scientists call extrapair behavior (what the rest of us would call an extramarital affair), and it is not at all uncommon for a booby to toddle off for a quickie with the neighbor while its mate is out foraging at sea. Dr. Hugh Drummond, Professor of Biology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), who has studied the Blue-footed Boobies at Isla Isabel for the last 37 years, notes his education on this point. “There was a time when we thought that all bird species were monogamous and mated for life. This couldn’t be further from the truth. The majority of studies indicate extra pair behavior in birds. This is not surprising in males as this behavior can provide them with extra offspring at no cost. What is surprising is that in the vast majority of bird species, including the Blue-footed Booby, the females stray. It’s surprising because this behavior can be accompanied by some fairly high costs.”

Scientists, being scientists, have been searching for a rationale for the female booby’s lustful leanings as “because she can” doesn’t square in a world in which behaviors are generally explained by survival and advancement of the gene pool. The working hypothesis was that a female who is nest hopping with the neighbors must be doing so because she is not paired with the ideal biological partner, and is therefore driven to hook up with a better set of genes. But, as Dr. Drummond notes, “Most studies have found no difference in the success of the mated pair’s offspring versus the success of the extra pair’s offspring. The extra pair males have not consistently proven to provide better genes than those of the mates. So we have to consider that the female’s behavior may not be for the benefit of the offspring after all.” Have female boobies liberated themselves from the Darwinian grind?

Blue-footed Booby in the Sea of Cortez. Photo by Colin Ruggiero

Possibly, but the males aren’t taking it lying down. They will destroy an egg in their nest if they suspect it was fertilized by another, and if the female was out of their observation range for a few hours or more during the 5 days of fertility prior to egg laying, then they are definitely suspicious. Dr. Drummond and his colleagues tested this by “kidnapping” males during the 5 critical days. Under these circumstances, the males destroyed the first egg subsequently laid, ensuring that they didn’t have to raise some other guy’s chick. If they are kidnapped prior to the fertile period they leave the egg alone. Male boobies will actually abandon particularly perfidious partners, and seek out others to soothe their ruffled feathers. Says Dr. Drummond, “Isla Isabel has roughly 2,000 pairs of Blue-footed Boobies, and at the end of every season half of the pairs break up.”

Before egg incubation starts, nearly all male boobies on Isla Isabel court extra pair females, while roughly one third of the females develop sexual relationships with one or more male neighbors. But booby mates who retain the same partner for successive years definitely reap gene pool rewards – Dr. Drummond has found that they produce 35% more offspring those who change partners. And while all booby couples share in parental duties, longtime mates spend equal time caring for their young. They are completely in it together, with males spending just as much time as their mates on household duties. Female boobies. Has their behavioral long game all along been shaping male boobies into the perfect domestic partner? That would be a remarkable evolutionary feat!

While longtime mates may cohabit harmoniously, harmony is definitely not a word one would associate with their offspring in the nest. Dr. Dave Anderson, Professor of Biology at Wake Forest University, has studied boobies in the Galapagos Islands for most of his adult life. He explains. “Nazca boobies (the Blue-foot’s cousin) only want one chick but they sometimes have two by mistake when their extra insurance egg hatches. In such cases, 100% of the time the older (or healthier) chick will force the other one out of the nest with no parental interference, and perhaps even some parental facilitation. Once out of the nest, a chick has no way to survive on its own. Nazca boobies nest on the ground in such a way that the nest is essentially a gladiatorial arena that the parents observe from on high.”

“The Blue-footed Boobies, on the other hand, do want the option of having two chicks. So they will give the first egg a head start of 3-5 days before laying the second egg, such that a natural dominance hierarchy is established among the resulting chicks. If food is abundant, they will raise both chicks. However, the first-hatched chick fiercely beats up the second-hatched, and the second-hatched survives only by adopting submissive behavior.” Dr. Anderson points out that the parents help the subordinate by building nests that are bowl-shaped, which means that when the older chick is pecking the younger one, at least for the first ten days or so, the poor little guy generally doesn’t fall out of the nest like its hapless Nazca counterpart – there are walls to keep it hemmed in. Further, unlike the murder-permissive Nazcas, murder-restrictive Blue-footed Booby parents will actually sit on their chicks to prevent the dominant from killing the subordinate.

Dr. Anderson tested what would happen when the constraints of the parents and the bowl-shaped nest are removed. “What is really interesting,” says Dr. Anderson, “is when we put Blue-footed Booby chicks in Nazca nests with Nazca parents. They are much more aggressive than when in their own nests. And when we put Nazca chicks in Blue-footed nests with Blue-footed parents, they still want to kill each other but can’t because of the shape of the nest and the murder-restrictive Blue-footed parents.” They may fool around like mad, but the Blue-footed Boobies do draw the line at siblicide, unless of course, food is scarce – as in an El Niño year – and subordinate chick sacrifices must be made.

