by Sonya Bradley | Active Adventures, Adventure, Arts & Culture, Blog, Conservation, Culture, Education, Food, Geology, History, Our Properties, Places, Plants, Ranchero Culture, Relax, Sports, Whales, Wildlife, Wildlife Encounters

As a traveler, you have the unique opportunity to enjoy unforgettable experiences while making a positive impact on the world. Sometimes the question is just, “how?”

As a traveler, you have the unique opportunity to enjoy unforgettable experiences while making a positive impact on the world. Sometimes the question is just, “how?”

That’s where Tourism Cares’ Meaningful Travel Map comes in!

We are thrilled to have partnered with Tourism Cares to be among the incredible organizations included on the map. This dynamic tool includes more than 350 vetted, sustainable travel organizations from around the globe — highlighting tours, activities, and businesses that offer a unique, authentic experience while prioritizing environmental stewardship, cultural preservation, and community benefit.

The following are just a few reasons to consider the map before making travel plans:

Enriching Travel Experiences: The Map provides a list of authentic, immersive experiences that go beyond traditional tourism offerings, which allows you to connect deeply with the places you visit and increase overall enjoyment.

Future of Travel: Sustainable tourism is more than a trend — it’s the future of travel. Today, travelers are increasingly seeking meaningful options that align with their values.

Protecting the Industry’s Future: Help make a difference by supporting businesses that protect natural resources, honor local cultures, and give back to communities — our destinations need AND deserve it.

Check Out The Map!

by Sonya Bradley | Active Adventures, Adventure, Arts & Culture, Blog, Conservation, Culture, Education, Food, Geology, History, Our Properties, Places, Plants, Ranchero Culture, Relax, Sports, Whales, Wildlife, Wildlife Encounters

WOW! We are so thrilled with the recent feedback we’ve had from guests and we’re excited to share some of it here. Read on to see what folks are saying or check out our instagram page! Spoiler Alert: Our guides, chefs and support staff are at the heart of everything we do and we couldn’t be more proud of our entire Todos Santos Eco Adventures family! Click here to read more about us.

“We have been all over the world with all kinds of companies, and this one is and always will be

one of our most favorite and cherished trips! We had the most amazing and unforgettable time

at Camp Cecil. What a fantastic operation and experience! Paulina was an exceptional guide, all

of the staff were so kind, friendly, helpful, accommodating, and fun to be around. The food was

unbelievably fantastic (we couldn’t believe how creative and delicious every single thing we ate

was and what the staff were able to come up with in a remote camp). The tents were fantastic,

the bathrooms were super nice, and of course the experiences we had were the absolute best.

Literally everything was perfect and I was so impressed with every single step of the

experience.” Maria B. Nov 2023

“Our guide Octavio was superb in every aspect! He is easily one of the top 5 guides we’ve ever

had anywhere in the world.” Erin M. March 2024

“I want to share with you that you really do have the best guides working with you at TOSEA.

Our excursions and activities were wonderful, and I really have to give an extra special thank

you to Guide Hugo and boat Captain Omar. What an incredible duo. They work so seamlessly

together. Omar is wonderfully passionate and dedicated to providing an incredible experience

on his panga and Hugo is quite possibly one of the best guides I have ever had anywhere in the

world. We just don’t quite have the words for how special they made the visit to the

island.” Kelly C., Jan 2024

“Thank you and your team again for a brilliant and enriching experience. Axel & Bernardo were

exceptional guides in their consummate professionalism, passion for the natural world and

unruffled patience.” Mia C. March 2024

“Our guide, Axel, was simply the best! So knowledgeable about everything in the sea, on land,

and in the air. And his kind, fun, and friendly demeanor made our days. Probably our favorite

part was the 3 nights at Camp Cecil on Isla Espíritu Santo. The snorkeling, kayaking, turtles,

manta rays, sea lions, bioluminescence, hikes…really everything about it was fantastic. We

were especially impressed with the delicious meals that Ricardo and team prepared on a 4-

burner stove in a tent!” Penny F. Jan 2024

“Don’t know how they do it, but every meal exceeded my expectations! They even cooked a

special meal for me since I don’t like fish, which I really appreciated!” Diana W. Feb 2024

“Our guide, Manuel, was superb. We have taken many guided trip and he ranks at the top:

knowledgeable, lively, kind, funny, flexible and able to “read” a group.” Josh O., Dec 2023.