Blue-footed Boobies. Photo by Colin Ruggiero

Now you may well imagine that the poor second-hatch chicks, having been so horribly abused by their siblings and practically starved to boot, would turn into physically stunted adults, emotionally crippled by their circumstances and consigned to a lifetime of failure. “Not so!” says Dr. Drummond. “We compared 1,167 fledglings of two-chick broods for 10 years and found few differences between first-hatched and second-hatched birds. Even more surprisingly, where there were differences these tended to favor subordinates.” By almost every measure that counts in a booby’s biological life, Dr. Drummond found that the subordinate chicks matched or bettered those of their dominant tormenters including survival, defensive ability, brood size, nest success, and cumulative brood size over the first ten years of life. Blue-footed Boobies. Liberated females, progressive males, bullies not allowed to flourish over others. What else can we learn from our blue-footed friends?

Every mating season the Blue-footed Booby males stake out their territories and wait for females to come by and notice them. “The males then fall all over themselves trying to demonstrate their suitability as a mate” says Dr. Drummond. One would think in such circumstances that younger, more virile (and of course bluer-footed) birds, would rule the day. But once again, things are not always as one would imagine in the booby world. Dr. Drummond and his colleagues have found that May-December romances among the boobies, i.e., partnerships in which one bird is old and one bird is young, produce offspring that are significantly more likely to later become parents themselves compared to the offspring of parents of a similar age. And it doesn’t seem to matter which sex is at which end of the age spectrum, old mothers and young fathers or old fathers and young mothers, the results were the same in the 3,361 booby offspring that Dr. Drummond and his colleagues studied – breeding in age-mismatched parents provides greater success in contributions to the gene pool than those of similarly aged parents. In fact, the advantage to the chicks born of May-December parents was almost as great as those conferred on chicks whose parents are in long-term partnerships. Why this is so remains a scientific mystery. Could it simply be that Blue-footed Boobies are as socially evolved as the French?

So now we know that these dancers who looked so silly they earned themselves the name of Booby may actually have some elegant lessons to share across species: 1. A rough start in life need not define your later years; 2. Sharing equally with a long-term partner produces better health for the family; 3. Age does not necessarily define your ability to contribute to society; and 4. Dancing your heart out no matter what you look like to strangers is one of the keys to a successful life. In fact, the future of the species depends on it.

© Copyright Sergio and Bryan Jauregui, Casa Payaso S de RL de CV, 2017

by Bryan Jáuregui | Culture, Plants

by Bryan Jáuregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures

This article was originally published in Janice Kinne’s Journal del Pacifico

Only a limited number of reasons come to mind when considering why someone would willingly allow themselves to be bitten by a venomous snake. There is, of course, suicide by snake, popularized by Cleopatra who reputedly smuggled an asp (cobra) into her chambers to kill herself and her hand maidens as Egypt fell to the Romans. Closely related is spirituality by snake, in which believers handle venomous snakes as a testament to their faith. The snakes snuff out the posers. And then there is science by snake, in which investigators inject themselves with venom to build up immunity, then test that immunity with actual snake bites (see suicide by snake).

So when Catarino Rosas Espinosa, widely known as Don Cata, said that his father deliberately provoked a rattlesnake to bite him, it’s initially difficult to make sense of the story. Don Cata’s father, Hipólito Rosas, was a renowned curandero, or healer, in the Sierra La Laguna mountains of Baja California Sur (BCS). Born in 1890, Hipólito was growing up at the height of the mining frenzy in BCS, a time when many Europeans were moving to Baja and bringing more “advanced” notions of medicine and civilized society. It was a time that saw a huge influx of grand pianos into the state as a reflection of increasing wealth, and a rapid decline in the number of people experienced in the traditional healing arts. People wanted to purchase their cures over the counter.

Although he worked for the mines for a time, Hipólito did not embrace all the modernizations brought by the Europeans. In fact, the Europeanization of local culture prompted him to seek out those who had been practicing traditional medicine in Baja long before the arrival of even the first wave of Europeans almost 500 years ago – he sought out families in the Sierras who still have the blood of the now largely extinct native peoples of BCS – the Guaycura and the Pericu – running through their veins. Under their tutelage he became a great healer renowned throughout BCS, working with 81 plants in the area that have healing properties, and using them to treat everything from allergies and bug bites, to cancer and diabetes. But the most important lesson he learned, and the one he felt most critical to impart to his son Catarino, is the power of mind over matter.

Don Cata and Dona Luz

By the time he was a teenager Don Cata was already an accomplished healer himself, having worked alongside his father since he was a small child. He saw that with every single patient Hipólito would end the consultation with a pep talk, telling the patient that everything was going to be fine. Don Cata says his father was cueing his patients’ minds to help heal their bodies. When Don Cata turned 16, Hipólito decided it was time to make flesh this lesson of mind over matter, and so set the rattlesnake upon his son.

Today Don Cata is a very healthy and youthful 65 years old, but he can still remember vividly the painful, lethal venom coursing through his veins, and the intense struggle to dominate it with his mind, keeping it from reaching his heart. He says that power of positive thinking, of the mind dominating the body, is critical to good health, and one of the best ways we can help ourselves prevent and/or recover from illness and injury. But how does one get a mind that is so powerful it can stop rattlesnake venom from reaching the heart? Plants. Says Don Cata, “I like to look for plants that have very long lives, lives that are longer than ours, old plants that are full of sustainable, renewable energy. When I see a really large, obviously old tree, I hug that tree with my whole body and with lots of love, and that tree shares its energy with me. When I go up in the mountains, I prepare tea from the root of a long-lived fern that grows there, and every day I drink 3 cups of this tea just before bed. I consider problems I need to resolve or areas in which I need help, and after drinking this tea at night solutions and knowledge come to me. After 15 days in the mountains of drinking this tea every day and walking in a different altitude, I have great clarity of mind and feel like a young man when I return to my ranch.”

Omar Piña is a 39 year-old traditional Mexican medicine expert who has studied with native peoples, shamans, curanderos and rancheros throughout Mexico. Omar, who holds several certifications in holistic health, says that traditional medicine is “based on a harmonious relationship with all the elements of the earth with whom human beings coexist, but do not master. (Emphasis is the author’s.) Many diseases and natural phenomena that affect people’s health are associated with a poor relationship with the beings of nature.” Omar, whose father is an MD, notes that in Western medicine, if a process cannot be readily understood it is generally dismissed. But Omar, Don Cata and other practitioners believe that people can connect with the spirit of the plant, and that plants can both heal you and prevent disease, whether this is an explicable phenomenon or not. All these healers have their go-to plants for particular ailments and issues (see The Power of Plants in Your Baja Garden) but they all believe that how you deal with the plant has as big an impact on the results that you may get as any chemical properties inherent to the plant itself. Explains Don Cata, “You must transmit love to the plant and give thanks to the plant, as well as the land and the earth. Otherwise it will die. We never take the whole plant for a medicine, we just take what we need.” Omar agrees. “To reap the full benefits of the healing or restorative properties of the plant, you must ask the plant for help. When people have a physical symptom, they must ask for the help so that they can start looking deeper for the root of the problem in their souls.”

Omar Pina

Omar says that the rancheros of BCS like Don Cata are fully responsible for their emotional and physical well-being in ways that many of us in the west are not. “In modern times we have such large egos we think we can solve everything but we cannot. We just want to take a pill for the problem, without digging deeper into its origins. The Baja Rancheros and the native peoples of Mexico have so much respect for the earth, the things we cannot see, and for being connected to everything around us.”

Omar is living testimony to the power of plants to heal one’s soul and maintain balance in life. In 2010 Omar’s brother was kidnapped in Monterrey N.L. and has never been seen or heard from again. The shock of such an almost unimaginable event caused Omar’s mother to suffer a stroke, and plunged Omar into a profound emotional crisis. But, says Omar, “In this most difficult moment of my life, traditional medicine and plants taught me so much about life and spirituality, and brought me back to emotional health. It is this inner process of healing myself, of healing my soul, of finding balance with the help of the plants that I want to share with others.” The kidnapping of your brother – that’s a lot of venom for your mind to keep away from your heart.

Carlos Casteneda, the famed author who wrote several books about the teachings of a Mexican shaman concluded, “The aim is to balance the terror of being alive with the wonder of being alive.” Omar has succeeded in doing just that, and sharing this knowledge is now his life’s work. “Traditional medicine is sacred, it comes from god, it’s related to god” says Omar. “It is of and for the community – it belongs to everyone.” Don Cata agrees. People throughout the Sierras seek him out for healing, but he feels that his main purpose is to teach them how to use the plants themselves. “When friends visit, or when I’m working on projects on ranches with others, I always try to give them the knowledge for themselves and their families, and encourage them to pass it on to others.”

The great Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt wrote, “Nature everywhere speaks to man in a voice familiar to his soul.” Man just needs to open himself to hear that voice. Mind over matter.

© Copyright Sergio and Bryan Jauregui, Casa Payaso S de RL de CV, 2017

by Bryan Jáuregui | Adventure, Culture, Ranchero Culture

by Bryan Jáuregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures

This article was originally published in Janice Kinne’s Journal del Pacifico

The American Cowboy is the quintessential symbol of what made America great: strong character, diverse skills, creative problem solving, resilient nature and beef on the table. The iconic cowboys loved their whiskey, played their harmonicas, and sported nicknames like Cactus Pete, Deadeye Jake and Kid Curry. But If you look under the buckskin a bit you’ll find that the original American cowboys likely preferred tequila, played bass fiddles, and had nicknames like El Coyote, Güero de las Canoas and Dos Santos Biel. And that’s exactly why Meg Glaser, Artistic Director of the Western Folklife Center in Elko, Nevada invited 5 Baja California Sur vaqueros (cowboys) to be the guests of honor at the 31st National Cowboy Poetry Gathering: they are the living link between the Spanish missionary soldiers that came to Baja California 300 years ago, and the American buckaroo. Yep, as surely as the Statue of Liberty came from France, and the melody of the Star-Spangled Banner came from England, the American Cowboy came from Mexico. Juan Wayne would have been a more apt screen name for the Duke.