“Martin, our chef at the Sierra Camp, was amazing and that was some of the best food we have

had anywhere.” Bev W., Feb 2024

“Hugo is smart, mellow, accommodating, knowledgeable, energetic, enthusiastic, spiritual and

caring. His knowledge of the history, culture, plants, animals and other aspects of the peninsula

is tremendous. He has a perfect demeanor for handling a group.” Jack S. Jan 2024

“Axel is a fantastic guide. 10/10. Gracious, accommodating, friendly and knowledgeable. I’ll

request him again if I go on this trip again.” John J. Jan 2024

“The guides were amazing. The food was amazing. I can’t really choose my favorite activity –

snorkeling with whale sharks, snorkeling with sea lions, the cooking class. It was all a lot of fun.”

Shelley J. Feb 2024

“I have traveled for many years and I think this trip connected all the activities in a unique way.

The trip was truly outstanding on every level. Sebastian was a fantastic guide, both very

knowledgeable and tuned in to our needs.” Jeff C., Feb 2024

“Our guide Sergio N. did an amazing job with our family of 8, orchestrating everyone’s interests

and activity level at all times, from the young teens up to an 80-year-old. His knowledge of the

land and sea, and his sharing of so many little secrets opened up the island to us and made it so

special. My heart wants to return back sometime soon.” Mark S. Dec 2023

“The food at Camp Cecil de la Isla was some of the best I have ever eaten-SUPER FANTASTIC!

HIGH compliments to Chef Ricardo and full respect for what he was able to do and provide in

such a tiny kitchen space! The menu was creative and fun and the presentation of the food was

FABULOUS. So many small details and I appreciated every little thought and action put toward

the food, camp, and our guides/crew. Our overall experiences will be forever in our hearts,

minds, and souls.” Tanya T. Dec 2023

“Our guides, especially Andrea, were excellent and I have only the highest praise for them.

Andrea was knowledgeable, clear and patient. I also want to say that our boat captains were

the unsung heroes of our trip. We always felt safe and they certainly know how to approach

wildlife safely. Kudos to them all and five stars all around.” Bev W., Feb 2024

“Absolutely incredible experience! Amazing guides, excellent activities, incredibly well-

organized, and fun. From booking the trip until we said ‘hasta luego’ to our wonderful guide,

we had a ball, ate well and learned a lot about the Baja peninsula. Can I give more than 5

stars??” Dianne Z, Jan 2024

by Sonya Bradley | All Media, Blog, Media

Where to stay around Baja California Sur

In Todos Santos: Los Colibris Casitas

Led by a husband-and-wife team pioneering sustainability efforts in Baja California Sur, the carbon-neutral Los Colibris Casitas is a haven for nature lovers and one of the most charming places to stay in Todos Santos. The privileged hilltop location has casitas in lush gardens, with excellent views of the Pacific and a neighboring palm grove. Rates start around $135 per night.

What to do in Baja California Sur

Go whale or bird watching

One of the most magical features of Baja California Sur in Mexico is its rich biodiversity, both on land and in the water.

Between January and March, you can watch giant gray whales in the Pacific Ocean as they migrate south along the western coast of the Baja Peninsula. Trips leave from Todos Santos (about 45 minutes from Cabo) or La Paz, in which case your tour company will drive you across the peninsula.

Year-round, you can go bird-watching to meet frigate birds, roadrunners, kingfishers, hummingbirds, and more. It’s a good way to learn what names to put to the melodic beauties likely to serenade you in the mornings and lull you to sleep each evening.

Both these adventures are available through Todos Santos Eco Adventures, which operates trips leaving from Todos Santos. It’s a carbon-neutral tour company pioneering sustainable tourism in the region.