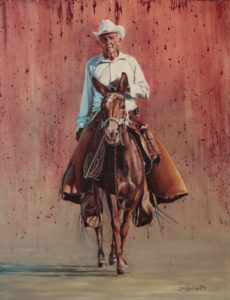

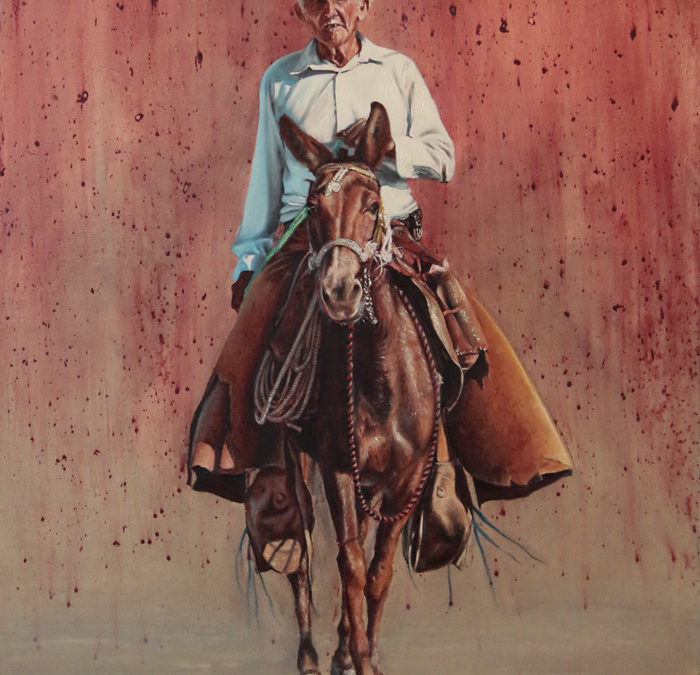

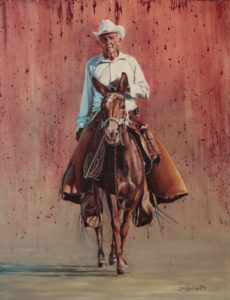

Don Jose y La Pancha. Painting by Carlos Cesar Diaz Castro

The Western Folklife Center (WFC) focuses on making connections with other horse and ranching cultures from around the world. They have hosted cowboys from the far-flung corners of the earth, including Mongolia, Hungary and Brazil, but nothing they had ever done prepared them for the challenge of hosting the vaqueros of Baja California Sur. Says Meg, “The BCS vaqueros live almost completely off the grid so they didn’t have passports, US visas, or even email access. It was incredibly challenging to get these men who live on roadless ranches, some of whom must ride 6 hours on mules to get to the nearest highway, from Baja to Nevada, but together with the great Baja team we did it and it was one of our most successful programs ever. Many of our buckaroos in Nevada and other parts of the west are pretty well versed on the history and the connection between the American cowboy and the Mexican vaquero, but very few of us realized that it was such a vibrant living culture. It was a real eye opener for all of us.”

Of course back in the day both Nevada and Baja were part of the Spanish California Provinces (Nevada in Alta or Upper California and present day BCS in Baja or Lower California) and cowboys and cattle – imported from Spain to satisfy the conquerors’ demand for beef – flowed freely throughout the region. In fact, the regions were so integrated culturally and linguistically that it wasn’t until the 1960s that people from Baja California were required to have a passport and visa to travel to the USA. The lingua franca of cowboys demonstrates the cultural link between the two Californias: “buckaroo” is the Americanization of the word “vaquero”, “chaps” comes from the Spanish word chaparreras, or leather leggings, “rodeo” comes from the Spanish word rodear, to surround, and “mustang” comes from the Spanish word mostrenco. The modern livestock industry in the USA continues to thrive on early Mexican techniques for handling cattle including branding, saddle cinching and using a hand-braided lariat – from the Spanish la reata – to rope cattle.

Chema with his guitar in the Sierras.Photo courtesy of Saddling South

But now there is most definitely a border, and crossing it was a tremendous experience for the whole team. Says vaquero Jose Maria Arce Arce, who goes by Chema, “Just imagine. I had to ride a mule for several hours out of the Sierras as part of the journey to the airport, then suddenly I was on a huge airplane and we flew over my ranch – I recognized it immediately and was amazed to see it from the air. This trip was my first time on an airplane and my first time in such a nice hotel. Imagine a horse that is accustomed to poor grazing areas then he’s put in a green pasture. That is what it felt like to me.” Trudi Angell has been Chema’s friend and business associate in the Sierra San Francisco since 2005, and she was the main organizer of the trip. The vaqueros nicknamed her “La Caponera” or “the bell-mare” of the trip: the one to follow. She sat next to Chema’s cousin, Bonifacio, or “Boni” on the first flight. “His eyes lit up like a kid as he turned around at lift-off and practically shouted “ ‘Chinga! The cars all look like ants!’ Forty minutes later when we flew over the Sierra San Francisco, Chema and Ricardo (Chema’s son who’s known as Teté) were pressed to the window pane and were practically beside themselves when they saw their ranch from the sky. It was a wonderful experience.”

Chema, Teté and Boni are Los Regionales de la Sierra, a musical group that plays traditional ranchero music from the northwest of Mexico, much of it resonant of eras long gone by. Chema plays accordion and guitar, Boni plays bajo sextoand accordion, and Tetéplays the northern ranchero bass fiddle. In Elko they performed often at schools, juvenile facilities and the Western Folklife Center itself, and were accompanied by singers Damiana and Duna Conde, daughters of the renowned Baja California Sur musician, comedian and political satirist Raul Conde. The crowds and other musicians simply couldn’t get enough of the group, and they were feted everywhere they went. Even Sourdough Slim, an acclaimed western singer who regularly plays the Lincoln Center and Carnegie Hall Folk Festival circuit invited the vaqueros to jam with him at the historic Pioneer Bar one evening. Observes Meg, “They were a smash sensation.”

Carlos’ stand up paintings of Boni, Chema and Tete. Part of the BCS exhibit.

The great reception to their musical skills wasmatched only by the tremendous enthusiasm for their skills as ranchers and craftsmen. Chema, Dario Higuera Meza and the other vaqueros met with American cowboys and shared information on ranching lifestyles, including working and breeding donkeys and horses. Says Chema of his American counterparts, “They are the same people that I am. I completely identified with them… the only difference is in the way they dance!” Dario, who is one of the few artisans left in BCS who knows how to create traditional ranch crafts using the old Baja California methods (he received an honorary degree from the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur in recognition of his unparalleled skills and contribution to BCS culture), gave daily demonstrations on horsehair rope making and leather braiding, and in particular bonded with several native American families over different methods of tanning and spinning rope. They were so enthralled with Dario they invited him to a Navajo festival. Chema’s nephew, Juan Gabriel Arce Arce – nicknamed Biel – gave daily demonstrations on leatherworking and other traditional ranch skills. Biel consistently wins the top prize at state-wide leatherworking contests.A traditionally tanned leather trunk that he made with ornately woven edges and beautiful hand tooling was purchased by a Basque ranching family from Elko for US$5,000.

Biel’s Chest

McKenzie Campbell, one of the people responsible for getting the vaqueros to Elko, is the founder of Living Roots, a non-profit which helps BCS ranch families capitalize on their skills. At the request of the WFC gift shop, she made sure that the group brought many leatherwork pieces made by Teté, Dario, Biel and other ranchers, includingpolainas (leather gators), miniature vaquero saddles, belts and teguas (riding shoes). McKenzie also brought other BCS ranchero crafts including embroidered purses and bags, as well as tepetes, rag rugs that women make with scraps of cloth. It allsold like hot cakes in the gift shop.

The vaqueros are direct descendants of soldiers imported by the Jesuit missionaries in the 1700s. Recruited as part of a deal with the king of Spain that gave the Jesuits administrative autonomy in Baja California in return for protecting the territory from pirates, these “soldiers” were in fact largely people from Moorish Spain who had the excellent ranching and agricultural skills the Jesuits needed to develop their missions. They became known as the “soldiers of leather” to distinguish them from fighting “soldiers of metal”. When the Jesuits were subsequently kicked out of Baja, the “soldiers of leather” who worked the missions were given the lands by administrative fiat and from that point on Baja ranchero culture flourished. Largely forgotten by the rest of Mexico for several

Fermin Building the Rancho Exhibit

generations and isolated by geography, the architecture, ranch tools, farm implements and cookware of BCS ranches remains to this day very similar to that developed by their Spanish forbears 300 years ago. “The BCS rancheros are a piece of the past that has survived until today” says Fermín Reygadas, a professor of Alternative Tourism at the Autonomous University of Baja California Sur who has worked with Baja Californiarancheros for over 30 years.

Fermín, who counts ranchers as some of his best friends in Baja, envisioned and happily executed the task of recreating a typical ranch dwelling with an hoja (palm-frond) roof and palo d’arco walls for the exhibit at the WFC. Working with La Paz artist Carlos César Diaz Castro in Elko a full month before the vaqueros arrived, Fermíncreated a truly astounding exhibit which everyone agrees captures the heart and soul of BCS ranchero life. Says Trudi, “The BCS exhibit was left up for 8 months and a woman from the WFC sent me a special note to say that the local folks from Elko came again and again to see the exhibit, bringing visiting friends and family. They had never seen this type of reaction to an exhibit before.”

Carlos Painting Tete. Photo by Karla Fernanda Amao

The whole project got started when Rick Knight, a professor from Colorado State University and board member of the WFC, went on a mule trip with Trudi’scompany,Saddling South, in the Sierras. Chema was their guide at the Sierra San Francisco rock art sites, and he and his family entertained the group around the campfire at night. Rick informed Meg Glaser of the incredible experience he had had and in 2012 Meg came down to see it for herself. She knew right away she had to get the vaqueros to Elko.Three years later – which included intensive months of effort by Trudi in the quest for Mexican passports and US visas for 5 people who live almost completely outside the system (letters to the US Consulate from Nevada Senator Harry Reid, the BCS State Board of Tourism, the Western Folklife Center and several others all had to be obtained) – the group was in Elko. The connections made between people and cultures moved them all. Says Chema, “The best part is that we went so far and met people we had become friends with at the caves in the Sierras.” Says Meg, “The best part is that the social connections extend far beyond Elko and many people have already gone to Baja Sur to visit the Sierras and learn more about the vaquero culture.” Says Fermín, “The best part was watching the vaqueros bond with the US ranchers discussing knots and ropes, sharing ideas and experiences. It really showed how connected we all are.”For his part, Dario, who is not one of the musicians, had so much fun that he wrote a song about the whole experience.