Booking through companies that think about their environmental impact, practice Leave No Trace principles, and use guides certified by NOLS is one of the best ways to protect the natural beauty of Baja California Sur, Mexico, and preserve it for the future.

Read the full article for inspiration here!

by Bryan Jáuregui | Adventure, Blog, Education, Wildlife

by Bryan Jáuregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures

If science had all the answers, poets and dreamers would be out of a job. So when scientists tell us that they’re not really sure why humpback males sing – and it is only the males that sing – then it’s up to the rest of us to look at the evidence and help science along. And here’s what the evidence shows us. Like traditional mariachis, all-male college a capela groups, and the Rat Pack, humpback whales in Baja clearly understand that singing, particularly with the harmonious help of your mates, is the best way to get the girl. Now some scientists theorize that humpback males are singing only as a type of echolocation exercise of the type used by their dolphin cousins, a way to map out the world around them. This certainly

Humpback Happiness. Photo by Erika Peterman

may be true – because how else are they going to find the girls? But that really doesn’t explain why some humpback whale songs are several hours long and, according to the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, grammatically complex and loaded with information. Like a ballad. Or why sexually immature young males join their virile older brothers in song. Like frat boys with their pledges beneath a sorority girl’s window. Or why all the males in one region will congregate in an arena and sing the same song. Like a boy-band in an outdoor stadium. Or why a male escorting a female and her calf will sing. Like a lullaby. These are all great mysteries that the poets are currently best equipped to ponder, but they don’t begin to touch on the greatest mystery of all – how does the female humpback decide which singer is worthy of her affections? Science presently has no answer, but maybe this is why Elvis always sang alone.

This article was originally published in Janice Kinne’s Journal del Pacifico

© Copyright Sergio and Bryan Jáuregui, Casa Payaso S de RL de CV, 2014

by Bryan Jáuregui | Adventure, Blog, Culture, Travel Industry, Wildlife

by Sergio and Bryan Jáuregui, Todos Santos Eco Adventures

This story was originally published in Janice Kinne’s Journal del Pacifico.

Charles Scammons is the whaler cum naturalist who hunted the gray whales of Baja’s lagoons nearly to extinction in the 1850s and ‘60s. Stories from that time abound of the lagoons running red with the blood of the slaughtered mammals, and of mother gray whales attacking boats in a futile effort to protect their young. Scammons later regretted his slaughter of the whales and, partly as tribute to them, wrote a book that is now considered a classic, The Marine Mammals of the North-western Coast of North America.

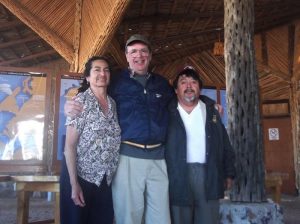

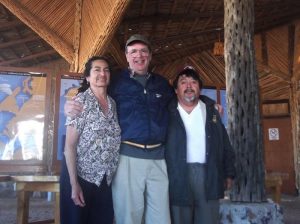

Chris Scammons with Mario and Sara in Guerrero Negro during his 2011 visit.

But guilt continued in the Scammons’ bloodline and in 2011 a great, great grandson of Charles Scammons came to Laguna Ojo de Liebre, or what foreigners call Scammons Lagoon, to apologize to the now-protected whales. Eye witness accounts indicate that four pairs of mother and baby gray whales surrounded his boat and, as he apologized for the actions of his ancestor, the whales stayed with him for an hour, exuding forgiveness and grace. The younger Scammons returned home, filled with the peace he had long sought.

The story of Chris Scammons visit was relayed to us by Rebeca Kobelkowsky, the former director of the Vizcaino Biosphere Reserve and current Ph.D. student at UABCS. We thank her for the story and also for so graciously allowing us to use this photo.

© Copyright Sergio and Bryan Jauregui, Casa Payaso S de RL de CV, 2013

As a traveler, you have the unique opportunity to enjoy unforgettable experiences while making a positive impact on the world. Sometimes the question is just, “how?”

As a traveler, you have the unique opportunity to enjoy unforgettable experiences while making a positive impact on the world. Sometimes the question is just, “how?”