Elko Group Portrait Back Row, Left to Right: Karla Fernanda Amao (Carlos’s wife), Carlos Cesar Diaz Castro, Dune Conde, Fermin Reygadas Dahl, McKenzie Campbell, Chema (Jose Maria Arce Arce), Damiana Conde, Ricardo Arce Arce (Tete), Juan Gabrial Arce Arce (Biel), Bonifacio Arce Arce (Boni). Seated Front Row: Trudi Angell, Dario Higuera Meza, Teodora Montes Botham, Meg Glaser. Photo courtesy of Western Folklife Center.

Concludes Chema, “I never had a childhood because I’ve worked since I was a little boy. I now feel very proud that people know me and our life here at the ranch, both through the movie Corazon Vaquero and our trip to Elko. We represented the Baja California vaqueros to the cowboys of the US, and they really respect all the things we can do. It was a beautiful experience. But I’m still the same humble

Chema and his grandaughter Azu. Photo courtesy of Saddling South

rancher I have always been and I haven’t changed my way of life. All of my grandchildren are becoming ranchers and I’m very pleased about that.” Fermín calls the vaqueros of BCS “an oasis of common sense humans.” Maybe Chema’s grandkids will be the next generation of Cowboy Ambassadors, connecting US cowboys to their living roots in Baja California Sur. Could there be another ride for the bell-mare? Possibly. Trudi says her first thought when she woke up after the trip to Elko was, “We have to take this show on the road!”

© Copyright Sergio and Bryan Jauregui, Casa Payaso S de RL de CV, 2016

by Bryan Jáuregui | Conservation, Culture, Education, Plants, Wildlife

by Bryan Jauregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures

This article was originally published in Janice Kinne’s Journal del Pacifico

Lawyers, guns and money. For the last several hundred years these have been the tools employed throughout the Americas to resolve land use and land ownership issues, and the system continues to thrive in present-day Baja California Sur. If you have enough of all three deployed in the correct proportions, you can generally carry the day. So how could the staff of a resource-restricted, government-operated, conservation-driven institution face down a large multinational company aiming to put an open pit gold mining operation in the UNESCO-certified natural area that they are charged with protecting? If you’re the employees of CONANP (The National Commission of Natural Protected Areas) in Baja California Sur you look to the earth. You invoke the powerful forces of nature. You call in the botanists.

When the CONANP team first met Dr. Sula Vanderplank of the Botanical

Sierra El Taste.Photo by Jon Rebman

Research Institute of Texas in 2014, she and her colleague Dr. Benjamin Wilder of the University of Arizona and Next Generation Sonoran Desert Researchers (N-Gen; www.nextgensd.com) had just completed a terrestrial biodiversity study of the lands surrounding Cabo Pulmo National Marine Park. Not coincidentally, these were the same lands targeted by a developer with plans to construct a massive 30,000-room hotel complex on the shores of the marine park. While there are likely many factors that ultimately lead to the termination of the project –massive protests, focused effort by leading local and international NGOs, international media scrutiny – it is beyond a shadow of a doubt that the findings of the team lead by Sula and Ben were a strong contributing factor. Why? In the area where they were to construct the hotel the botanists and their bi-national, multi-disciplinary team recorded no fewer than 560 species of flora and fauna. Of those, 100 (almost 1 in 5) are endemic to the Cape region of Baja California Sur, and 42 are on the Mexican endangered species list. Until that time, no one had any idea of the magnitude of the biodiversity of the area. As the authors of the study concluded, “Given the large number of endemic species present in the area, large-scale development projects risk the full scale and local extinctions of endemic species with narrow geographic ranges. Entire species could be lost forever (and their roles within the Sonoran Desert ecosystem) from the unique places where they evolved in situ during thousands or millions of years.”

Development ‘s deadly impact on biodiversity: CONANP was inspired. Gold mines operating in a protected natural area: N-Gen was invigorated. The opportunity to bring serious scientific scrutiny to Arroyo La Junta and the Los Cardones open pit gold mining project: it was too compelling to ignore. The CONANP/N-Gen team of Sierra scientific superheroes was born.

Now fictional superheroes like Bruce Wayne and Tony Stark conveniently come with immense family fortunes to back their earth-saving endeavors. Not so with reality-bound botanists and their colleagues. When Sula and Ben were first introduced to the Arroyo La Junta area in the Sierra foothills where the Mexican government had authorized the Los Cardones mining project, they couldn’t find much science on the area. A good bit of work had been done at the higher elevations of the Sierras, but the area around the proposed gold mine had remained a generally science-free zone. With the help of CONANP, Sula and Ben set out to change that and, as they had done in Cabo Pulmo, created a proposal to bring rigorous scientific investigation and analysis to determine the magnitude of endemism and biodiversity in the area. CONANP was thrilled. Potential funders were silent.

Anti-mine protest in Todos Santos town plaza. Photo by Kamal Schramm

“Then an interesting thing happened” says Ben. “When the government approved the MIA (environmental impact assessment) of the Los Cardones mine, the people of Todos Santos and La Paz rose up in protest and staged rallies and marches against the mine. This public outcry really gave new life to the importance of understanding the potential impact to the biosphere reserve.”

Anne McEnany, president of the International Community Foundation, had been involved in educating people about economic activities in the Biosphere Reserve for years, and immediately grasped the importance of the N-Gen project. “ICF has been working with local organizations to educate and inform the general public about the Biosphere Reserve and the La Paz watershed by developing curriculum, analyzing potential economic activities, and convening workshops. When the N-Gen research team approached ICF to finance a biodiversity assessment there, we knew it was the right next step. How can CONANP appropriately manage such a large area without knowing what is there?” The CONANP team breathed a sigh of relief. The botanists got busy.

Sula came down in September 2015 to scout out the area and to work with the director of the Sierra La Laguna Biopshere Reserve, Jesús Quiñónez Gómez, on the permitting required for the team to conduct its research. The scouting trip a little scary. Recalls Sula, “The Los Cardones people had guards and check points at several spots in the Arroyo La Junta area, and it was definitely a little intimidating. So when we came back with the whole team in December 2015, we were apprehensive about the type of reception we might receive.” The “whole team” consisted of 46 participants, including 29 scientists from 19 institutions (10 from Mexico and 9 from the US). Everyone was a little nervous, but by the time the team arrived to conduct their 8 days of investigation starting on December 4, 2015, the roadblocks and guards had been removed and the team worked without interference.

And apparently without much sleep either! The group, many of whom had worked on the Cabo Pulmo study and are part of the N-Gen network of investigators, consisted of 5 main teams of scientists: 4 botanists (the plant people), 6 entomologists (the insect folks), 8 herpetologists (the snake and lizard researchers), 7 mammologists (self-evident) and 4 ornithologists (the birders). Specialists for each taxonomic group worked almost around the clock, systematically surveying different areas as daytime collections gave way

Herpetology Team. Photo by Alan Harper

to nocturnal studies, which in turn rolled into bird surveys underway well before dawn. A CONANP management team of 10 people kept the whole project going, while the Rancho Agua de Enmedio family kept them all well fed, and Niparajá assisted with local logistics.

It couldn’t have been more perfect: a CONANP-inspired, ICF-funded, N-Gen-executed project with a multinational team of scientific rock stars to assess the biodiversity of an area that has been consigned to the ravages of open pit gold mining. It is the people of Baja California Sur’s dream team, and if ever salvation were at hand, it is now. But “now” is December. The rains of summer are but a distant memory so few annual plants persist, and the perennials are not sporting many of their distinguishing flowers and fruits; the botanists are challenged. The weather is cool and the cold-blooded snakes are not inclined to come out; the herpetologists find solace in the amphibians. There’s water in the arroyo so land mammals are around, but volant mammals (AKA bats) are the least likely to be active in the Sierras in December; the mammologists scan the night skies with few catches. Aquatic invertebrate communities often show great seasonal variability, and there are substantial taxonomic limitations to larval identification; the entomologists take pleasure in the huge number of harvestman spiders around that freak out all the other scientists. Lots of birds are in residence, but several important species frequent the Cape Region only in summer; the ornithologists make do with what they have.

Baja California Sur Tree Frogs. Photo by Michael Bogan

All of which makes it even more impressive that in the 500 hectares (1,235 acres) of land currently petitioned for use as the Los Cardones open pit gold mine project, the N-Gen team found 877 (eight hundred and seventy-seven!) species of flora and fauna, including 107 species endemic to the Cape Region alone, and 29 species listed as endangered by the Mexican government. Not only that, entirely new species were documented, including 2 insect species (and possibly more), and a completely new plant species record for the entire Peninsula, Brickellia diffusa, part of the sunflower family. And given the limitations of their research – they only had 8 days at a relatively unproductive time of year – the results are all the more astounding. In fact, the scientists reckon that their study represents only 25% (invertebrates) to about 50% (reptiles and amphibians) of the total species present in the region. It’s the frickin’ Garden of Eden on a 500 hectare lot.

But everyone knows that the Garden of Eden comes with a fast-talking serpent (apologies herpetologists) who doesn’t have the happiness of mankind at heart when he offers temptation to the innocent. As Exequiel Ezcurra, Director of the California Institute for Mexico and the United States (UC MEXUS) and co-editor of the study writes in the introduction to the soon-to-be-published study, “At the end of ten years of operations, the Los Cardones mine would have extracted about 173 million tons of rock, 135 million of which will have been deposited as waste in large pilings, and 38 million tons will have been accumulated in tailings in the form of sediments saturated with cyanide solution. In those ten years the project would have consumed about 300 million kilowatt-hours from the local power grid, releasing about 150,000 tons of CO2 into the atmosphere generated by the consumption of about 100 million liters of fossil fuels. In return, the project would generate only about 200 jobs for the entire region and only a meager eight tons of gold for the benefit of a private company.”

Scarier still, like the Garden of Eden, Arroyo La Junta is bounded by rivers, and its tributaries lie along the division of two watersheds. The ridge just to the north of Arroyo La Junta demarcates the boundary where water flows to the La Paz watershed, ending in the Gulf of California. Arroyo La Junta itself flows towards Todos Santos and empties into the Pacific Ocean. As Exequiel writes, “The mining project Los Cardones….plans to extract gold at the headwaters of the La Paz watershed treating the extracted rock with tons of cyanide, an amount sufficient to kill the entire population of Mexico.” Everyone on the peninsula knows that just one big hurricane could release a disaster of untold proportions from the mining site – it’s already happened in Sonora.

Of course it is the water that is the very source of the incredible biodiversity of Arroyo La Junta. The aquatic organisms that the water supports attract a vast array of predators like bats, birds and spiders, and the huge number of insects attracts reptiles and amphibians like frogs, who in turn attract larger predators like raccoons and coyotes. The arroyo is not just a source of drinking water for many of these species, it forms the actual basis for regional biodiversity. The humid air and damp areas extend the active period for many species, most especially reptiles, which means that they can extend their ecosystem functions for a larger part of the year.

CONANP discussed the study’s results. “When a company arrives to undertake a project in a protected area, the government wants to know if the project is compatible with the

Dr. Benjamin Wilder and Dr. Sula Vanderplank at Arroyo la Junta. Photo by Alan Harper

mission of that area. In this case, the protected area is the Sierra La Laguna Biosphere Reserve, and the mission of CONANP is to protect its biodiversity for future generations. The results of this study reaffirm that mining is incompatible with that mission. The mining company says that it can restore everything as it was after it digs these huge holes in the earth, but this study proves that restoration would be extremely difficult, if not impossible.” Ben is more direct. “The biodiversity numbers of the mining company’s MIA (environmental impact assessment) don’t even come close to what we documented. Restoration to what we see today after 10 years of mining would be impossible.” Exequiel agrees. “…we want to remind ourselves again, extinction is forever; our children will never be able to see the species that our generation pushes to oblivion.”

Lawyers, guns and money. In some cases these tools bring clarity, but in others they are employed to obfuscate, intimidate and renumerate away obstacles. And therein lies the beauty of the N-Gen study – it is pure, crystal clear, science. Every fact fully documented and not subject to dispute. And the timing could not be better as there is now a precedent for scientific institutions setting environmental parameters for mining operations. On February 8, 2016 Colombia’s Constitutional Court repealed Article 51 of the National Development Plan that had allowed the Environmental Licensing Authority to authorize mining projects in the Andean paramos, tropical alpine ecosystems. It ordered the Ministry of the Environment to use the map created by a scientific research institute, the Alexander von Humboldt Institute, as the basis for demarcating the boundaries of the paramo habitat. As Exequiel writes, “This was the first time a country had so explicitly put the human right to a safe water supply above the interest of big mining companies. It was also the first time that a nation had given such importance to a scientific research institute in the decision making process.”

Arroyo La Junta is in the part of the Sierras that was designated a Biosphere Reserve by the Mexican government in 1994 and by UNESCO in 2003. So the area’s value has long been suspected, but now, because of the inspiration of the CONANP team to bring in the scientific star power that is the N-Gen network, the true natural wealth of the area has finally been documented and all the players know exactly what is at stake: “Hundreds of species, many of them rare and endemic, others new to science or yet to be described.” The incredibly high rate of endemism is a result of the extreme isolation that the Sierras enjoyed for possibly millions of years. It is the natural heritage of the Mexican nation, and the very source of life for the residents of the Baja California peninsula. All the gold, all the lawyers and all the guns in the world cannot replace it. The botanists showed us that.

Study Findings:

| Group |

No. Taxa |

Endemics |

NOM-059

Endangered Species List |

| Plants |

381 |

77 |

2 |

| Insects |

366 |

15 |

0 |

| Reptiles & Amphibians |

24 |

6 |

16 |

| Mammals |

29 |

3 |

2 |

| Birds |

77 |

6 |

9 |

| TOTAL |

877 |

107 |

29 |

Participating Institutions:

| Mexican Institutions |

US Institutions |

| @Lab |

Botanical Research Institute of Texas |

| CIBNOR |

Next Generation Sonoran Desert Researchers |

| CICESE |

Orma J. Smith Museum of Natural History, The College of Idaho |

| CICESE, Unidad La Paz |

San Diego Natural History Museum |

| CONANP |

San Diego State University |

| Fauna del Noroeste |

San Diego Zoo Global |

| Niparja |

Sky Island Alliance |

| Rancho Agua de En medio |

University of Arizona |

| Terra Peninsular |

University of California, Santa Cruz |

| University of Guadalajara |

|

Vanderplank S, BT Wilder, E Ezcurra. 2016. Arroyo la Junta: Una joya de biodiversidad en la Reserva de la Biosfera Sierra La Laguna / A biodiversity jewel in the Sierra La Laguna Biosphere Reserve. Botanical Research Institute of Texas, Next Generation Sonoran Desert Researchers, and UC MEXUS. 159 pg.

The study will be published in June 2016, and you will be able to find it on the N-Gen web site at www.nextgensd.com.

Todos Santos Eco Adventures operates trekking and cultural programs in the Sierra La Laguna Biosphere Reserve, working with local ranchers and their families. For more information please visit www.TOSEA.net

© Copyright Sergio and Bryan Jauregui, Casa Payaso S de RL de CV, 2016